Sombre golden jubilee of India’s pioneer community college

Fifty years after its initiatives in rural education, healthcare, solar energy, water conservation, handicrafts, waste management and wasteland development have transformed the lives of millions in the neglected outbacks of hinterland India, the overwhelming majority of citizens are unaware of this unique institution, writes Dilip Thakore

Early this year as the country was recovering from the unwarrantedly prolonged 82 weeks lockdown of all education institutions from preschool to Ph D, the golden jubilee year of the pioneer but largely unsung, Barefoot College, Tilonia, Rajasthan (BC, estb.1972) passed almost unnoticed.

Apart from a few puppet shows and its annual Tilonia Bazaar staged in Jaipur and Delhi and celebrations in Tilonia (pop.4,000) and surrounding villages, the golden jubilee of arguably the most successful and high-potential initiative in rural education and development passed unheralded. Because of sustained establishment — including media — disconnect with rural India, the overwhelming majority of citizens are unaware of the existence of Barefoot College, let alone its pioneer initiatives in rural education, healthcare, solar energy, water conservation, handicrafts, waste management and wasteland development which have transformed the lives of millions in the neglected outbacks of hinterland India.

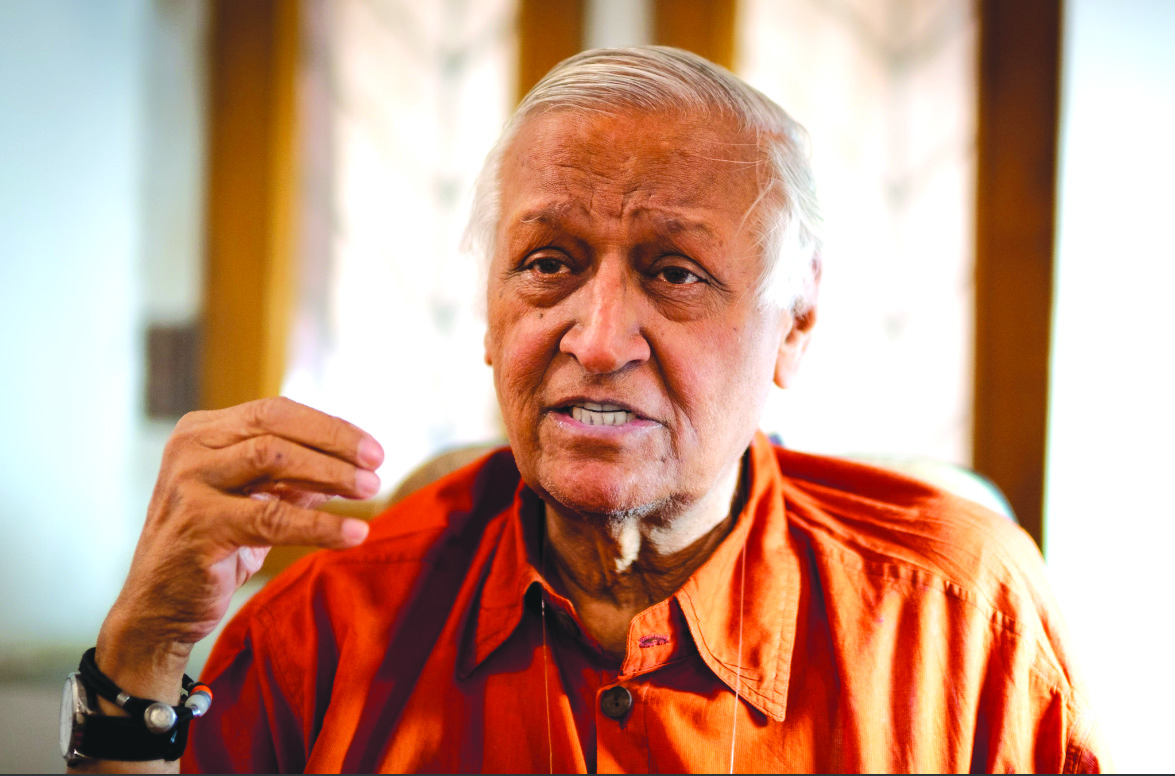

That half a century after Sanjit (‘Bunker’) Roy, an alum of the top-ranked The Doon School, Dehradun and St. Stephen’s College, Delhi forsook a promising career in the civil service in favour of drilling open wells for drinking water and irrigation in Tilonia, and 100 bone dry, water-stressed villages in the desert state of Rajasthan and registered the Social Work & Research Centre (SWRC) aka, Barefoot College, this institution — felicitated by the Dalai Lama, Prince Charles and Bill Clinton among other notables — is largely unknown back home, is a telling commentary on the indifference of the establishment to rural India which grudgingly hosts 60 percent of the country’s 1.30 billion citizens.

