Landmark Education Reforms languid progress (1999-2025)

Twenty six years after EducationWorld was launched on the eve of the new millennium with the ambitious mission statement to propel education to the top of the national development agenda, this objective has not been realised. While the critical importance of QEFA (quality education for all) has impacted the national mindset, education reforms are advancing at glacial pace – Summiya Yasmeen

As on the eve of the French Revolution (1789), post-liberalisation India on the eve of the new millennium was the best of times, and the worst of times, a time of high hopes and winter of despair.

As on the eve of the French Revolution (1789), post-liberalisation India on the eve of the new millennium was the best of times, and the worst of times, a time of high hopes and winter of despair.

In early January 1999, a team of eminent Delhi-based educationists including Anita Rampal, Anuradha De, Prof. Jean Dreze and Dr. Shiva Kumar released the sensational Public Report on Basic Education (PROBE) focused on rural primary education.

For the first time in the history of post-independence India, the report exposed deep rot in public primary education in the populous Hindi heartland states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh). PROBE reported that 48 percent of government schools didn’t have pucca buildings; 53 percent lacked drinking water facility; 89 percent were bereft of toilets; only 3 percent had reliable electricity supply and 33 percent of schools averaged only one teacher because of chronic teacher absenteeism. This unprecedented report also contradicted the popular myth that parents in rural India don’t want to send their children (especially girls) to school. It highlighted that 98 percent of rural parents want boys and 89 percent want girls learning in formal, well-equipped schools.

Outraged and convinced that neglect of education — especially foundational primary school education — and sustained failure to educate its abundant human resource was the main cause of the lowly status of India in the community of nation states worldwide, in November 1999 your editors launched EducationWorld – the Human Development Magazine, with the ambitious mission statement to “build the pressure of public opinion to make education the #1 item on the national agenda”.

Although after 26 years of investing blood, toil, tears and sweat in uninterrupted publication, EducationWorld has established a national reputation as India’s — perhaps Asia’s — #1 education newsmagazine, this ambitious mission statement has not been realised. While the critical importance of QEFA (quality education for all) has impacted the national mindset and education has slowly moved higher on the national development agenda, it’s far from having become the nation’s #1 priority. Nevertheless because of EW’s persistent, unrelenting advocacy, several education legislation policies, schemes and initiatives have been initiated by the all-powerful neta-babu brotherhood to universalise, improve and upgrade preschool, school, higher and skills education.

In 2002, Parliament unanimously enacted the 86th Constitution Amendment to make education a fundamental right of all children (Article 21A). But it took seven years for the State to implement Article 21A by enacting the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, mandating the State to provide free and compulsory education to all children aged between six to 14 years.

In higher education, the Central government enacted the 93rd Constitution Amendment, 2006, enabling the State to decree reservations for socially and educationally backward classes in private educational institutions, including schools. In 2014, after the BJP-led NDA government was voted to power at the Centre, an overdue Skill India Mission was launched to accelerate vocational and skills education. More recently, in July 2020, a new National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 was promulgated after an interregnum of 34 years, based on the recommendations of the K. Kasturirangan Committee. NEP 2020 mandates comprehensive and sweeping reforms of the education system from preschool to university.

Yet, despite much sound and fury and lip service to education reform and your editors’ persistent advocacy for 26 years, as faithfully tracked by the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) of the independent Pratham Education Foundation (estb.1994), there’s been inching progress in the direction of making education the #1 item on the national agenda. According to ASER 2024, 51 percent of class V children in rural India cannot read class II texts and 69 percent of class V students can’t solve simple division or multiplication sums. Likewise, industry reports that the great majority of 10 million graduates certified annually by India’s 52,081 undergrad colleges and 1,338 universities are not sufficiently qualified for employment commensurate with their qualifications.

Nevertheless your editors merit credit for some success in moving the needle of public policy. For instance, our continuous advocacy of the critical importance of professionally administered early childhood care and education (ECCE) — EW convened the first international ECCE Conference in 2010 and several national conventions thereafter and also began ranking India’s best preschools in 2010 — paid off with the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 mandating three years of compulsory ECCE for all children countrywide. Similarly, strident advocacy of investing school and tertiary education students with vocational education and training (VET) has resulted in VET being accorded high importance in NEP 2020.

