No products in the cart.

Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi: Left ideologies alive in India’s most reputed liberal arts university

Over a decade after the BJP swept to power in Delhi and put all its weight behind its student wing — ABVP — Left Unity, an alliance of several leftist students unions affiliated with Left national parties including CPI-M, won a sweeping victory in the latest JNUSU election – Kaveree Bamzai

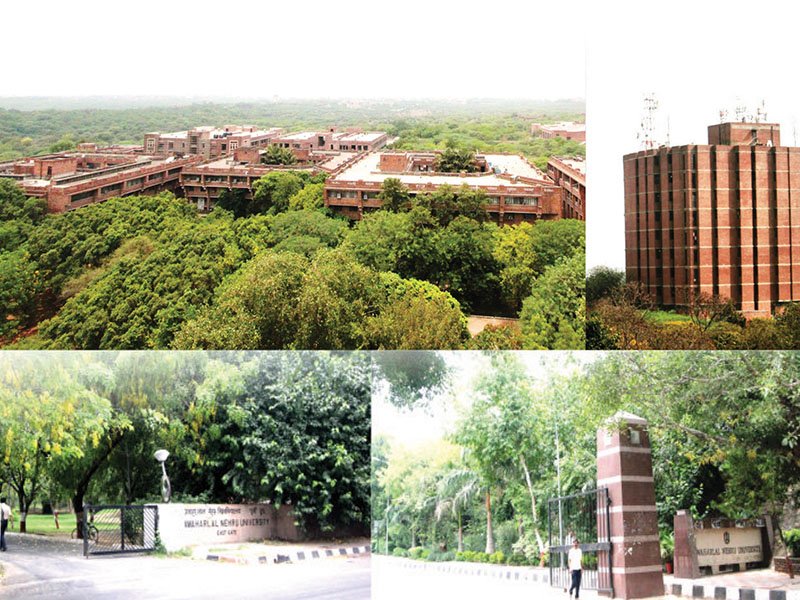

JNU: no expense spared greenfield, globally benchmarked liberal arts & humanities public residential university

Ever since the BJP-led NDA juggernaut led by former three-term Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi was swept to power in New Delhi in General Election 2014, reducing the number of seats in the Lok Sabha held by the Congress to 44 from the 206 it won in General Election 2009, all political parties and media pundits have been predicting the end of Left students unions that have dominated the showpiece postgraduate Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) established in 1969 on a 1,019-acre campus in the heart of Delhi.

However, in the latest JNUSU (Jawaharlal Nehru University Students’ Union) elections, held on November 4 — over a decade after the right-wing revivalist BJP swept to power and put all its weight behind its students wing, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) — Left Unity, an alliance of several leftist students unions including AISA, SFI and DSF affiliated with Left national parties including CPI-M (Communist Party of India-Marxist), won a sweeping victory bagging the offices of President, Vice President, General Secretary and Joint Secretary.

Aditi Mishra: turning tide

In her victory speech, JNUSU’s new President Aditi Mishra interpreted the Left Unity alliance’s thumping win as a wider mandate. She had no hesitation in beginning her speech with the ‘Lal Salaam’ (Red Salute) and castigating the incumbent BJP/NDA government for propagating communalism, religious division with toxic rhetoric against Muslims and practising crony capitalism.

“The victory of the Left Unity alliance in India’s most respected liberal arts postgraduate university is a rejection of the patriarchy and hierarchy norms that ABVP activists are attempting to introduce in JNU to replace the egalitarian and mutually respectful faculty-student interaction. And outside JNU, I am hopeful that public opinion is beginning to turn against the communal and divisive propaganda of the BJP and RSS which is weakening the country. BJP’s huge majority in Parliament was reduced considerably in General Election 2024. I am hopeful that public opinion is turning against BJP/RSS policies of inequality, insecurity, precarity and monopoly capitalism. I believe the victory of Left Unity in JNU is the first sign of the turning tide,” says Mishra.