The genesis of rural India’s backwardness is the Left turn taken by Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, a natural sciences graduate of Cambridge University (UK), ignorant of elementary economics and the subcontinent’s long history of private enterprise. Born into the wealthy family of Motilal Nehru, perhaps the most successful lawyer in pre-independence India, Jawaharlal was schooled in the elite Harrow College and Cambridge, where under the influence of Britain’s trendy Bloomsbury Square socialists he naively became enamoured with communism and the Soviet-style centrally planned heavy industry development model. In essence this model, officially adopted by the Congress party under Nehru’s direction, necessitated siphoning rural and national savings for promotion and development of heavy industry — coal, steel, power, fertilizer etc — public sector enterprises (PSEs). Inevitably, the agriculture sector, which at the time supported 80 percent of the population, suffered severe infrastructure and logistics deficiencies and near-famine conditions. PSEs mismanaged by commerce-illiterate politicians and bureaucrats, aka the neta-babu brotherhood, conspicuously failed to generate promised surpluses (‘profit’ was — and remains — a dirty word in the leftist lexicon) for investment in rural infrastructure and development, especially primary education and healthcare.

The outcome of the disastrous Left turn imposed upon the newly independent nation by the Nehruvian Congress party — Mahatma Gandhi and Sardar Patel had strong reservations against Nehru’s juvenile fascination with the Soviet-style command-and-control economic development model — is division of post-independence India into urban India and rural Bharat. Seventy-five years after independence, it is very easy to distinguish citizens of these two goods and light industries model), agriculture and rural development was cruelly neglected (as it was in Stalinist Soviet Union), urban India is not totally indifferent to immiseration of rural Bharat. There were some individuals who stepped forward to aid and enable the people of other India.

Also Recommended: Barefoot College, Tilonia

Shortly after he graduated from St. Stephen’s with a Masters degree in English, Sanjit (Bunker) Roy, a three-times national squash racquets champion and son of an Indian Railways engineer and mother, a former trade commissioner to the Soviet Union, was all set for a career in the elite Indian Administrative Service (IAS). However, deeply moved by graphic news reports of hunger and starvation deaths in rural Bihar which experienced an unprecedented famine in 1966-67, the young postgrad volunteered to dig wells “as an ordinary labourer” in Rajasthan’s water-stressed Ajmer district.

This volunteer stint transformed into a five-year period. “My real education started when I witnessed water diviners, traditional bonesetters, midwives and carpenters at work in rural Rajasthan. They planted the seed of Barefoot College in my mind. At that time it wasn’t the teachings of Gandhi or Marx but exposure to ordinary people with traditional knowledge, grit, determination and amazing capability to survive with dignity and self-respect without any official support, who inspired promotion of the college. These ideas were reinforced with extensive study and teachings of Mahatma Gandhi who believed that prosperity of India’s 600,000 villages was the prerequisite of national development,” recalls Roy.

