National Education Policy 2020: 5 years later snail pace implementation

The euphoria of the BJP/NDA government at the Centre and Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan about the smooth roll out of the NEP 2020 is not shared by dons of academia and teachers in the country’s 1.4 million schools writes Dilip Thakore & Summiya Yasmeen

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, promulgated after an interregnum of 34 years, crossed the milestone of five years on July 29. The outcome of mountains of labour of the high-powered T.S.R. Subramanian (2016) and Dr. K. Kasturirangan (2018-19) committees, NEP 2020 mandates comprehensive reform of Indian education from pre-primary to Ph D.

Among its major statements of official intent are accordance of high importance to early childhood education; replacing memory-based rote learning pedagogies in K-12 education with development of children’s critical thinking capabilities; integrating hitherto neglected vocational and skills training into secondary and higher education; increasing the duration of undergrad degree programmes from three to four years; establishing an online Academic Bank of Credits (ABC) to enable students to exit and re-enter higher education institutions (HEIs); and introducing research and innovation culture in HEIs.

At a grand fifth anniversary event — the Akhil Bhartiya Shiksha Samagam 2025 (‘All India Education Congress’) — staged in the national capital on July 29, Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan hailed NEP 2020 as “the most crucial pathway to Viksit Bharat”. “Under PM’s leadership, education is not just policy but the greatest national investment. Where there is learning, there is progress. A billion minds unshackled and empowered aren’t just a demographic divided, but New India’s supernova,” wrote Pradhan in an op-ed essay in Times of India (July 29).

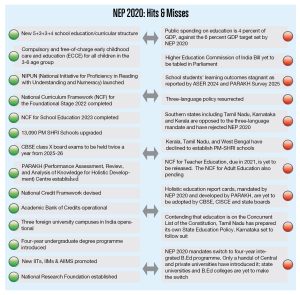

Earlier in May, to mark BJP-led NDA government’s completion of 11 years in office, a Press Information Bureau-published booklet titled Viksit Bharat ka Amrit Kaal-11 Saal (‘11 Years towards Viksit Bharat’) had also enumerated the successful outcomes of NEP 2020. Among them: early childhood education is now compulsory for all children from three years of age under the new reconfigured 5+3+3+4 school education system and integrated with primary education; primary school enrolment has increased to almost 100 percent; inter-disciplinary learning and the four-year degree have become a reality in higher education, and youth employability has been enhanced through skills-based vocational learning programmes.

However, this all-is-well euphoria expressed by the BJP/NDA government and Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan in particular, is not shared by dons of academia and teachers in the country’s 1.4 million schools. Five years on, the shower of programmes/schemes announced to implement NEP 2020 has yet to impact learning outcomes.

The latest Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2024 published by the highly respected Pratham Education Foundation indicates that learning outcomes in India’s rural schools are stagnant. The Union education ministry’s own Performance Assessment, Review, and Analysis of Knowledge for Holistic Development (PARAKH) 2025 survey reports major learning deficits among school students countrywide (see p.50). Likewise, industry reports that the great majority of 10 million graduates annually certified by India’s 52,081 undergrad colleges and 1,338 universities annually are not sufficiently qualified for employment commensurate with their qualifications. Although there is a flurry of activity in the education sector, there is little evidence of reforms-driven forward movement and systemic transformation.

The root cause is that the long-standing promise of all political parties including BJP, to increase the annual outlay (Centre plus states) for education to 6 percent of GDP is nowhere near fulfillment. Since the policy was officially approved in 2020, national public spending on education as a percentage of GDP has inched from 3 to 4 percent per year, way below the 6 percent GDP recommended by the Kothari Commission back in 1967, and the T.S.R. Subramanian (2016) and Kasturirangan (2019) committees. Indeed the K’Rangan Committee — on which NEP 2020 is based — recommends that to make up for lost years, government (Centre plus states) should raise the Centre’s outlay to 10 percent of national expenditure — which would have raised the Centre’s outlay 4.5x to Rs.5 lakh crore in Budget 2025-26.

Moreover, smooth national rollout of NEP 2020 has been derailed by resurrecting the buried ghost of the three-language formula. This ill-advised mandate has reignited passions in several southern states which were up in arms when in 1965 Hindi was declared the national language, and violent protests against “Hindi imperialism” and imposition of this lingua franca of the socio-economically backward northern states countrywide, broke out in peninsular India.

The outcome of this history agnostic mandate of NEP 2020 is that several states of peninsular India including Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala, have rejected the policy in toto. Tamil Nadu has already drawn up its alternative SEP (State Education Policy) arguing that since education is a ‘concurrent’ jurisdiction subject under the Constitution, it is entitled to formulate its own independent SEP. Karnataka and Kerala have followed suit while several other opposition-ruled states including West Bengal and Chhattisgarh are mulling this proposition.

When the Kasturirangan Committee report was made public in 2019, and again when NEP 2020 was officially approved on July 29, in two full-length cover stories in EducationWorld your editors highlighted a major contradiction in the K’Rangan report which was incorporated into NEP 2020. (See https://educationworld.in/ew-july-2019-2/, https://educationworld.in/ew-august-2020/).