Dr. Nivedita Menon, who recently retired after a long 17-year innings as professor at JNU’s Centre for Comparative Politics and Political Theory, School of International Studies, concurs: “JNU is respected countrywide for its egalitarian culture which is larger than individuals. The recent JNUSU election result indicates that there is hope among students, that there is still a hunger for ideas and a love for a democratic perspective, that there is still some resistance to the current regime.”

Established in memory of India’s first prime minister 56 years ago, JNU was intended to represent the ideals that Jawaharlal Nehru lived by — secularism and cosmopolitanism, social justice and scientific temper, interest in international affairs and commitment to world peace. Therefore despite the Central government’s strained finances at the time, no expense was spared by the Congress government at the Centre headed by Nehru’s daughter, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to establish JNU as a greenfield globally benchmarked liberal arts and humanities postgrad residential university.

Rather than adapt from colonial-era buildings, the new university’s layout emphasised low-rise academic blocks, pedestrian pathways, and generous open spaces, creating a calm learning ecosystem with large lecture halls and seminar rooms designed for discussion-based learning, while dedicated research spaces for faculty and Ph D scholars provided easy access to audiovisual teaching aids, rare in Indian universities of the 1960s. Its Central Library (later named after Dr. B.R. Ambedkar) sprawled over nine floors, is among the most well-equipped in the country housing over 2 million volumes and 1,600 journal subscriptions. Moreover, apart from rock-bottom tuition fees ranging from Rs.420-5,850 per annum and residential fees of Rs.1,200 per annum in purpose-built hostels for students, and free-of-charge housing for faculty and staff, the university features spacious dining halls offering highly subsidised meals and integrated campus services — health centre, post office, shopping complex. Doctoral scholars who constitute 40 percent of JNU’s 9,000 students are awarded stipends varying from Rs.8,000 (for non-NET) to Rs.35,000 (UGC-JRF) per month.

Yet despite the enabling environment that it provides to students who until 2022-23 were admitted on the basis of performance in the university’s own entrance test (now they are admitted on basis of CUET (Common University Entrance Test) conducted by the Central government’s National Testing Agency), apart from economics Nobel laureate (2019) Dr. Abhijit Banerjee, JNU’s record of producing internationally celebrated alumni over a period of 56 years is somewhat underwhelming. However, it has shaped nationally celebrated scholars (historians Romila Thapar, Ramachandra Guha, sociologist Jean Dreze); political theorist Yogendra Yadav; the late CPM general secretary Sitaram Yechury and incumbent Union finance and foreign affairs ministers Nirmala Sitharaman and S. Jaishankar. Right wing critics of this allegedly “mollycoddled” university say that in terms of cost-benefit ratio this show-piece university (annual grant from the Union Budget: Rs.517.97 crore in 2022-23) hasn’t delivered.

Be that as it may, there is unanimity in this privileged institution of higher learning that after the BJP came to power at the Centre in 2014, it has been labelled a staunch Left bastion. Since then, JNU has been routinely vilified by the media and the government for the “anti-national” character of its students who raised slogans of azadi for Kashmir at a protest in February 2016 and were charged with sedition. One of them, Umar Khalid, has been in Tihar Jail since September 2020, accused of involvement in the Delhi riots and consistently denied bail, except for a week off in 2024 for a family wedding.

VCs Jagadesh Kumar & Santishree Pandit (right): institutional character change charge

After the exit of vice chancellor Sudhir Sopory in 2016, and installation of M. Jagadesh Kumar, and later Santishree Dhulipuli Pandit in 2022, the character of the university has changed. What was once frowned upon is happening routinely. Dozens of RSS swayamsevaks often march across the campus with drums, trumpets, and clashing cymbals, accompanied by ABVP students/activists wielding shakha lathis.