[userpro_private restrict_to_roles=

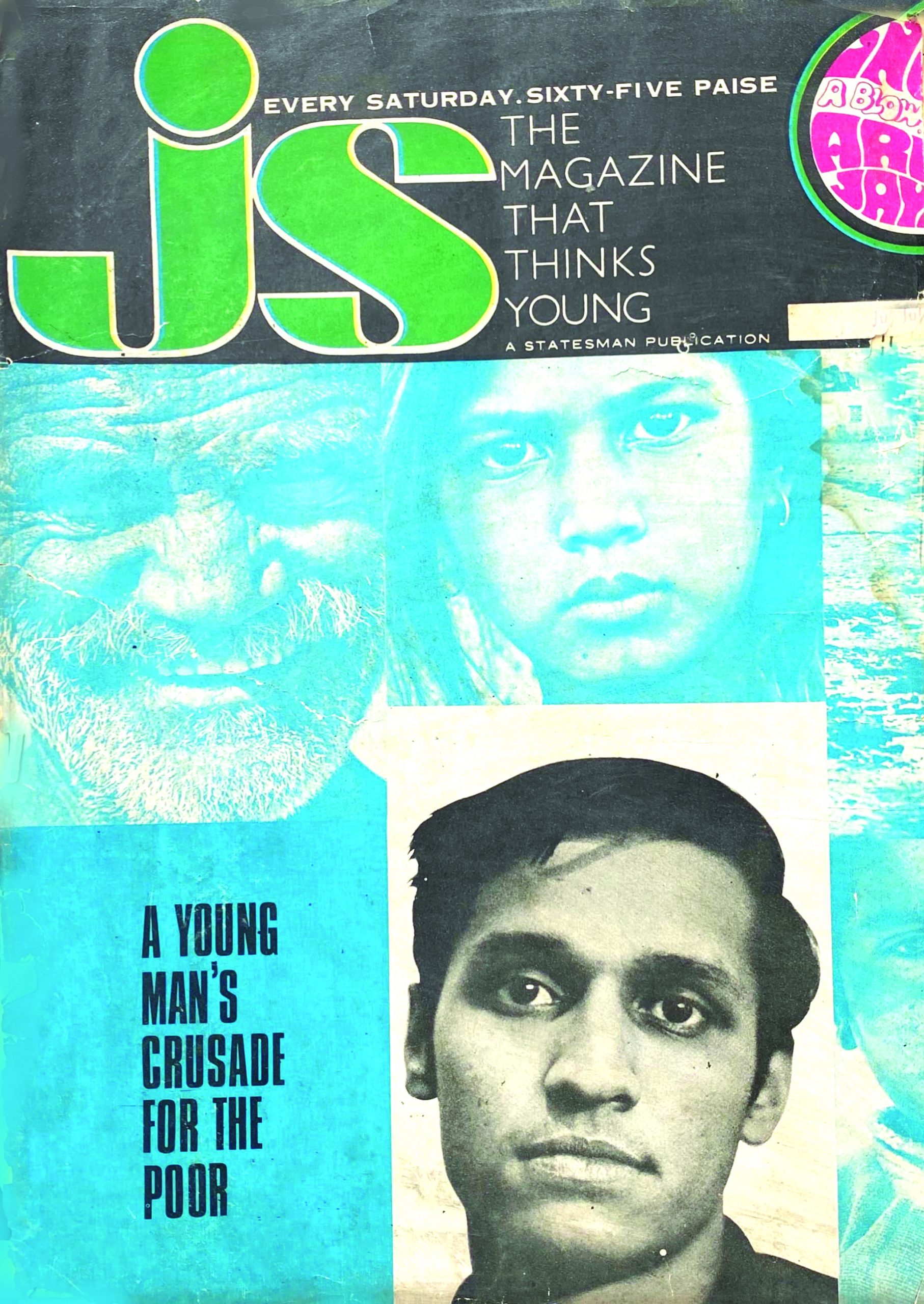

While toiling and learning in desert conditions in rural Rajasthan, Roy got a lucky break when his story came to the notice of Desmond Doig, editor of the Calcutta-based Junior Statesman, a magazine promoted by The Statesman, then the city of joy’s undisputed #1 daily. A novel cover feature written by Seetha Crishna which included photographs shot by then budding photographer Raghu Rai, detailing the young idealist’s dreams and aspiration to establish a community skilling college in a backward village attracted widespread attention, because of Roy’s elite education and Delhi establishment credentials. His grandfather was director-general of the Geneva-based Food and Agriculture Organisation and communist uncle Indrajit Gupta served a short-stint as Union home minister. The JS cover story prompted the government of Rajasthan to award Social Work & Research Centre (SWRC) registered on February 16, 1972 under the Societies Act, 1860, a dilapidated warehouse in Tilonia village at the nominal rent of Re.1 per year.

“The bureaucrats who approved the lease were convinced that with my background, I wouldn’t last long in the village because graduates of elite institutions were believed to be weak and soft. Living in rural India required staying power, sacrifice, grit and determination which they were sure I didn’t have. Fifty years later, I am still here in Barefoot College,” says Roy with evident satisfaction.

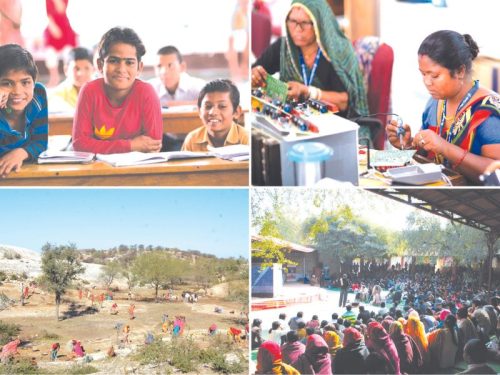

Half a century later, Roy who married social activist and trade unions champion Aruna Jayaram in 1970 (no children), has cause to be proud of the track record of the alternative education and rural regeneration institution designed and painstakingly nurtured by him. Over the past 50 years, SWRC/Barefoot College has educated 90,000 children who assist their parents in farming and livestock rearing and attend BC’s 250 night schools in ten states. Moreover, to inculcate the habit of school attendance, the college has provided early childhood education and supplementary nutrition to over 300,000 children in its preschools. Other BC initiatives include marketing and logistics support to 25,000 rural artisans in 48 villages, and the college’s unique globally acclaimed Solar Mamas programme under which 1,708 illiterate and semi-literate women from 96 countries have been trained to become barefoot solar engineers. After returning to their native villages, they have electrified 75,000 rural homesteads around the world (see box p.50).

“Yet perhaps BC’s greatest accomplishment is that we have devised an integrated village development model which reduces dependence on urban professionals by demonstrating that it is possible for poor and semi-literate rural citizens to serve their communities as barefoot solar and water engineers, architects, teachers, health workers, communicators and even computer programmers,” says Roy.

Undoubtedly, over the past half century since Roy and his rural comrades-in-arms willingly adopted the descriptive nomenclature of Barefoot College because “millions of under-privileged citizens of India who pass on traditional knowledge, skills and wisdom of their forefathers sit on floors and live and work barefoot,” it has progressively established an impressive record in forestry, rainwater harvesting, skilling rural solar and water engineers and training paramedics, including village dentists. Yet BC’s greatest impact has been on the socio-emotional psyche of the country’s rural majority reduced to second-class citizenship.

Continuously denied acceptable quality primary education (as routinely testified by ASER annual surveys) and learning English — the language of upward mobility — by venal state politicians focused on recruiting vernacular kith and kin into government schools and neck-deep in textbooks commissioning and printing rackets, and simultaneously being denied fair prices for farm produce, citizens of Bharat, the other India, have been reduced to the status of pathetic supplicants. The rich repository of village India’s traditional wisdom and skills have little value in the new society shaped by an urban bourgeoisie focused on primitive capital accumulation. Barefoot College’s greatest achievement is that it has provided citizens of Bharat an alternative decentralised socio-economic development blueprint for rural regeneration and self-reliant prosperity.