On the one hand, the policy mandates establishment of a large number of committees and commissions — HECI, NHERC, GEC, HEGC for higher education and SSSA for school education — to supervise and regulate education from early childhood to postgraduate education. On the other hand, NEP 2020 also mandates “gradual” conferment of autonomy upon all institutions of higher education, to transform into autonomous universities.

The outcome of the education ministry turning a blind eye to this contradiction highlighted by EducationWorld, is that five years on, most of the alphabet soup of committees mandated by the Kasturirangan Committee and faithfully incorporated into NEP 2020, have yet to be constituted — perhaps because the good doctor directed that all appointees should be academics of “unimpeachable integrity”. Simultaneously, there’s been little, if any progress in the direction of conferring autonomy upon HEIs (higher education institutions) by the apex level UGC (University Grants Commission).

For instance in early January, UGC released its UGC (Minimum Qualifications for Appointment and Promotion of Teachers and Academic Staff in Universities and Colleges and Measures for the Maintenance of Standards in Higher Education) Regulations 2025. Under this directive vice chancellors of the country’s 520 state government-funded universities will be appointed by search committees constituted by the state Governor, a political appointee of the Central government. This has provoked a huge outcry in states ruled by opposition parties. Meanwhile the issue of awarding autonomy to St. Stephen’s College — a long-standing demand of the college repeatedly ranked India’s #1 non-autonomous arts, science and commerce undergrad college by EducationWorld — remains in a limbo.

This drift is arousing anger, impatience and indignation within sentient academics in higher education. In a scathing op-edit written for the Chennai-based daily The Hindu (May 14), Bengaluru-based professors Gautam Desiraju and Mirle Surappa of the Indian Institute of Science and National Institute of Advanced Studies respectively, lament the stasis in Indian education five years after NEP 2020 was promulgated and greeted with loud hosannas.

Dr. Kasturirangan, RIP: 484-page draft

“India’s overall graduate employment rate is 42.6 percent, which is practically the same as 44.3 percent in 2023… NEP 2020 is outdated and financially unviable in the India of 2025. With lip service paid to new ideas such as Indian knowledge systems, mother tongue learning, changing history textbooks, flexible curricula (there is) a complete absence of methodology to effect its recommendations. NEP is a dead fish in the water,” they wrote.

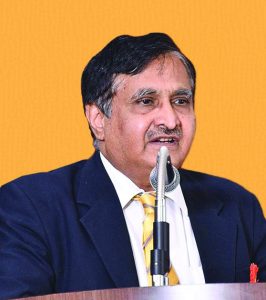

Other educationists tend to be more indulgent. “NEP 2020 is a vision policy, not a legal document. Its implementation requires the Centre and states to enact legislation to implement its mandates. This takes time. I believe that NEP 2020 has done an excellent job of generating awareness and momentum for comprehensive reform across the education spectrum from pre-primary to higher education. For instance,

Singai: not legal document

concepts such as multi-disciplinary education and the academic credits framework which for the first time enables multiple entry and exits in higher education have forcefully impacted educators. Greater political will and higher budget allocations are required to implement NEP 2020 in letter and spirit. Moreover, there’s urgent need to accelerate grant of autonomy to high performing HEIs to fast-forward reforms. Hopefully, on the occasion of the NEP 2020’s fifth anniversary, the government will make greater budgetary provision to implement the liberal provisions of NEP 2020,” says Dr. Chetan Singai, former Chief Consultant, Technical Secretariat of the Union education ministry, that has quickly drawn up the National Curriculum Frameworks for foundational and school education which have been widely acclaimed. Currently, Singai is Dean of Law and Governance at the new-genre private Chanakya University, Bengaluru.

In the pages following, we provide a progress report of NEP 2020 and its impact on early childhood, school, skills and higher education.

Early childhood care & education

Belatedly and mercifully for India’s 65 million children below five years of age, NEP 2020 accords high importance to early childhood care and education (ECCE) — the socio-economic benefits of which have been persistently propagated by your editors.

Since 2010, EducationWorld has convened 12 annual ECCE national conferences and initiated the annual EW India Preschool Rankings to impact the critical importance of professionally administered ECCE provided to pre-primary age children, citing numerous international and national studies indicating that children’s brains are 80 percent developed by age eight. In 2000, Dr. James Heckman, a Nobel Prize winning economist, posited that a dollar spent on professionally provided ECCE saves $16 in the education continuum because children have good foundation.

Accepting this overwhelming body of evidence, NEP 2020 mandates free and compulsory formal ECCE for children in the 3-6 age group by reconfiguration of the centuries-old 10+2 primary-secondary schooling system into a new 5+3+3+4 continuum, formally integrating ECCE into elementary education. NEP 2020 mandates three years of play-based preschool education followed by two years of preparatory classes for all children until age eight.