In a photo-essay in the pages following, we present 11 major landmark initiatives of Indian education of the period 1999-2025. In our opinion they have changed the direction — even if not outcomes — of pre-primary to Ph D education in India.

Supreme Court liberates professional education

In a historic majority judgement in TMA Pai & Ors vs State of Karnataka & Ors delivered in October 2022, a full 11-judge bench of the Supreme Court affirmed the right of private unaided (financially independent) professional education colleges to regulate admissions, determine fee structure and administer their institutions with minimal interference from government. Simultaneously, the apex court not only upheld the right of minorities to “establish and administer educational institutions of their choice” but also expanded this right to all citizens.

In a historic majority judgement in TMA Pai & Ors vs State of Karnataka & Ors delivered in October 2022, a full 11-judge bench of the Supreme Court affirmed the right of private unaided (financially independent) professional education colleges to regulate admissions, determine fee structure and administer their institutions with minimal interference from government. Simultaneously, the apex court not only upheld the right of minorities to “establish and administer educational institutions of their choice” but also expanded this right to all citizens.

However, a year later, in August 2003, in Islamic Academy vs Union of India, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court “clarified” the TMA Pai judgement and whittled down the right conferred upon unaided college managements to determine admissions and fix tuition fees. The apex court decreedestablishment of state-level committees chaired by retired high court judges to determine if admissions are made on merit, and if tuition fees levied are reasonable.

However, a year later, in August 2003, in Islamic Academy vs Union of India, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court “clarified” the TMA Pai judgement and whittled down the right conferred upon unaided college managements to determine admissions and fix tuition fees. The apex court decreedestablishment of state-level committees chaired by retired high court judges to determine if admissions are made on merit, and if tuition fees levied are reasonable.

Subsequently, in August 2005, delivering its verdict in P.A. Inamdar vs. State of Maharashtra, the apex court “clarified” its judgement in the Islamic Academy Case (2003). The court reiterated that Central and state governments have no right to appropriate admission quotas at arbitrary tuition fees in private professional colleges they haven’t funded or financed.

EducationWorld tracked these developments through long-form narratives. See www.educationworld.in Archives (February 2003, September 2003 and October 2005).

86th Constitution Amendment

In December 2002, the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, was unanimously passed by Parliament. It promised enabling legislation to provide universal primary education for all children countrywide. The Act added a new Article 21A to the Constitution, decreeing education a fundamental right of all children between six-14 years of age. However, enabling legislation by way of the Right of Children to Free & Compulsory Education (RTE) Act came seven years later.

In December 2002, the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, was unanimously passed by Parliament. It promised enabling legislation to provide universal primary education for all children countrywide. The Act added a new Article 21A to the Constitution, decreeing education a fundamental right of all children between six-14 years of age. However, enabling legislation by way of the Right of Children to Free & Compulsory Education (RTE) Act came seven years later.

See www.educationworld.in Archives (January 2002)

93rd Constitution Amendment Act, 2005

To nullify the judgement of the Supreme Court in PA Inamdar vs. State of Maharashtra (2005) which reaffirmed that the State cannot impose its quota reservation policies on private unaided colleges, the Union HRD ministry responded with the 104th Constitution Amendment Bill which specifically overruled this unanimous apex court judgement. This Bill became the Constitution 93rd Amendment Act, 2005, when President Abdul Kalam signed it on January 20, 2006. Subsequently, a new cla use was added to Article 15 of the Constitution permitting the State to decree reservations for

To nullify the judgement of the Supreme Court in PA Inamdar vs. State of Maharashtra (2005) which reaffirmed that the State cannot impose its quota reservation policies on private unaided colleges, the Union HRD ministry responded with the 104th Constitution Amendment Bill which specifically overruled this unanimous apex court judgement. This Bill became the Constitution 93rd Amendment Act, 2005, when President Abdul Kalam signed it on January 20, 2006. Subsequently, a new cla use was added to Article 15 of the Constitution permitting the State to decree reservations for  other socially and educationally backward classes (OBCs) in all government and private higher education institutions.

other socially and educationally backward classes (OBCs) in all government and private higher education institutions.

As a result, the validity of the judgement of the Supreme Court in Indira Sawhney vs. Union of India (1992) which capped reservations at 49.5 percent of institutional capacity, became doubtful.