The history and career trajectory of Hanuman Sharma, the son of an anganwadi (preschool) helper who made himself literate by signing up in a Barefoot College night school, provides a good case study. In 1987, Sharma signed up with BC as a student-volunteer. Learning by doing and working with BC’s barefoot water engineers, he has since transformed into a highly respected forestry and environment rejuvenation professional who has orchestrated planting of 900,000 trees in 400 arid acres of rural Rajasthan, and has discovered 92 medicinal plants being purchased by the ayurvedic pharma industry. Coterminously, he has developed a technology for converting village waste into organic compost and nutrients for soil regeneration.

“I am very grateful to BC for restoring my self-respect and providing me the opportunity to serve my rural brethren. Now my mission is to transform deserts into forests and educate and train others to follow in my footsteps and make rural India prosperous,” says Sharma with disarming modesty.

Likewise Laxman Singh, a hydro geology postgrad of Rajasthan University, thanks his lucky stars that he forsook the option of relatively well-paid government employment and came aboard Barefoot College in 1987. Over the years he has acquired legendary reputation as a rainwater harvesting (rwh) and water conservation technologist. On the BC, Tilonia campus his team of barefoot engineers has built a massive 400,000 litres rwh underground tank beneath the college amphitheater and engineered solutions to increase campus water storage capacity to 2 million litres. Moreover, 600 government schools in Tilonia district and 1,600 statewide, have been made water and toilets sufficient by BC engineers.

“Although we use traditional technologies to make villages water sufficient, these technologies are continuously upgraded through innovation. For instance, we have substituted traditional lime and water coating with ferro cement. To be able to green desert areas and help poorest people to raise their standards of living is a very satisfying vocation,” says Laxman Singh, a member of the apex level management team at Barefoot College.

Indeed, even at the risk of repetition, perhaps the greatest achievement of Barefoot College is that it has infused a surge of self-confidence and can-do spirit of self-reliance into citizens of rural Bharat, neglected by government and the establishment. With their elected representatives routinely co-opted into the establishment which has barely concealed disdain for backward, ill-educated kisans, there’s dawning awareness in village India that they have to develop local leaders with adequate knowledge of capital light alternative technologies to improve living standards in Bharat.

A prototype leader empowered by BC is Ram Karan, a class VIII drop-out who was admitted into BC as student-volunteer in 1975. While specialising as a water engineer, moved by the pathetically subordinate status of rural women obliged to work at home and on farms as under-paid labour, he set about organising women’s rights groups. The result: a verdict from the Supreme Court in 1981 (Sanjit Roy vs. Government of Rajasthan) compelling the state government’s PWD (public works department) to pay women equal wages.

Today in 68 villages around Tilonia women are asserting their equality and working as solar fabricators, mechanics, water engineers and architects. They are fully involved in developing traditional rural technologies. It’s very important for urban government officials and people to understand that unless women, regardless of education background are encouraged and empowered, prosperity cannot come to rural India,” says Ram Karan, a commerce graduate of Rajasthan University and a member of BC Management Committee.

Barefoot College’s positive impact on status of women in village Rajasthan — one of India’s most socio-economically backward states (annual per capita income Rs.115,000 cf. Goa: Rs.422,149) — is exemplified by Kalawati Devi, who assists Ram Karan in BC’s women’s empowerment mission. Schooled until class V and widowed in 1993 with two girl children to raise, she enrolled as a volunteer with BC in that year.

“Three decades ago the status of women in villages was pitiable. All of us were in ghunghat (head covering) and dared not express our opinion on any subject. Today we are confident and outspoken and unafraid to voice our complaints about discrimination and domestic abuse in our village panchayats. Most women have abandoned ghunghat and in villages around Tilonia it is common to witness women working as solar and water engineers and teaching in night schools. Bunkerji has totally transformed the lives of women in the Ajmer district by empowering and encouraging us to assert our rights. My hope is that this movement will spread and empower all women across the country,” says Kalawati Devi.

Likewise, the extraordinary evolution of Lilawati Devi Gujjar, a class III dropout who signed up with BC as a student-volunteer in 2003, is an indicator of the dormant potential of rural Bharat’s women citizens if they are provided minimal education and opportunity. Over the past three decades, Lilawati Devi has transformed into an internationally acclaimed solar engineer who heads the college’s unique transnational Solar Mamas project.

Under this unprecedented skilling initiative begun in the millennium year 2000, grandmothers (“they are certain to return to their villages after training”) from 96 under-developed African, Asian and South American countries are provided six months intensive training on the BC campus in Tilonia to qualify as solar engineers. Their airfare and modest pocket money is paid by the Union ministry of external affairs. Thus far over 1,700 solar mamas have returned to 1,500 villages, and have electrified 75,000 homes around the world. Also a master tailor who teaches tailoring when not tutoring solar mamas, Lilawati Devi has travelled (“alone”) to Zanzibar and Fiji to teach her craft and has addressed rural development conferences in Germany and France.