India’s youngest children are also served by an estimated 60,000 private preschools for children of the middle and elite classes. Over 600 private preschools, some of which are of global standard are annually rated on ten parameters of ECCE excellence by EducationWorld which introduced these rankings in 2010, to impact the value of professionally administered ECCE to children from earliest age upon education policy formulators and parents countrywide.

The annual EWIPR (EducationWorld India Preschool Rankings) have served a useful social purpose inasmuch as enrolling youngest children in formal ECCE institutions has progressed beyond the upper middle to almost the entire middle class comprising an estimated 28 million urban households and the number of private preschools has risen from 15,000 in 2000 to 60,000 currently according to estimates of the Mumbai-based Early Childhood Association of India (estb.2011) which has a membership of 48,000 preschools/educators countrywide.

Anganwadi centre: formidable upgradation challenge

“NEP’s acknowledgement of the critical importance of ECCE and extension of its duration to class III during which all children will joyfully acquire foundational literacy and numeracy — if implemented diligently in the country’s 1.4 million anganwadis and primary schools — could prove to be a game-changer in Indian education. It will build a strong foundation for all future learning. We are jubilant that our long-time advocacy of universal professionally-provided ECCE has paid off,” says Dr. Swati Popat Vats, president of Podar Jumbo Kids, a 452-strong chain of preschools and founding president of the Early Childhood Association of India.

But although sending children in ages 3-5 for pre-primary education in neighbourhood nurseries and playschools has become normative for middle class urban households, parents in poor and socio-economically underprivileged homes are dependent upon low-quality ECCE provided by the 1.39 million Aganawadi Centres (AWCs) established by the Central government in 1976, under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) program and supported by state governments. However since AWCs are essentially nutritional programmes for infants and lactating mothers that also provide early childhood education and care, teaching-learning is minimal with only one ‘worker’ and occasional assistant obliged to provide nutrition and education. Now with NEP 2020 having mandated compulsory formal education for all children in the 3-5 age group, the challenge is to upgrade the quality of education provided to AWC children and accommodate the remainder 50 percent in AWCs and schools countrywide.

To implement NEP mandates in ECCE, in 2021, the government launched the Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 (integrated nutrition support) programme, under which a target to upgrade 200,000 anganwadis over five years (2021-26) was set. However, five years on, according to the Press Information Bureau, as of July 21, 2025, a mere 57,897 out of 200,000 AWCs have been upgraded — an indicator of the government’s snail-paced implementation.

Another promising initiative is the National Initiative for Proficiency in Reading with Understanding and Numeracy (NIPUN) Bharat Mission which has set a target for all children in the three-eight years age group attaining foundational reading and numeracy skills by 2026-27. Five years later, NIPUN Bharat is far behind target. According to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2024, 67.3 percent of class II children cannot read ‘letters’ (alphabet) and 66 percent cannot identify 1-9 numerals. Ditto the widely welcomed first-ever National Curriculum Framework for Foundational Stage (NCF-FS) 2022 has not taken off because of lack of trained teachers to deliver ECCE in AWCs.

A positive fallout of NEP 2020 mandating compulsory ECCE for all children in the 3-6 age group is that several state governments countrywide have added pre-primary/kindergarten sections in government primary schools, formally integrating ECCE in the school education system. This will increase the number of public preschools significantly.

Yet the biggest stumbling block to realisation of NEP 2020’s mandate to universalise ECCE is that the ICDS/NIPUN Bharat schemes have not been followed with sufficient budgetary allocation. The Central government’s allocation for the ICDS programme for the country’s 1.39 million anganwadis is a mere Rs.26,889 crore in 2025-26 — Rs.3,361 per child per year — grossly insufficient to provide adequate nutrition let alone professionally administered early childhood education as envisaged by NEP 2020. Moreover no additional budgetary and policy provision has been made to train and upgrade the skills of the country’s 2.3 million anganwadi workers and helpers to enable them to deliver quality ECCE — an essential mandate of NEP 2020. The overwhelming majority of the country’s 2.3 million anganwadi workers are class X/XII graduates with minimal teacher training in ECCE and are paid a pittance (Rs.8,000-12,000 per month).

Dr. Venita Kaul

“The high importance accorded to ECCE in NEP 2020 has given the sector national visibility and created awareness and discourse about the critical role of foundational stage education. The government has also done well to quickly launch the NIPUN Bharat Mission and NCF-FS 2022. But sadly, the policy’s intent to universalise high-quality ECCE has not been backed up with adequate budgetary allocations. While the policy has tasked the country’s 1.39 million anganwadis to provide quality ECCE, there is no roadmap for building “a cadre of high-quality ECCE teachers in anganwadis” as envisaged by NEP 2020. Most anganwadis are served by a solitary under-paid worker who manages multiple responsibilities — 26 according to some estimates. NEP 2020’s fifth anniversary is an opportune time for government to assess NEP 2020 outcomes in ECCE and recalibrate projects and initiatives, starting with supporting states towards instituting a professionally trained cadre of foundation stage teachers and increasing budgetary outlays for ECCE,” says Dr. Venita Kaul, an alumna of Allahabad University and IIT-Delhi, former education specialist at the World Bank, former professor and founder-director of the Centre for Early Childhood Education and Development at Ambedkar University, Delhi.