Comments recently elected JNUSU President Aditi Mishra: “You see ISKCON preachers at every corner of JNU selling the Bhagavad Gita. Can you imagine how the administration would react if preachers sell the Bible or the Quran?”

However, JNU Vice Chancellor and alumna Santishree Dhulipuli Pandit sees nothing wrong in the RSS parades, known as path sanchalan being staged on campus. “GenZ seems to be less interested in Left and extreme Left politics. This is the third year there has been a path sanchalan. There is a change and weakening of the Left among faculty and students,” she told EducationWorld.

Certainly, the university has undergone a transformation on three important counts: composition of its students, its faculty and the nature of its academics. Once a bastion of liberal values, where students and teachers engaged in debates, where teachers had a say in how their departments were run, and where teaching-learning was of global standard, JNU is slowly being turned into an institution where decision making lacks transparency, students are being policed, and now the focus is on Indian knowledge systems.

In its annual report published last October, the JNU Teachers’ Association (JNUTA) says: “JNU has suffered terribly under the effects of concerted attacks it has faced since February 2016. The vicious campaign slandering the image of the institution, its faculty, and its students, that was unleashed at that point of time was only the beginning of a long drawn process of sapping the institution of the vital energies that underlay its remarkable achievements and earned the institution such great prestige across the country and the world. What has followed has been a systematic process of undermining the institution from within, with the office of the Vice Chancellor serving as its hotbed.”

Pandit denies these charges. “JNUTA is full of half truths to help their fake narrative. The truth is that JNU is back to research and academics. We’ve had four years of academics and research in a peaceful yet vibrant atmosphere. In April, JNU was awarded the prestigious PAIR (Partnerships for Accelerated Innovation and Research) grant, becoming a Hub institution to mentor other universities in basic sciences,” says Pandit.

The PAIR grant of the Anusandhan National Research Foundation is a major Indian government initiative launched under the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 to boost research in universities by pairing less-resourced institutions with top-tier (Hub) ones for mentorship, fostering collaboration, and transforming India’s research landscape into a vibrant ecosystem for innovation and global leadership.

Protesting students on JNU campus

The outcome of students and faculty being ranged against the JNU administration/management is that this institution which shaped a large number of India’s best scholars, is in danger of losing its liberal credentials. Students from backward and disadvantaged communities are increasingly becoming ineligible for admission owing to the policy of ‘deprivation points’ for admission is endangered owing to JNU no longer conducting its own entrance exam.

Since the academic year 2022-23, admission into postgraduate and the handful of undergraduate courses is dependent on students’ performance in the Common University Entrance Test (CUET) conducted by the National Testing Authority. CUET is in the Multiple Choice Question (MCQ) format and needs to be accessed on a computer. Both these requirements are hurdles for students from disadvantaged communities, who may not be familiar with computers or have no access to them except at cyber cafes; and are unlikely to be accustomed to the MCQ format.

Therefore two years on, there is a clear change in the composition of students admitted, specifically from marginalised communities. The percentage of women students on campus, which had risen to 51.4 percent in 2017-18, has plunged to 43.1 percent in 2024-25. According to a JNUTA report, between 2021-22 and 2024-25, scheduled castes (Dalit) students declined from 1,500 to 1,143, and scheduled tribe (ST) students from 741 to 545. This has reduced the share of the total SC and ST percentage to 21.1 percent (cf. the constitutionally mandated 22.5 percent).

The character of this showpiece national university established as an essentially deep research institution has also changed under the new political dispensation, inasmuch as research students are now outnumbered by students in undergrad and postgraduate programmes.