“I am very thankful that I was given the opportunity to train 1,708 women from around the world to light up their homes and spread the women’s empowerment philosophy of Barefoot College which has completely changed the mindsets of thousands of rural communities in Ajmer district. My wish is that the number of Barefoot colleges should multiply around the country and harness the power of rural women to make India a prosperous nation,” says Lilawati Devi.

Nevertheless, though during the past half century, Barefoot College has totally transformed the landscape of Rajasthan’s Ajmer district and through its SAMPADA (Society for the Advancement Motivation of Peoples Action and Development Alternatives) network enabled establishment of clones in 13 states of India, BC’s tried, tested and proven rural development model has not been sufficiently scaled. Fifty years after the college admitted its first batch of student-volunteers, rural India is under-educated, poor and backward, contributing a mere 16 percent of the country’s GDP. This ‘failure’ has strewn the apples of discord in SWRC/Barefoot College campus and prompted an institutional schism.

New Zealand-born Meagan Fallone, a fine arts and engineering alumna of University College London and Harvard University, first visited BC in 2010. “I was amazed and excited with what I saw. The founding team led by Mr. and Mrs. Roy have undoubtedly made an indelible contribution to the rural development sector in India. The notion of a formally educated and privileged couple, leading a diverse team from rural and urban areas, contributing formal and informal skillsets to serve rural communities, was totally disruptive and extraordinary. Indisputably SWRC/Barefoot College has made an incredible contribution to the India landscape overall and charted a new path for social enterprise in India, heavily informing the global development debate in ways that will resonate for many years,” acknowledges Fallone.

Given her impressive academic qualifications and several decades work experience in the US and Europe, she was welcomed into the top management of the college and appointed CEO in 2011. However after serving as CEO of SWRC/Barefoot College for over a decade, Fallone experienced impatience with “slow scaling” of the institution.

“The 2008 financial crisis caused considerable disruption for non-profits as our funding streams changed. Firstly, our donors became much more results oriented and conscious of specific outcomes. They demand professional practices, good governance, programme innovations and alignment with UN Sustainable Development Goals. Secondly, new types of funding — CSR and impact investment — entered the scene and the Central government tightened regulations relating to foreign funding received by NGOs,” says Fallone.

Although Fallone is reluctant to elaborate, “tightened government regulations” is undoubtedly a reference to the BJP/NDA government’s crackdown on offshore donations to NGOs, many of whom are suspected to be supportive of Islamic terrorism and religious proselytism, a red rag to the BJP, a Hindu majoritarian political party. Therefore, foreign donations to Amnesty International were proscribed and for a brief while disallowed to Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity.

Thus was born Barefoot College International Ltd (BCIL), a s.8 company under the Companies Act, 2013 which was registered in 2015 in Harmara village in the Ajmer district. And one of the first initiatives that BCIL has undertaken in a big way is to modernise its administration and operations with introduction of new digital technologies. According to Fallone, although SWRC/Barefoot College and BCIL are now separate and distinct entities, they have a common heritage and similar goals. And she is delighted to report that BCIL has got off to a good start.

“My heart is full when I see the children of long standing BC staff, back at work with us and leading new programmes, community work and helping to build BCIL in India and abroad. Many of these young people have gone on assignment to work in our international locations for brief periods and have returned to India to apply their learning and new ideas. In the new company we continue to run the programs of the parent BC — renewable energy and Solar Mama training, community health and agri-livelihood development, women’s entrepreneurship, and establishment of more colleges abroad. Our team which is mentored by Bhagwat Nandanji, one of the founders of Barefoot College, has established new colleges in Senegal and Guatemala this year and will inaugurate another in Fiji by the end of this year. Moreover, a high-potential new initiative has been the development of digital content for rural areas that overcomes language and literacy barriers,” says Fallone.

This digital content initiative includes design of a super app being developed by Fallone in collaboration with Innoterra Zug, a Switzerland-based agro-tech company promoted by Indian origin entrepreneur Ron Pal, to provide farmers with “knowledge, information and climate positive practices”. The company has established a major office in Mumbai, and the app will be hosted on its ambitious digital platform. “It will be a game-changer for rural India,” predicts Fallone.

Although Fallone believes that BCIL is a 2.0 version of SWRC/Barefoot College committed to similar objectives, and that the two institutions have mutually agreed to take different paths to attain similar goals, Bunker Roy — promoter of BCIL when it was registered as a non-profit under the Companies Act, 2013 — is outraged by Fallone’s “hijack” of the company.

“I was one of the founder members of BCIL when it was registered under the Companies Act in 2015. It was an act of good faith. But I deeply regret its management’s unethical and dishonest track record since then. They hacked the BC website and tried to hijack our logo and trademark. A cease-and-desist legal notice was sent to them to stop exploiting and abusing the global brand and influence of BC but that didn’t stop them. A case has been registered in the Delhi high court,” says Roy.