See www.educationworld.in Archives (February 2006)

Nationwide OBC reservation protests

To test the constitutional validity of the 93rd Amendment, on April 5, 2006, Union HRD minister Arjun Singh announced that the coalition UPA-I government at the Centre had approved his ministry’s proposal to reserve an additional 27 percent (in addition to the 22.5 percent reserved quota for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes) of capacity in Central government promoted universities and higher education institutions (JNU, IITs, IIMS, AIIMS, etc) for OBC (other backward castes) students. The student community, particularly in north India, responded to this out-of-the-blue reservation diktat with nationwide protests

To test the constitutional validity of the 93rd Amendment, on April 5, 2006, Union HRD minister Arjun Singh announced that the coalition UPA-I government at the Centre had approved his ministry’s proposal to reserve an additional 27 percent (in addition to the 22.5 percent reserved quota for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes) of capacity in Central government promoted universities and higher education institutions (JNU, IITs, IIMS, AIIMS, etc) for OBC (other backward castes) students. The student community, particularly in north India, responded to this out-of-the-blue reservation diktat with nationwide protests  and campus rioting. Following a huge public furore and media (including EW) criticism, a special government committee recommended expansion of institutional capacity of Central government institutions to avoid reduction of merit students’ quota.

and campus rioting. Following a huge public furore and media (including EW) criticism, a special government committee recommended expansion of institutional capacity of Central government institutions to avoid reduction of merit students’ quota.

The additional 27 percent reservation diktat has intensified competition for admission into the nation’s too-few high-quality institutions for ‘merit’ students, diluted academic standards and generated social tensions in campus India and society.

EW covered this issue with a cover story ‘Reservation shadow over campus India’ (See www.educationworld.in Archives — May 2006)

Right to Education Act, 2009

Over 60 years after the framers of India’s Constitution directed the State to “make effective provision for securing the right to work, to education…” (Article 41), on August 14, 2009, the Lok Sabha unanimously passed the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Bill, 2009 (aka RTE Act). The Act makes it incumbent upon the State to provide free and compulsory education to all children aged between six to 14 years. While the RTE Act was widely welcomed, s.12 (1) (c) of the Act, which mandates all private unaided schools to reserve 25 percent of capacity in class I for children from poor households in their neighbourhood and retain them until class VIII, drew criticism for encouraging “creeping nationalisation” of private schools.

Over 60 years after the framers of India’s Constitution directed the State to “make effective provision for securing the right to work, to education…” (Article 41), on August 14, 2009, the Lok Sabha unanimously passed the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Bill, 2009 (aka RTE Act). The Act makes it incumbent upon the State to provide free and compulsory education to all children aged between six to 14 years. While the RTE Act was widely welcomed, s.12 (1) (c) of the Act, which mandates all private unaided schools to reserve 25 percent of capacity in class I for children from poor households in their neighbourhood and retain them until class VIII, drew criticism for encouraging “creeping nationalisation” of private schools.

The high promise RTE Act which came into force on April 1, 2010, legitimises blatant discrimination against private schools. For instance, s.19 prescribes a wide range of mandatory infrastructure provisions for private schools, but exempts 1.20 million government schools from adhering to them. Moreover, s.12 (2) of the Act, which directs (state) governments to pay private schools the per-child expense incurred by government in its own schools to compensate them for providing free-of-charge education under s.12 (1) (c), has resulted in cash-strapped state governments owing schools thousands of crores. For instance, in Maharashtra, private schools are owed Rs.2,000 crore by way of s.12 (2) reimbursement.

See www.educationworld.in Archives (‘RTE shadow over

India’s most admired schools’ — October 2010)

SC upholds RTE Act, 2009

In a landmark judgement delivered on April 12, 2012 in Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan vs. Union of India & Anr, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the Union government’s Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, and particularly the controversial s.12 (1) (c) — reserving 25 percent capacity for poor neighbourhood children in elementary classes of private schools. But the full impact of reservation was diluted by exempting minority (and boarding) schools. Since then, a large number of private schools have claimed linguistic and/or religious minority status.

In a landmark judgement delivered on April 12, 2012 in Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan vs. Union of India & Anr, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the Union government’s Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, and particularly the controversial s.12 (1) (c) — reserving 25 percent capacity for poor neighbourhood children in elementary classes of private schools. But the full impact of reservation was diluted by exempting minority (and boarding) schools. Since then, a large number of private schools have claimed linguistic and/or religious minority status.