The count of research scholars has declined from 5,432 in 2016-17 to 3,286 in 2024-25 with their percentage declining from 62.2 percent to 40.1 percent over the past decade. According to JNUTA spokespersons, this is the result of UGC imposing a uniform cap on the number of M.Phil and Ph D students who can be guided by faculty. Whereas 2009 UGC regulations recommended caps on M.Phil and Ph D scholars (e.g, eight Ph D and five M.Phil scholars), in 2016, under Jagadesh Kumar’s watch, the number of scholars supervised by professors, associate professors and assistant professors was capped uniformly for all universities withdrawing the discretion of JNU’s academic council. This placed JNU with its excellent faculty on a par with substantially lower-ranked universities resulting in a drop in M.Phil and Ph D scholars in JNU. Between 2015-16 and 2021-22, JNU’s total research expenditure dropped from Rs.30.28 crore to Rs.12.78 crore, a 57.8 percent decrease. Expenditure on research and student-related activities has been hardest hit.

The steady dilution of this prestigious research university by UGC with acquiescence of the vice chancellor, has dismayed the faculty and JNUTA, which complains that the faculty selection process has also been gamed. Currently, every selection committee has three subject experts, chair of the centre, dean of the department, and a member appointed by the Visitor. The committee is chaired by the Vice Chancellor. But with the heads of centres being chosen by the Vice Chancellor, and the experts being chosen by the Dean, the earlier system of selection by seniority has been compromised.

Mazumdar: compromised selection

“Earlier, the primary consideration was academic and the specificity of the study centre’s requirements. But now JNU’s faculty recruitment process has been undermined. Over 300 faculty members have been appointed during the tenure of Jagadesh Kumar and Pandit,” says Dr. Surajit Mazumdar, an alum of Delhi University and JNU, and currently professor of economics and president of JNUTA.

Sudha Bhattacharya, who quit JNU in 2020, describes the teacher-student relationship with nostalgia. “JNU had a very inclusive atmosphere where students were drawn from varied backgrounds, ideologies, and cultures. In my case, since the students spent a good five-six years in my lab for their Ph D, I developed a very close relationship with most of them. For example, one of my students was the first generation from a farming community reading for a Ph D, another could not converse in any language other than Bangla. Yet another, a Kashmiri Muslim girl student, slowly shed her orthodox inhibitions, and so on. Meeting such students was possible because of JNU’s inclusive admission policies. Apart from my own mentoring, JNU provided them the free atmosphere to grow, become self-confident but not arrogant,” says Bhattacharya, a former professor at the School of Environmental Sciences, and currently a fellow at the National Academy of Sciences, Indian Academy of Sciences, and Indian National Science Academy.

Paranjape: illiberal liberalism rampant

However the left-liberal dominance of JNU is increasingly being challenged in the post 2014 era. “Not surprisingly, the phenomenon of ‘illiberal liberalism’ is as rampant in India as elsewhere in the free world. The same story of blindness or duplicity, evidently, prevails here. LeLi journalist-intellectuals and the periodicals they patronize, often train their polemical guns on the Hindu Right, but seldom on Muslim and other forms of ‘minoritarian’ intolerance. They soft-pedal the latter as if it poses no real threat to Indian liberalism. If Sharia-like conditions are imposed on reluctant Muslims in Musim-dominated areas, or even on non-Muslims, they are silent,” writes Makarand R. Paranjape, an alum of St. Stephen’s College, Delhi and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and former English professor at JNU in JNU: Nationalism and India’s Uncivil War (Rupa, 2022)

Nevertheless, disappointment with the incumbent administration runs deep within the JNU faculty. Last September, JNUTA wrote to President Droupadi Murmu, the official Visitor to JNU, demanding removal of Vice Chancellor Santhishree Pandit over what it described as a “crisis of governance” and “lawlessness” in the institution. The letter also urged the President to invoke her powers under the Jawaharlal Nehru University Act, 1966, to annul the termination of Rohan V.H. Choudhari, an assistant professor at the Centre for Political Studies, citing “unauthorised absence”. Moreover, it alleged that decisions related to appointments, promotions, confirmations, allocation of housing, and even the functioning of statutory meetings were being taken unilaterally without consultation with the Academic Council. Meetings of university bodies were being held online despite repeated requests for physical sessions, only to “thwart real deliberation” and secure “rubber-stamp” approvals. “The culture of compliance that the VC is trying to create and a liberal academic culture don’t go together,” says JNUTA president Surajit Mazumdar.