Five years on, fulfilling NEP 2020’s mandate to universalise ECCE by 2030 requires the grand Saksham Anganwadi and NIPUN Bharat Mission to be matched with substantially larger budgetary outlays. The Union Budget 2025-26 allocations of Rs.26,889 crore to the ICDS programme and Rs.2,700 crore for NIPUN Bharat are grossly inadequate to upgrade the country’s 1.39 million anganwadis and “build a cadre of high-quality ECCE teachers” to deliver professional ECCE. Five years on, government’s failure to match policy intent with financial commitment to ECCE — a neglected area for over seven decades that is belatedly accorded high importance by NEP 2020 — will have a domino effect and undermine learning outcomes in primary-secondary and higher education in the years ahead.

Primary school students: learning outcomes problem

Primary-Secondary Education

Apart from mandating compulsory professionally administered early childhood care and education (ECCE) which will provide children a strong base for elementary education, in primary-secondary education NEP 2020 mandates a radical and revolutionary pedagogy shift from memorisation and rote learning to experiential learning pedagogies; compulsory vocational education; exam reforms to test children’s conceptual comprehension, creativity and critical thinking capabilities; introduction of continuous formative assessment systems to replace summative exams, and promotion of new digital technologies in school education.

In response to these mandates of NEP 2020, in 2023 the education ministry released the National Curriculum Framework for School Education (NCF-SE), a voluminous 600-page manual which details step-by-step curriculum implementation, providing illustrative learning outcomes for students at every stage — foundational, preparatory, middle and secondary. NCF-SE also dilutes rigid boundaries between the arts, commerce, and science streams to prepare children for multidisciplinary higher education.

To enable school learners to acquire experiential hands-on learning, the Central government has introduced its Atal Tinkering Labs scheme under which the government establishes machines-intensive labs in which children can freely explore, dismantle and reconstitute machines, automobiles, airplane models. Moreover, under a PM Shri Schools programme, the education ministry upgrades existing Central/state government schools with state-of-the-art labs, digital infrastructure and curriculums to stimulate critical thinking, innovation and experiential learning. However, it’s a measure of the BJP/NDA government’s tardy project implementation capabilities that five years on, a mere 8,500 Atal Tinkering Labs have become operational, and 13,090 PM Shri Schools upgraded countrywide.

Five years later, NEP 2020’s school curriculum and pedagogy reforms (and the blindingly detailed NCF-SE) have not translated into improved learning outcomes. According to the latest Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2024 published by the independent Pratham Education Foundation, which field tested 649,491 rural students in the 3-16 age group, 51 percent of class V children cannot read class II texts and 69 percent of class V students can’t solve simple division sums.

Moreover Union education ministry’s own Performance Assessment, Review, and Analysis of Knowledge for Holistic Development (PARAKH) — a national assessment centre established under NEP 2020 mandate — 2025 survey released last month, reports that 45 percent of class III students can’t arrange numbers up to 99 in ascending or descending order; 43 percent of class VI children can’t grasp “main ideas in texts” and a staggering 63 percent of class IX students fail to understand basic numerical sets like fractions and integers. The PARAKH 2025 survey assessed 2.1 million students in classes III, VI and IX in 74,229 schools — government and private — in 781 districts countrywide.

Mehrotra: systemic crisis

According to Prof. Santosh Mehrotra, former professor of economics at India’s show-piece Jawaharlal Nehru University who currently teaches the subject at Bath University (UK), NEP 2020 reforms “don’t address and reflect the ground realities” of India’s school education system. “In NEP 2020 there is no serious recognition of the systemic crisis that unfolded after massification of school education. While enrolment surged, learning levels (outcomes) remained stagnant. The employability crisis in this country is directly related to the education trajectory of the last three decades and yet there is no recognition of this in government. NEP 2020 glosses over foundational issues,” he says.

Moreover, NEP 2020 has unwarrantedly reduced its impact and acceptability by resurrecting the three languages learning formula and mother tongue as medium of instruction from pre-primary to class V, the latter issue settled by the Supreme Court a decade ago. In 2014, the apex court had ruled that parents have a fundamental right to choose the medium of instruction for children in primary education. The three-languages learning mandate has reignited language wars in the country, with the southern states led by Tamil Nadu rejecting NEP 2020 and writing their own SEP (State Education Policy).

Also, the NEP 2020’s tacit approval of government regulation of fees levied by the country’s 450,000 private schools which mentor 110 million children (“the current regulatory regime also has not been able to curb the commercialisation and economic exploitation of parents by many for-profit schools…”) has emboldened state governments to tighten regulatory controls in particular on the issue of school fees (see https://www.educationworld.in/private-school-fees-beware-government-regulation-trojan-horse/).