However, while the impact of s.12 (1) (c) has been diluted by exemption of minority schools, this judgement forced open the flood gates for entry of dreaded licence-permit-quota-raj and inspector regime into private K-12 education.

See www.educationworld.in Archives (‘Supreme Court green light for licence-permit-quota-raj in school education’ — May 2012)

SC medium of instruction verdict

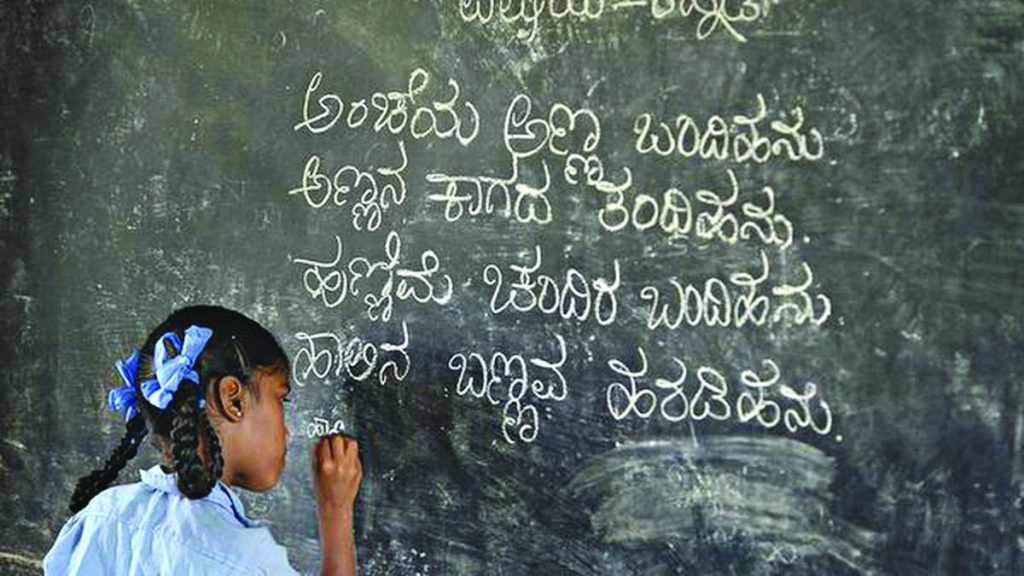

In a landmark judgement delivered on May 6, 2014 in State of Karnataka & Anr. vs. Associated Managements of (Government Recognised Unaided English Medium) Primary & Secondary Schools & Ors, the Supreme Court upheld a 2008 Karnataka high court judgement which had quashed a state government order issued in 1994 mandating Kannada or mother tongue as the compulsory medium of instruction in all primary schools statewide.

In a landmark judgement delivered on May 6, 2014 in State of Karnataka & Anr. vs. Associated Managements of (Government Recognised Unaided English Medium) Primary & Secondary Schools & Ors, the Supreme Court upheld a 2008 Karnataka high court judgement which had quashed a state government order issued in 1994 mandating Kannada or mother tongue as the compulsory medium of instruction in all primary schools statewide.

The apex court ruled that imposing any language as the medium of instruction violates the fundamental right of parents and children to choose their preferred in-school language of instruction.

However this SC verdict has not ended decades of confusion, obfuscation, harassment and corruption aided and abetted by state governments on the issue of regional language or mother tongue being employed as the mandatory language of instruction in primary school. NEP 2020 reiterates that early childhood and primary school children should learn in their mother tongue, ignoring the ground reality that 20 children in a given classroom may have 12 mother tongues.

See www.educationworld.in Archives (Education News report June 2014)

Skill India Mission

On the first-ever World Youth Skills Day (July 15, 2015), the BJP-led NDA government launched the Skill India Mission. A National Skill Development Mission and a new National Policy for Skill Development & Entrepreneurship (NPSDE) 2015 are the main features of the initiative. The Skill India Mission set a target of skilling 400 million people by 2023.

On the first-ever World Youth Skills Day (July 15, 2015), the BJP-led NDA government launched the Skill India Mission. A National Skill Development Mission and a new National Policy for Skill Development & Entrepreneurship (NPSDE) 2015 are the main features of the initiative. The Skill India Mission set a target of skilling 400 million people by 2023.