Since 2021 when SWRC/Barefoot College announced a clean break from BCIL, Roy has made grave charges of funds defalcation, cheating and identity theft against Fallone and the BCIL management. According to Roy, since BCIL employees were evicted from the Tilonia campus, the national headquarters of BCIL comprises seven 40 ft containers in Harmara village. “They don’t run any schools or training programmes for Solar Mamas. Their senior staff live in cities and come occasionally to Harmara on the pretext that they work from home. It’s only a question of time before they abandon their rural staff who will have nowhere to go. They have a Rs.50 lakh salary bill every month with 70 percent paid to paper qualified professionals who live in the nearby town of Kishengarh and cities across India. The government of India has taken a dim view of their poor-quality work in Africa and establishment of Barefoot Vocational Training Centres (BVTCs) in Senegal. Burkina Faso, Liberia and Tanzania. Severe action is going to be taken against them,” says Roy.

The bitter split in Barefoot College has occurred at an unfortunate time when urban-rural inequalities have deepened in the aftermath of prolonged disruption of the economy by the Covid-19 pandemic. Although Fallone and the BCIL management comprising an array of young professionals detailed on the company’s website (www.barefootcollege.org) evidently believe that the power of two enterprises driven by similar objectives and ideals will accelerate rural revival and regeneration, courtroom battles may distract both parties going full throttle.

This confrontation is likely to slow rollout of the tried, tested and proven BC rural regeneration model across the country. Meanwhile, establishment resistance to the low-cost BC education model is pervasive within the academy and establishment.

Repeated emails and phone calls to Dr. A.K. Singh, director and Dr. Rashmi Aggarwal, head of education at the Indian Council of Agriculture Research (ICAR) to ascertain their views on the Barefoot College rural development model remain unanswered. Ditto email messages and phone calls made to Dr. Ashok Gulati, renowned agriculture scientist and faculty at ICRIER, Hyderabad.

Perhaps the sole establishment personality who obliquely endorses the BC rural development model is Sharad Patel, whose father Lallubhai, a believer in the Gandhian model of rural development, promoted the Aspee College of Horticulture & Forestry, in Navsari, Gujarat in 1975. This college is affiliated with the Navsari Agriculture University, ranked among India’s Top 5 agriculture universities by EducationWorld (April, 2022).

“Formal agriculture universities can happily co-exist and supplement the work of informal institutions such as Barefoot College. For instance, our trust and college supports Lokbharati in Sanosara, Gujarat which propagates agriculture practices based on self-reliant village communities. We believe that formal agriculture universities should support informal agriculture and rural development institutions such as Barefoot College which has an excellent record in rural development and upliftment,” says Sharad Patel, an alumnus of Gujarat and Michigan universities, managing director of the Mumbai-based American Spring and Pressing Works Pvt. Ltd (“one of India’s largest agriculture spraying equipment manufacturers”) and member of the academic council, Navsari Agricultural University and Junagadh Agricultural University (Gujarat).

However, viewed in the context of the persistent — and unnecessary — India vs Bharat divide and oppressive establishment-rural patriarchy-money-lenders coalition determined to ensure that agrarian India remains a supplier of cheap farm produce and purchaser of cost-plus manufactures and services, it is painfully obvious that the Barefoot College model is unlikely to receive meaningful government, establishment or middle class support. On merits the Union and state governments should have embraced and incorporated the BC rural development model into their five-year plans and budgets decades ago. But this hasn’t happened because replication of the BC development model would devalue the certification and degrees issued by formal schools and universities. In this connection it’s pertinent to note that as a matter of policy BC doesn’t formally certify any of its student/adult volunteers or faculty because certification will prompt “migration to urban India”.

The deep, perhaps ideologically-inspired hostility of urban India and the establishment towards informal learning-by-doing community colleges such as BC, is explained by Jesse Hartigan, an American academic, who visited Tilonia in 2007. Writing in Innovations — Technology, Governance and Globalisation, a journal of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he says: “Those most hostile to the Barefoot approach are people who have invested a great deal in acquiring an education through the official system and then applying their misguided ‘expertise’. The very idea of semi-literate women being able to manage and control initiatives at the village level, undermines those hard-earned credentials and credibility, and even threatens the existence of their jobs. Indeed, one result of the Barefoot approach in India where it is most widely replicated, has been replacement of cost-intensive initiatives by low cost and labor intensive initiatives, providing gainful employment within villages.”

This analysis explaining indifference and half-hearted official and establishment support — and indeed sustained media blackout — is seconded by Anuprat (Dunu) Roy (no relation), an IIT-Bombay alum and currently director of the Hazard Centre (HC, estb.1980). Supported by the Delhi-based Sanchal Foundation, HC provides technical assistance to “people in need” to solve livelihood problems by connecting them with experts from a panel of 400 selected professionals ready and willing to provide pro bono assistance.

“The reason why the Barefoot College rural development model has not become popular countrywide is that rolling it out nationally requires large committed funding for training and mentoring student-volunteers at scale. Moreover meaningful government and middle class support is unlikely because a large supply of informally trained barefoot engineers will devalue the expensive degrees and qualifications of middle class professionals whose incomes will be hit as public dependence on their expertise and service decreases,” says Dunu Roy.

Half a century after it was registered with the limited objective of raising subsistence standards of the water-stressed people of Tilonia village, Barefoot College, which has replicas in 13 states countrywide and through its unique Solar Mamas project has made an imprint in 96 countries worldwide, has designed, tested and implemented its rural development model with considerable success. As the country celebrates 75 years of independence, a national consensus needs to emerge that long-neglected second class citizens of Bharat, deserve better lives.