Undoubtedly, NEP 2020 contains several valuable suggestions and mandates to break with past practices and traditions in primary-secondary education. Yet, if five years after its proclamation there’s little implementation progress and especially improvement in learning outcomes, it’s because the reform mandates of NEP 2020 — switch to new pedagogies, experiential learning, installing digital facilities — require big budgets. This is acknowledged by NEP 2020 which states that “Centre and states will work together to increase public investment in Education sector to reach 6 percent of GDP at the earliest.”

Five years on, government expenditure (Centre plus states) for public education has been stuck in the 2.8-3 percent of GDP rut. Although the NEP 2020 document claims 4.43 percent, the Union government’s own Economic Survey 2023-24 estimates national education outlay at a mere 2.7 percent. The education expenditure outlay of the Centre which should set an example to states has declined from 0.44 percent of GDP in 2023-24 to 0.35 percent in 2025-26.

Mobilisation of resources for investment in developing India’s abundant, high-potential human resource is by no means an intractable problem. For the past ten years coterminously with presentation of the Union Budget, EducationWorld has been presenting a detailed resources mobilisation schema for the Centre to raise Rs.6-8 lakh crore for investment in public preschool to Ph D education.

Although we have invited public critiques of this schema — which has also been sent to several eminent economists for evaluation and debate — there’s no response. Meanwhile despite repeated requests for an interview and constructive dialogue, Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan resolutely declines to interact with your editors.

True, Pradhan has granted interviews to other publications. But it’s respectfully submitted they don’t have equivalent domain knowledge to conduct meaningful solutions-oriented interviews as EducationWorld (estb.1999). Implementation of the constructive and nation-building mandates of NEP 2020 requires ideation and debates rather than issuing ex cathedra statements of intent from Shastri Bhavan, Delhi.

ITI students: width-depth conundrum

Vet/Skills Education

A root cause of contemporary India’s newly laid city roads and national highways quickly pock-marking with potholes; bridges collapsing; numerous railway accidents and civic disasters, is continuous neglect of vocational education in the country’s schools, colleges and universities. Although in the years leading up to India’s independence from British rule in 1947, Mahatma Gandhi recommended that children should learn with head, hearts and hands, his sage advice about learning with hands, i.e, vocational and skills education, was totally ignored. The outcome of continuous neglect of vocational education and training (VET) in Indian education is that only 5 percent of India’s workforce has formal skills training qualifications as against China’s 26 percent, USA’s 50 percent and South Korea’s 96 percent

The ground zero reality that industrially ambitious India needs not only IIT engineers but armies of formally skilled mid-level technicians — road layers, welders, machinists, plumbers, carpenters and construction workers — seems to have completely eluded the country’s central planners who drew up 13 elaborate five-year plans — none of which hit their projected GDP growth targets.

Awareness of the consequences of this prolonged Brahmanical blindspot of India’s centrally planned and heavily regulated primary to Ph D education system began to dawn on leftist central planning proponents and the Planning Commission after India’s post-independence socialist, isolationist economy was liberated and deregulated in 1991, and India Inc started to experience cold winds of competition. New private universities focused on skills development such as AISECT (estb. 2016) and Centurion (2010) started sprouting across the country. Moreover in 2008, the Congress-led UPA government at the Centre promoted the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC), a unique public-India Inc enterprise to augment the VET efforts of the country’s 14,000 ITIs (Industrial Training Institutes) that certify 1.4 million youth per year.

However, the NSDC model under which the corporation funded private sector training institutes to provide VET and skills education failed, because the corporation’s selection of training firms was plagued with scams and scandals. As a result, hasty training and certification of poorly schooled youth failed to produce readily employable workers for industry and especially for labour-intensive MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises) that employ 62 percent of the country’s workforce, and contribute 30 percent of GDP.

In 2014, after establishment of the Union ministry of skill development & entrepreneurship by the newly elected BJP government at the Centre and launch of the Skill India Mission in 2015, NSDC was brought under the new ministry’s purview and revamped. Since then, it has signed up 58,914 reputed private training partner firms and HEIs (including TeamLease, Centurion, AISECT, etc). Its 38 Sector Skill Councils set standards in consultation with industry and draw up curriculums for vocations. According to NSDC, these partnerships have trained 34 million youth for 11,912 job roles.

Evidently NSDC’s claim of having provided VET to 34 million youth is somewhat over-blown. In her budget 2024-25 presentation, Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman said that under the India Skill Mission’s various initiatives including the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), Jan Shikshan Sansthan, National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme, and Craftsmen Training Scheme through ITIs, as of February 2024, the mission had trained 14 million youth, and upskilled and reskilled 5.4 million.

Against the backdrop of India’s youth, population aggregating to 500 million and 10 million graduates streaming out of the country’s 52,081 colleges and 1,338 universities every year, the India Skills Mission’s record of skilling and upskilling 20 million youth is nothing to write home about. India’s 14,000 small Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) certify 1.4 million youth, and 4,600 VET institutes providing short-term PMKVY courses certify an estimated 10 million youth. These figures pale in comparison with neighbouring China whose massive 10,300 secondary school VET institutes and 1,500 VET colleges certify 10 million intensively trained youth per annum.