While the Skill India mission highlighted the critical importance of skilling for national development, progress has been slow. In her budget 2024-25 presentation, Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman said that under the Skill India Mission’s various initiatives including the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), Jan Shikshan Sansthan, National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme, and Craftsmen Training Scheme through ITIs, as of February 2024, the mission had trained 14 million youth, and upskilled and reskilled 5.4 million. That’s 380 million short of the 400 million target.

See www.educationworld.in Archives (‘India awakes to vocational education’ — February 2010, ‘India’s belated skilling revolution’ — April 2014, ‘Skilling reskilling, upskilling fever raging countrywide’ — August 2024)

Prolonged pandemic schools lockdown

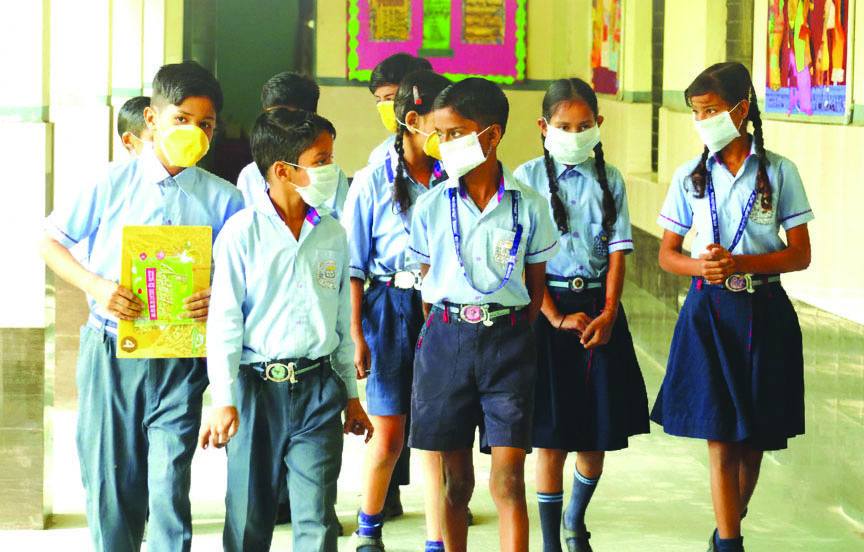

On March 16, 2020 the Union government announced the closure of all schools, colleges and universities across the country to control and check spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. All major examinations, including public entrance exams such as JEE and NEET were postponed and several school-leaving board exams in the states of the Indian Union abandoned midway. This directive was also applied to higher and professional education institutions, which also had to close down campuses and discontinue classes and project work mid-semester. Schools and HEIs were advised to continue teaching-learning in the online mode.

On March 16, 2020 the Union government announced the closure of all schools, colleges and universities across the country to control and check spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. All major examinations, including public entrance exams such as JEE and NEET were postponed and several school-leaving board exams in the states of the Indian Union abandoned midway. This directive was also applied to higher and professional education institutions, which also had to close down campuses and discontinue classes and project work mid-semester. Schools and HEIs were advised to continue teaching-learning in the online mode.

However, this cautionary lockdown transformed into the world’s second longest (after Uganda) education lockdown of 56 weeks resulting in unprecedented learning loss suffered by the world’s largest child and youth population. EducationWorld strongly opposed the unwarranted prolonged lockdown of education institutions. Though schools reopened in late 2021/early 2022, several studies indicate that millions of children are still struggling to regain the learning ground lost during the pandemic lockdown.

See www.educationworld.in Archives (Cover stories: ‘Why schools should reopen now’ (July 2021); ‘Pandemic thunderbolt endangers early years education’ (February 2021); ‘10 Post-pandemic recovery solutions (March 2022))

National Education Policy (NEP) 2020

The much-awaited National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, formulated after an interregnum of 34 years and incorporating most of the detailed recommendations of the K. Kasturirangan Committee, was presented to the public on July 29, 2020. The compact 65-page NEP 2020 mandates three years of compulsory early childhood care and education for all children countrywide in the 3-6 age bracket through reconfiguration of the 10+2 school system with a new 5+3+3+4 school continuum; curriculum, pedagogy and exam reforms in school education to encourage conceptual comprehension, creativity and critical thinking capabilities rather than rote learning; introduction of certified multiple exit and re-entry options in higher education and a system of credits to be stored in a national ABC (academic bank of credits) digital repository; phasing out the system of all undergrad colleges affiliating with parent universities, and graded autonomy for undergrad colleges under a ‘light but tight’ regulatory framework; and permitting top-ranked foreign universities to set up campuses in India. On the flip side, the policy mandates too many regulatory supervisory agencies while promising “light but tight” regulation.