In addition to dilution of academic autonomy and “infiltration” of BJP/RSS sympathisers into the faculty, promotion of new Centres dedicated to study and research of subjects close to the ideology of the establishment are changing the character of JNU, charge faculty spokespersons. They cite a recent proposal to establish a Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Centre for Security and Strategic Studies within the School of International Studies to promote Indian strategic thought that has been given the green light. This centre will study Maratha military history, guerrilla warfare, naval tactics, and governance, offering courses, diplomas, and doctoral programmes on ways and means to integrate ancient wisdom into modern defence studies and counter Western-centric views. A second centre, the Kusumagraj Centre, will also promote Marathi language and literature at JNU. Both centres are backed by the Maharashtra state government, which has allocated Rs.10 crore for the project.

Menon: “imaginary achievements”

Moreover, recently JNU has also established centres for Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Studies to incorporate Indian knowledge systems into mainstream research. These centres have been set up under the School of Sanskrit and Indic Studies in consonance with the mandate of NEP 2020. Moreover a Special Centre for National Security Studies (SCNSS), established in 2018, analyses defence and security issues through traditional Indian knowledge systems. According to Prof. Nivedita Menon (quoted earlier) the promotion of these knowledge systems is “superficial, celebratory, boastful, factually inaccurate and replete with imaginary achievements”.

Beyond academics and administration, the famously liberal environment of JNU has undergone a discernible change. The varsity’s vast open spaces designed by Basil Spence, architect of Sussex University (UK), were meant to function as “amphitheatres of ideas,” where teachers and students were encouraged to “walk and talk, discussing the latest seminar or the last piece of research, or a distinguished lecture.” While these public spaces are still open to students for debate, JNUSU leaders say it is a struggle for students to get committee rooms or auditoriums for lectures and events. Even the 9 p.m debates in the mess which were a regular feature of JNU’s intellectual life, have petered out. The process of seeking permission has become difficult, if not impossible, with sign-offs required from the hostel president, warden, the provost, and then the dean — a three-day process. Against this until 2016, permission from one professor was enough.

As a result, there is growing antagonism between newly recruited faculty and students and increasing confrontations in classrooms. Right now the newly elected JNUSU office bearers are protesting that Prof. Swaran Singh, three-time chairman of the Centre for International Politics, continues to remain on campus despite being indicted for sexual harassment by an Internal Complaints Committee (ICC).

Nevertheless despite a vitiated confrontationist environment in which ABVP student activists experience minimal difficulty in holding prayer meetings and processions across the campus, JNU remains a beacon of academic hope for aspiring upwardly mobile students countrywide, because of its reputation as an island of excellence in a sea of aridity. It consistently ranks high nationally (often #2 by NIRF) and is ranked among the Top 1000 globally (#558 in the QS World University Rankings 2026), with an A++ NAAC grade, and is recognised by UGC as a University of Excellence.

JNU is still the institution which shaped Kanhaiya Kumar, the son of an anganwadi worker from Bihat in Begusarai, Bihar, into a national leader; where Pradeep Shinde was transformed into an associate professor of sociology despite the challenges of being a Dalit. JNU has a record of being on the right side of history. Its students went to jail during the Emergency, rescued Sikhs during the 1984 riots in Delhi (many of them were hidden in Jhelum Hostel) and they marched from Gangotri to Rishikesh during the Tehri dam agitation.

The question is whether it can keep its character and soul intact in the New India.

“There is a fake narrative”

An international relations Ph D from JNU, Santishree Dhulipuli Pandit was appointed Vice Chancellor of JNU in 2022, the first woman to hold the position. Excerpts from a hurried interview.