Barefoot College track record

Water conservation and harvesting

• From the early years of drilling open wells, the Social Work and Research Centre (SWRC) aka Barefoot College (BC), has utilised the traditional technology of collecting groundwater in tankas.

• Thus far, 70 billion litres of water has been harvested and stored in rainwater tanks, ponds and small dams. Moreover, safe drinking water has been provided to 1,650 rural schools in 20 states across India.

• Barefoot College has installed 1,735 hand pumps in 530 villages in four states and trained 1,766 people as hand pump mechanics who are employed by the government of Rajasthan.

Education & schooling

• Barefoot College has educated 90,000 working children in 250 night schools in ten states nationwide. Over the past half century, three generations of young people have gone through the Barefoot learning experience.

• Shiksha Niketan, a day school run by SWRC since 1989, has played an important role in fulfilling aspirations of young people in Tilonia and neighbouring villages.

• BC has provided early childhood education to over 300,000 children.

• Bridge school. This is a residential school for children of migrant families, or dropout children from vulnerable sections of the local community who never enrolled in formal school.

• Rural artisans. Leather and tanning, women’s handicrafts, block-printing and designing began in 1974.

• The annual Tilonia Bazaar was initiated in 1975.

• Hatheli Sansthan project. Working to improve villagers’ livelihoods through entrepreneurial initiatives.

• BC has nurtured 25,000 artisans in five districts and 48 villages of Rajasthan.

Women empowerment

• Recognition of women as contributors to the economy and their role as wage workers, led to formation of women’s groups in 11 villages in 1981-82.

• These groups educated public opinion against sati, rape and organised women to demand minimum wages, leading to a favourable Supreme Court verdict (Sanjit Roy vs Rajasthan State Govt (1983)) for equal wages.

• Barefoot College also trains rural women health workers, midwives, masons, hand pump mistris, fabricators, solar engineers and community radio jockeys.

• More than 7,000 women have been nurtured to develop leadership skills and educated about the processes of democratic participation.

• Barefoot dentists, pathologists, health workers and midwives assist the rural population to access efficient medical care. Over 300,000 patients have been treated in the past 50 years.

Solar energy

• The first solar project was initiated on the Tilonia campus in 1996, training local stakeholders on how to manufacture solar lanterns.

• Started in 2000, the Solar Mamas Programme trains illiterate and semi-literate women from non-electrified villages on design, fabrication, installation and repair of solar home-lighting systems.

• In 2008, the Solar Mamas Training Programme was adopted by the Union external affairs ministry. Since then BC, Tilonia has trained 1,708 illiterate or semi-literate rural women from 96 countries who have electrified more than 75,000 households worldwide saving 45 million litres of kerosene from polluting the environment.

• More than a million people across the world have light and energy through decentralised, clean solar electricity, replacing kerosene lamps.

Media & communication

• Puppets are Tilonia’s ambassadors. Glove puppets made of recycled paper, which are easy to use, have replaced the traditional string puppets. Jokhim Chacha is the bard, mascot and commentator of Tilonia.

• A rich repertoire of plays, skits, songs have addressed a range of issues such as water conservation, education of the girl-child, land and ownership, environment, women’s issues and caste taboos.

• 2,000 Barefoot Communicators have been trained to produce interactive puppet shows. Over 300,000 people have watched these performances in 3,000 Indian villages since 1981.

Environment protection

• Barefoot College has been promoting plantations in wastelands, pasture land, government schools and nurseries across Rajasthan.

• The BC Plant Nursery Team manages more than 20,000 native trees and plant species on its campus in Tilonia and neighbouring villages.

• In Village Tikawada, 40,000 trees have been planted on wasteland with the community involved in their upkeep.

Waste management

• BC has been proactively empowering local communities to devise low-cost, sustainable, solid waste management systems.

• With establishment of the triple pillars of water harvesting, environment greening and waste management, several communities have reaped the benefits of this co-ordinated action.

• Barefoot College has created Rajasthan’s first zero waste and plastic-free village: Chhota Narena. This programme has been successfully implemented in four other villages.

Global Solar Mamas project

A unique initiative of Barefoot College (BC), Tilonia which has won tremendous international goodwill and appreciation for India in the third world — where Indian diplomats have a reputation for sanctimonious lecturing about how to further the cause of international peace, justice and development, unmindful of their own shabby front and backyards — is its sustained programme for training women barefoot solar engineers from developing nations, and Africa in particular.

Introduced in 2005, thus far the Solar Mamas programme, which mainly trains elderly and middle-aged women on the premise that they are invariably more committed to their village hearths and homes, has ‘graduated’ 1,708 solar mamas from 26 countries including Kenya, Zambia, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Chad, Bur-kina Faso, Congo as also Colombia, Jordan, Gautemala and Peru. Under this unique programme, illiterate and semi-literate women are interviewed and selected and flown into BC campus in Tilonia, where they undergo a six-month residential training programme under the supervision of a BC-trained Indian faculty of 25 master trainers including eight women. In a refreshing departure from traditional diplomacy, the entire travel, food, lodging and training expenses of foreign solar mamas are borne by the Union ministry of external affairs.