The much-awaited National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, formulated after an interregnum of 34 years and incorporating most of the detailed recommendations of the K. Kasturirangan Committee, was presented to the public on July 29, 2020. The compact 65-page NEP 2020 mandates three years of compulsory early childhood care and education for all children countrywide in the 3-6 age bracket through reconfiguration of the 10+2 school system with a new 5+3+3+4 school continuum; curriculum, pedagogy and exam reforms in school education to encourage conceptual comprehension, creativity and critical thinking capabilities rather than rote learning; introduction of certified multiple exit and re-entry options in higher education and a system of credits to be stored in a national ABC (academic bank of credits) digital repository; phasing out the system of all undergrad colleges affiliating with parent universities, and graded autonomy for undergrad colleges under a ‘light but tight’ regulatory framework; and permitting top-ranked foreign universities to set up campuses in India. On the flip side, the policy mandates too many regulatory supervisory agencies while promising “light but tight” regulation.

Five years after NEP 2020 was approved, policy implementation has been snail-paced. The several supervisory and regulatory committees it mandates including HECI, GEC, NAC, HEGC have not been constituted. While the NCF-FS (National Curriculum Framework for Foundational Stage) 2022 and National Curriculum Framework for School Education (NCF-SE) 2023 have been published, the curriculums for teacher and adult education are pending.

Moreover, smooth national rollout of NEP 2020 has been derailed by resurrecting the buried ghost of the three-language formula. Several states of peninsular India including Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala, have rejected the policy in toto because of its endorsement of the three-language formula and imposition of Hindi. Tamil Nadu has already drawn up its alternative State Education Policy 2025. Most importantly, NEP 2020 implementation has been stymied because of inadequate budgetary allocations — the Central and state governments have conspicuously failed to fulfil the policy’s mandate to increase national education spending to 6 percent of GDP.

EducationWorld has closely tracked the roll out and formulation of NEP 2020 in several unmatched long-form features including a detailed critique of NEP 2020. See www.educationworld.in Archives — Cover stories ‘NEP 2020: Visionary charter, educracy shadow’ (August 2020) & ‘National Education Policy 2020: 5 years later snail-pace implementation’ (August 2025).

Green light for foreign universities

In November 2023, the Delhi-based University Grants Commission (UGC) finally granted permission to well-reputed foreign universities to establish offshore campuses in India — a proposition EW had backed from 2007. The UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) notification provides a legal and regulatory framework for foreign universities to establish owned campuses in India and sets terms and conditions for entry of foreign HEIs. Among them: Applicant foreign universities must be ranked among the Global 500 in league tables approved by UGC from “time to time”; degrees awarded must be on a par with country

In November 2023, the Delhi-based University Grants Commission (UGC) finally granted permission to well-reputed foreign universities to establish offshore campuses in India — a proposition EW had backed from 2007. The UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) notification provides a legal and regulatory framework for foreign universities to establish owned campuses in India and sets terms and conditions for entry of foreign HEIs. Among them: Applicant foreign universities must be ranked among the Global 500 in league tables approved by UGC from “time to time”; degrees awarded must be on a par with country  of origin; tuition fees should be reasonable; faculty employed have to be on a par with country of origin; study programmes should not be contrary to sovereignty of India and should “adhere to public order, decency and morality”.

of origin; tuition fees should be reasonable; faculty employed have to be on a par with country of origin; study programmes should not be contrary to sovereignty of India and should “adhere to public order, decency and morality”.

Consequent upon this formal UGC notification, Deakin University, Australia became the first foreign university to establish a campus in the Gujarat International Finance Tec-City (GIFT City), near Ahmedabad. Currently, three foreign universities have established campuses in India with another 14 granted permission.

See www.educationworld.in Archives (Cover story ‘Time to welcome foreign universities’ — October 2007; Special Report ‘Half-hearted invitation to foreign universities’ — January 2024)

Add comment