And it’s pertinent to note that since 1978, when China took the capitalist road and introduced its industrialisation and “open-door” economic reforms, VET has been a strategic pillar of its education system and accorded equal importance with academic education. On the other hand, India gave VET high importance only in 2009 when NSDC was promoted, and again in 2015 under the India Skills Mission. As a result, 24 percent of China’s workforce estimated at 733 million is formally skilled as against a mere 5 percent of India’s 600 million. Little wonder that with its huge number of skilled workers, China recorded compounded annual GDP growth rate of 10 percent for 30 years (1978-2008) consecutively — unprecedented in world history — to increase its GDP to $19 trillion (cf. India’s 4 trillion) and transform into the factory and manufacturing hub of the world.

Although since 2009 and especially since the BJP/NDA coalition was swept to power in 2014, overdue attention has been accorded to VET and an independent ministry of skills development and entrepreneurship established at the Centre, perhaps for historical caste and social reasons, skills training has not yet received the social acceptability that it has in other Asian and developed OECD countries. Moreover, the newly introduced skilling programmes under India Skills Mission tend to be of short-duration, hastily dispensed by edtech firms. As a result, the large majority of skills development programmes dispensed under the PMKVY, Deen Dayal Upadhyay Yojana and other initiatives tend to have width but lack depth.

This is especially problematic because the overwhelming majority of youth who opt for VET typically after classes X and XII have mostly studied in government or rural schools where learning outcomes — as testified year after year by the Annual Status of Education Report — tend to be very poor (53 percent of class VII children can’t read class III texts in their own vernacular languages or manage simple division sums). Therefore, short-duration (three-six month) skilling programmes which usually don’t include industry internships, don’t enthuse industrial firms and employers.

According to a report in the Indian Express (April 4) which quotes skills minister Jayant Chaudhury, between PMKVY 1.0 through PMKVY 3.0 (2015-16 to 2021-22), of the 5.7 million youth certified under short-term training programmes, only 2.4 million (43 percent) have secured employment. Industry associations cite mismatch between course content and industry requirement as the major reason. Since then, under PMKVY 4.0 placement tracking has been discontinued.

Khanna (left): coordination lacuna

Ajay Khanna, Managing Director of Herbalife International India Pvt. Ltd., a subsidiary of the US-based eponymous wellness products megacorp (annual revenue: $4,780 million) and Chairperson of Skills Development at Delhi-based PHDCCI (formerly Punjab, Haryana, Delhi Chamber of Commerce & Industry) which has a membership of 130,000 companies and MSME firms, believes that NEP 2020 provides a useful roadmap. It has charted new direction for Indian education, especially in the realms of early childhood and skills education.

“By according high importance to foundational learning and numeracy, NEP 2020 has generated national awareness that quality primary-secondary education with vocational skills taught right from the start, builds a strong foundation for technical and skilling education. The missing factor in the past has been lack of coordination between vocational training institutes and industry. NEP 2020 rightly urges greater academy-industry collaboration to improve the quality of VET and skilling programmes. For India to experience a VET and skills development revolution, tripartite cooperation between government, industry and training institutes is necessary for curriculum development, internships and experiential learning. In PHDCCI, we have accorded high priority to creating these partnerships and the response from all parties is good. This makes me hopeful that in a short while, a substantially greater percentage of our workforce — especially in MSMEs — will be formally trained,” says Khanna, adding that Herbalife India has formally trained over 700,000 of its independent distributors (sales persons) during the past decade.

Khanna’s observation highlights a major faultline of post-independence India: enduring disconnect between government, academy and industry. Annual national expenditure on research and innovation in 2024-25 aggregated a mere 0.67 percent of GDP cf. 3.8 percent in the US, 2.7 percent in China and 4.9 percent in South Korea. Most of India’s higher education institutions are mere teaching organisations in which R&D activity is perfunctory. This is because after independence under the Soviet-inspired socialist model, the Central government decreed establishment of the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) to conduct breakthrough R&D. But despite establishing 1,000-plus research centres countrywide, CSIR has failed to ideate any global game-changing product, service or disruptive technology.

Wider and deeper cooperation between industry and the academy is the self-evident solution to India’s massive skilled personnel deficit. Although shortage of adequately skilled personnel is the common complaint of every industry leader, industry-academy cooperation has proved a bridge too far. As a result, India Inc has acquired a global reputation for producing cheap shoddy goods and services. Therefore, a renewed effort has to be made to usher in a new era of cooperation between industry and academy, not only in New Delhi and state capitals, but in cities and towns with colleges and universities connecting with local business and industry to shape curriculums, provide internships, and to commission faculty and students to improve and upgrade their products and services.