An international relations Ph D from JNU, Santishree Dhulipuli Pandit was appointed Vice Chancellor of JNU in 2022, the first woman to hold the position. Excerpts from a hurried interview.

The JNUTA has accused you of high handedness. What is your response?

JNUTA propagates half truths to promote their fake narrative. In JNU there’s a re-emphasis on research and academics. During the past four years, academics and research has been conducted in a peaceful yet vibrant atmosphere. In April, JNU was awarded the prestigious PAIR (Partnerships for Accelerated Innovation and Research) grant, becoming a Hub institution to mentor other universities in basic sciences. We have also signed an MOU with IIT Delhi.

This is a great national institution that serves the nation via the lowest fees in the world to provide high-quality higher education. We attract students from 15 states countrywide; faculty recruitment has also seen diversity. Moreover as the first woman VC of JNU, I have empowered more women to top positions in the university. Women faculty has increased from 18 percent to 28 percent during the past four years.

What are your main achievements?

We’ve implemented the National Education Policy 2020 and introduced the Indian Knowledge Systems in all streams. We have democraticised and decentralised the functioning of 14 schools and 10 special centres. We’ve improved infrastructure by mobilising public and private funds and have encouraged Indian languages in interdisciplinary studies. I am the first VC to conduct four convocations in person for the ninth time in JNU’s history.

Are JNU’s core values still the same as they were at the beginning?

JNU celebrates unity in diversity and is a nationally renowned space of critical thinking, debate, discussion and deliberations with multiple narratives. We are improving our infrastructure to become comparable with the best worldwide. We are set to reduce the fee for international students by up to 80 percent.

Runaway subsidisation

JNU students: rock-bottom fees.

One of the big secrets of Indian education is over-subsidisation of higher education, an issue about which there is political and media silence since most media pundits and others down the pecking order are beneficiaries. This is iniquitous because over-heavy subsidisation of tuition and residential accommodation in publicly-funded colleges and universities attended mainly by middle class students comes at the cost of inadequate provision for early childhood and primary education.

Rock-bottom tuition fees payable by scholars in the postgrad, showpiece Central government funded Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU, estb.1969) are a classic example of this enduring iniquity. Tuition fees for MA, M.Sc, MCA programmes range form Rs.120-10,120 per month. Moreover hostel accommodation in this wholly residential university sited on a green campus in the heart of Delhi where hotel room rents average Rs.5,000-10,000 per night, is Rs.240 per month for a single room and Rs.120 for double occupancy. It’s also pertinent to note that a substantial number of JNU Ph D scholars who have cleared the UGC exam are awarded UGC/CSIR junior and senior research scholarships ranging from Rs.31,000-35,000 per month.

S.P. Mishra

Such heavy subsidisation of higher education — widely acknowledged as a personal benefit cf. primary-secondary education which is regarded as a public good — is exceptional to India. It’s well-known that college/university fees are sky-high for American school-leavers, and that total student debt has reached alarming levels in the US. Likewise, in the UK, it’s normative for school-leavers, to take bank loans to pay for higher education and that loans are returnable after an income threshold is crossed. In China’s top-ranked Beijing University, arts and science study programmes are priced at Rs.3.35 lakh per year against India’s top-ranked JNU’s Rs.1,440-121,440.

“The degree of subsidisation of higher education in India is indefensible. Almost 40 percent of the education budgets of the Central and state governments are allocated for higher education at the expense of public early childhood and primary education, with government schools having to make do with pathetic infrastructure, misgovernance, mass teacher absenteeism, multigrade teaching and poor nutrition. The public interest demands the end of universal tuition subisdisation of higher education and introduction of means tested fees. Under the present system, middle class students in colleges and universities are snatching foundational early years learning from poorest children,” says Dr. S.P. Mishra, an alum of Bangalore and Pondicherry universities and currently Promoter-Director of the Hyderabad-based India Career Centre, a students counselling firm.

Add comment