During their stay here, women from abroad are thoroughly trained not only to assemble and repair electric circuits — which contain 35 components — but also to connect them with bought out solar panels and storage batteries and to install and maintain integrated solar energy units back in their villages. The training programme is based on learning-by- doing and presents communication challenges, as the trainees are usually illiterate and don’t speak any language but their own.

The diplomatic impact in terms of goodwill for the government and people of India generated by BC’s Solar Mamas programme is worth many multiples of the annual expense (Rs.2-3 crore) incurred. While they are here, elderly women from all over the world not only train to become solar engineers, but also learn about rainwater harvesting and witness the socio-economic changes of BC’s education and women’s empowerment programmes first-hand. “When they return to their villages and communities, they become agents of change and development. And in the nights when their villages are lit up while surrounding areas are in darkness, presidents, prime ministers, dictators and policy makers notice and hopefully, are inspired,” says Bunker Roy.

“Our model challenges the formal education system”

Dilip Thakore interviewed Sanjit (‘Bunker’) Roy, founder-director of Barefoot College. Excerpts:

Congratulations to you and Barefoot College (BC) on your golden anniversary. What were your objectives when you promoted BC 50 years ago?

My real education started when I saw water diviners, traditional bonesetters, midwives at work. That was the humble beginning of Barefoot College. At that time, it wasn’t Gandhi or Marx who inspired the work of the college but very ordinary people with grit, determination, and the amazing ability to survive with dignity and self-respect without any official support. These ideas were reinforced by extensive study of the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi who believed that the prosperity of India’s 600,000 villages was the prerequisite of national development. My objective was to bring this rich repository of indigenous knowledge, skill and wisdom, still abundant in Bharat of 2022, into mainstream thinking through Barefoot College.

How satisfied are you with the growth and achievements of Barefoot College?

I am never satisfied but our record speaks for itself. During the past 50 years, Barefoot College has helped 90,000 working children attend 250 night schools in ten states of India. Three generations of young people have gone through the Barefoot learning experience. Over 300,000 children have also attended our preschools.

Over 2,000 Barefoot College communicators have been trained to produce interactive puppet shows to propagate modernisation ideals. Over 300,000 people have watched these performances in 3,000 Indian villages since 1981 to change anti-social — especially anti-women — attitudes among rural communities.

Barefoot College has also trained 1,708 illiterate or semi-literate rural women from 96 countries to become solar engineers. These women have electrified more than 75,000 households worldwide, saving 45 million litres of kerosene from polluting the environment.

Despite BC having proved itself as a successful model for rural development and prosperity and being acclaimed internationally, the BC model has not been replicated in all districts of Rajasthan, let alone India’s 600 rural districts. What’s your comment?

We strongly believe the semi-literate and illiterate have the power, confidence, capacity and the knowledge and skills to provide extraordinary, affordable goods and services to their own communities. One of Barefoot College’s greatest accomplishments is reducing dependence on urban professionals and demonstrating that poor semi-literate men and women can serve their own communities as barefoot solar and water engineers, architects, teachers, health workers, communicators and computer programmers.

Rigid formal education systems of government and private schools coupled with over- dependence on paper certification to prove competence, are the main reasons why the Gandhian Barefoot College rural development model has been rejected at every level. Because it challenges the formal education system.

What’s your assessment of the contribution of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research and its affiliated 71 public agriculture colleges to the Green Revolution and rural development?

When M.S. Swaminathan was secretary of the Union ministry of agriculture in the 1980s, he introduced a very innovative project called Lab to Land. Hundreds of young agricultural scientists were sent to villages all over the country and lived there for six months. Their job was to interact with farmers, understand their problems and provide simple technical solutions. This programme was discontinued because agricultural scientists complained it was too difficult for them to be productive while residing in villages. The Lab to Land project needs to be re-introduced.

What’s your prescription for eradicating poverty from rural India?

There is no urban solution to a rural problem. Over generations, Rural India that is Bharat, has devised simple inexpensive solutions to problems of poverty — drinking and irrigation water, indigenous education, traditional healthcare systems, livelihoods and working with dignity and self-respect.

Paper qualified urban professionals have systematically destroyed and undermined the cultural value and respect for traditional knowledge, indigenous skills and village wisdom because rural professionals are not ‘certified’.

How optimistic are you about rural India becoming a middle-class society?

When I first started residing in Tilonia 50 years ago, village sarpanchs used to ride bicycles. Today they have multi-crore budgets and drive SUVs. They flaunt degrees from universities, but their mindset is still 19th century. Now palatial residences, air-conditioned homes and multistorey buildings are sprouting in villages. Powerful farmers with hundreds of acres in names of joint family members don’t pay agriculture or income tax. Their sons and daughters are gram sevaks, thanedars, patwaris and tehsildars. Thus they are law-makers and virtually untouchable. Regrettably, a lumpen middle class has come to stay in the larger and richer villages of India.

The gap between the rich and poor in rural society has widened. I am very disturbed by what’s happening.

[/userpro_private]

Add comment