Dr. A.S. Seetharamu

Dr. A.S. Seetharamu, the erudite former Professor of Education at the Bangalore-based Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) and education advisor to the Karnataka government, is of the opinion that 10-20 percent of the annual expenditure of state governments on subsidisation of government arts, science and commerce (ASC) colleges can be more productively canalised into promoting and upgrading VET institutes and skilling programmes.

“First, there is an urgent need for the Central and state governments through family literacy programmes to disseminate the message that graduates of VET and skills programmes are most likely to earn higher incomes than ASC college graduates. Second, industry and business leaders who constantly complain about shortage of skilled workers and technicians, need to realise that it’s in their own interest to become involved with VET and skilling institutes to design curriculums and provide internship to students. Third, the number of Technical Teacher Training Institutes which are barely a dozen countrywide need to not only be multiplied but be fully equipped to provide AI, IoT, computer-based and online training. And fourth, it’s high time to introduce VET degree programmes to produce professionals with deep training in vocations such as plumbing, electrical wiring, carpentry, machining, roads-building and bridges maintenance. Highly skilled professionals should be incentivised to promote corporate enterprises with large numbers of trained employees. That’s the way to take the India Skills Mission forward,” advises Dr. Seetharamu.

VET trainee: social acceptance problem

Undoubtedly these are valuable and excellent suggestions to develop a skilled and productive national workforce. Yet the elephant in the room issue that neither the Press Information Bureau’s 11 Saal publication, nor Union education minister’s self-congratulatory essay in the Times of India to mark the fifth anniversary of NEP 2020 (July 29, 2020) has touched upon, is increasing rock-bottom budgetary expenditure for realizing the objectives of NEP 2020. None of the skilling mandates of NEP 2020 or the constructive expert suggestions made above can be realized without substantially larger budgetary outlays for the world’s largest child and youth population.

On this metric, the record of the BJP/NDA government at the Centre which provides the lead for states to follow, is dismaying. The annual outlay of the Union Ministry of Skills Development and Entrepreneurship in Budget 2025-26 is a mere Rs. 6,100 crore (capex included). In addition under a new Centre, states and industry programme, Rs.60,000 crore is expected to be spent on upgrading 1,000 ITIs and VET institutes over five years, adding up to a Rs. 16,000 crore per annum. This works out to Rs.762 per capita per year for the country’s 260 million school and 30 million college/university children, all of whom require a modicum of skills education.

It will be a long haul before 25 percent of India’s workforce (equivalent to China) will boast formally acquired skill qualifications.

College students: emigration and multinationals preference

Higher Education

Making higher education more accessible and sharply upgrading teaching-learning and research standards in higher education institutions (HEIs) is a prime focus area of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. The higher education reform proposals of the 66-page NEP 2020 — a remarkable abbreviation of the 484-page Dr. K. Kasturirangan Report researched and written over three years by a committee of nine academics, mainly former chancellors of second string Indian universities, but including Dr. Manjul Bhargava, professor of mathematics at the prestigious Princeton University, USA — starts of with a promising statement. “Regulation of higher education has been too heavy-handed for decades; too much has been attempted to be regulated with too little effect,” says the very first sentence of the policy’s section titled ‘Transforming the Regulatory System of Higher Education’.

However, further on, the policy document contradicts this first statement of intent. NEP 2020 mandates an alphabet soup of regulatory committees to oversee “the distinct functions of regulation, accreditation, funding and academic standard setting” in higher education. Under an “umbrella” Higher Education Commission of India (HECI), the policy proposes regulation of HEIs by NHERC, NAC, HEGC, GEC, NHEQF among other committees.

This is the outcome of the composition of the K’Rangan Committee chaired by the late Dr. Kasturirangan, who served in government organizations including the public sector ISRO (Indian Space Research Organization) through his entire career, and the committee comprising former and serving vice chancellors of government universities. The committee didn’t include any private industry or private Indian university representative as members. Little wonder this cabal of career bureaucrats and government academics has drafted a policy document which heavily monitors and supervises HEIs.

As soon as the Kasturirangan Committee’s draft was published your editors were highly critical of the report (see https://educationworld.in/ew-july-2019-2/) and the NEP 2020 policy document. We highlighted that the elaborate supervisory structure militates against the mandate of institutional autonomy. Somewhat contradictorily and reluctantly, NEP 2020 also proposes “graded accreditation and graded autonomy” for private HEIs “having a philanthropic and public-spirited intent”. Fortunately — perhaps an outcome of EducationWorld’s constructive criticism — five years on none of these regulatory committees have been constituted, and are unlikely to be in the near future.

Indications are that governments at the Centre and in states which are formulating their own SEPs (State Education Policies) will prefer to accelerate NEP 2020’s mandate of gradual conferment of autonomy on HEIs, and disparate colleges to “cluster” into independent and autonomous universities. One hopes that five years on with a large and multiplying number of new genre private universities storming into QS, Times Higher Education and other global rankings league tables, politicians, if not know-all bureaucrats, have learned that academics is best left to academics.

Promisingly, in its self-congratulatory 11 Saal (years) publication to mark the BJP/NDA government’s 11 years in office at the Centre, there is no mention of the numerous higher education regulatory committees recommended by the K’Rangan Committee and dutifully incorporated into NEP 2020.

On the other hand, 11 Saal congratulates the BJP/NDA government for several initiatives it has taken to implement NEP 2020 mandates. Among them: introduction of the four-year undergraduate programme; a national ABC (academic bank of credits) digital repository to facilitate certified multiple exit and re-entry options; phasing out the system of undergrad colleges obliged to affiliate with a parent university, and notification of regulations permitting foreign universities to establish brick-n-mortar campuses in India. Deakin University, Australia inaugurated its campus in GIFT City, Gujarat in early January becoming the first foreign university with a physical campus in India.

11 Saal also takes credit for the number of IITs increasing from 16 in 2014-15 to 23 in 2024-25; IIMs from 13 to 21; AIIMs from seven to 20; establishment of IIT campuses in Abu Dhabi and Zanzibar (Tanzania). Moreover, the document says that India’s rank in the Global Innovations Index has improved from #76 in 2014 to 39 in 2024; the number of Indian universities in the QS World Rankings has increased from 13 in 2014 to 54 in 2025-26, and that the government has promoted a National Forensic Sciences University, sui generis worldwide.

Ex facie, this is an impressive record. However, orderly promotion and dissemination of globally competitive higher education requires attention to detail beyond declarations of intent. Answering a question in Parliament two years ago, Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan admitted that 40 percent of teaching posts in IITs, 31 percent in IIMs and 30 percent in Central universities were vacant. Nor has the situation improved since then. According to a 2025 Parliamentary Committee on education report, of 18,490 sanctioned posts in IITs, NITs, IIMs, and Central universities, 5,418 (29 percent) are unfilled. Alarmingly, 56 percent of professorial positions are vacant.

Low pay, government interference and pathetic government and industry investment in research, drive the best talent abroad. According to a report in Bridge Chronicle (July 6), 35 percent of IIT graduates whose education is heavily subsidised by taxpayers, settle abroad and 60 percent of the remainder work for foreign multinational subsidiaries in India. Low annual rates of economic growth, obdurate red tape slowing industrial growth, pervasive civic mismanagement and difficult ease-of-living conditions are other factors driving Indian talent abroad.

Surappa: full autonomy proponent

Following loud hosannas and acclamation when NEP 2020 was presented to the public five years ago, on deeper reflection well-informed, experienced academics are becoming increasingly disillusioned with the mandates of the policy. According to Dr. Mirle Surappa Founder-Director of IIT-Ropar, former Vice Chancellor of Anna University, Chennai and Dean of Academics at the top-ranked Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, establishment of a plethora of regulatory committees to supervise HEIs is “unwarranted back-seat driving”.

“NEP 2020 mandates too many regulators and regulations for HEIs at a time when they need to be given full autonomy. It decrees too much interference by government which as past experience has shown, hasn’t worked. Policy formulators and the Central and state governments also need to understand that careful supervision and nurturance shouldn’t be restricted to IITs, NITs and IIMs but to the huge number of state government funded HEIs where infrastructure, teaching-learning and research standards are very poor. What the large majority of India’s languishing HEIs need is carefully selected VCs and Directors who should be given full autonomy with accountability. There is rampant corruption, besides casteism playing a dominant role in the appointment of VCs in state universities. There is an imperative for greater funding of state universities which have shown excellence,” says Dr. Surappa.

In this interview with your editor Dr. Surappa has been diplomatic. Earlier in a scathing op-ed essay in the Chennai-based daily, The Hindu (May 14) co-authored by him, he described NEP 2020 as a “dead fish in water” adding that “NEP is outdated and financially unviable in the India of 2025”.

Although NEP 2020 contains several constructive suggestions, including longer duration multidisciplinary collegiate education with flexible entry and re-entry provisions, high importance accorded to university research and innovation and deeper academy-industry cooperation, there’s an emerging consensus that the elaborate government-dominated regulatory super-structure it mandates, needs to be ignored.

Micro-management of HEIs by Central and state government educracies has been tried for seven decades and has failed. None of India’s 1,338 universities, some of 150 years vintage, has innovated a global game-changer product, service or disruptive technology of the import of Meta, Google, Internet or artificial intelligence, even the motorcar or airplane. Therefore, clearly this government control-and-command model needs to be jettisoned in favour of autonomous HEIs managed and driven by highly-qualified and experienced academic leaders and faculty, as indeed somewhat contradictorily mandated by NEP 2020.

Autonomous HEIs led by experienced VCs, Deans and Directors selected transparently by due process, competing for students, faculty and commissioned research offer better prospect of rising to global standards than HEIs strictly regulated by government bureaucrats.

The logic of liberalisation and deregulation of Indian industry and business in 1991 since when the annual GDP growth rate has doubled, needs to be applied to Indian academia. That’s the best way forward to harvest 21st century India’s demographic dividend of the world’s largest youth population.

Add comment