China: Affirmative action resentment

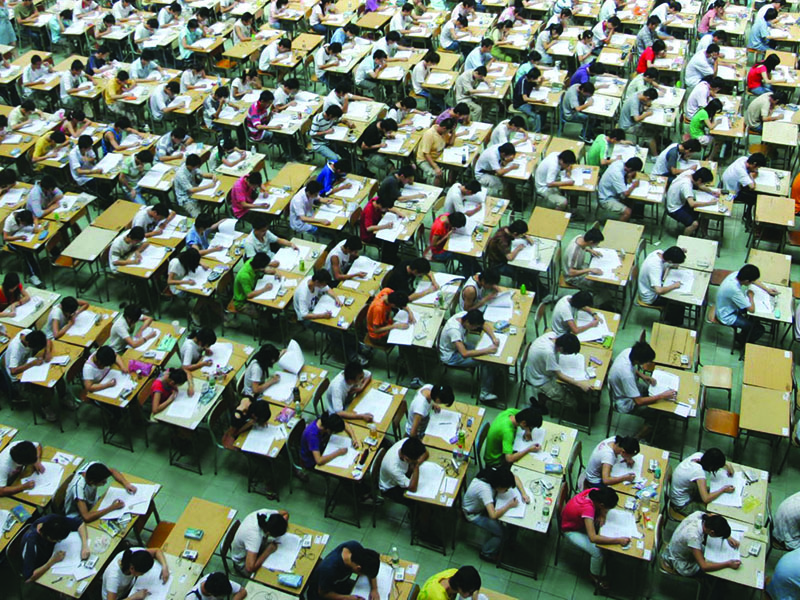

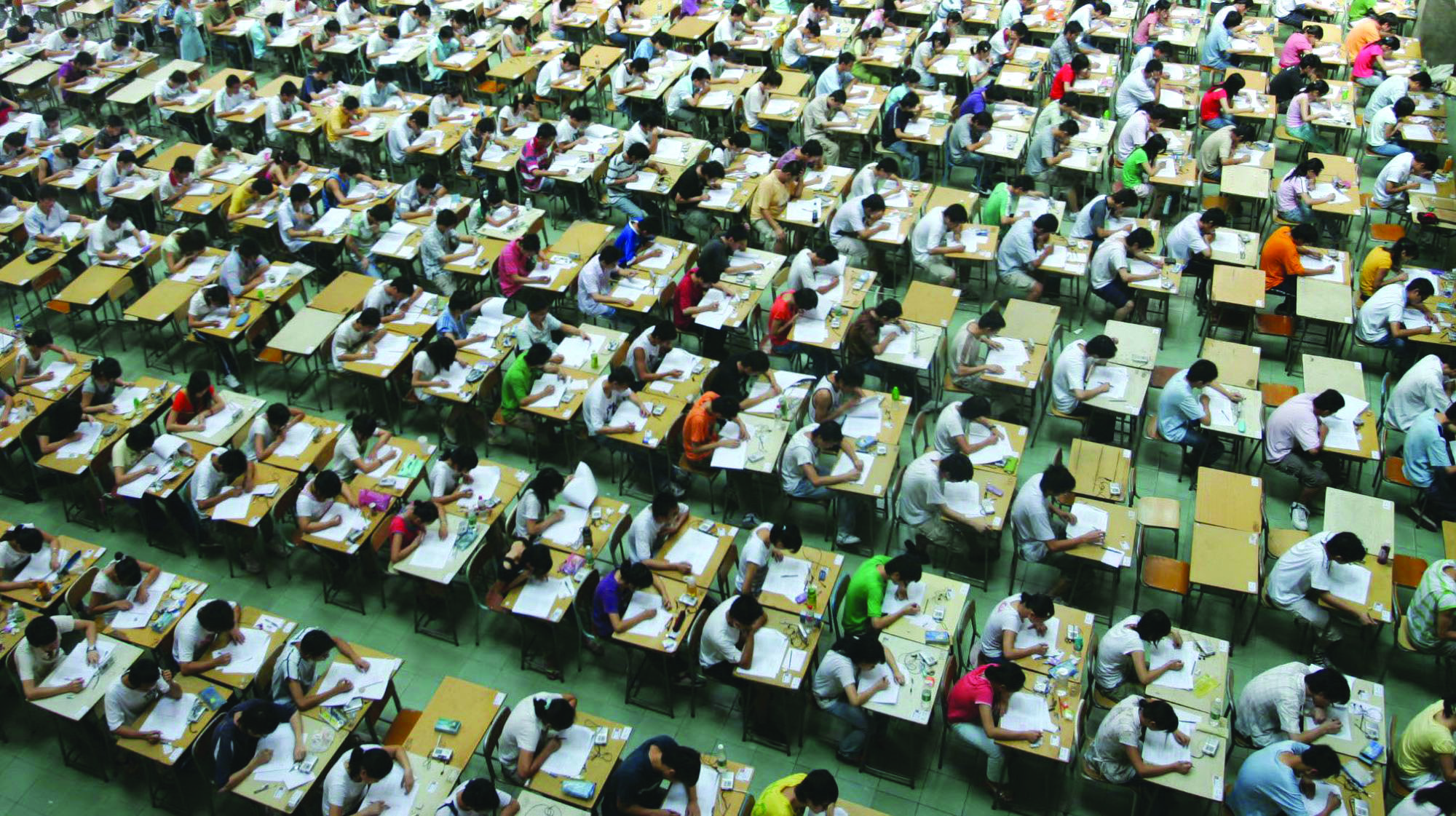

On June 7, millions of young people wrote the world’s largest academic test. China’s university-entrance exam, known as the gaokao, is punishingly difficult. Students spend endless hours cramming for it. But it is also widely accepted as meritocratic. Work hard, score well and, no matter what your social background, you will get into a good college.

Yet the test is administered in ways that don’t seem so meritocratic. Local governments are allowed to produce their own versions of gaokao, with different questions and scoring methods. Students in elite cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, enjoy an easier route into local universities, which include some of the country’s finest.

The maximum possible score on the gaokao can change from year to year and may vary according to province, but it is usually 750. Most provinces award extra points (ranging from 5-20) to certain groups, such as military veterans and Chinese who return from overseas. Until recently, some provinces showered points on students who exhibited “ideological and political correctness” or had “significant social influence”. But such arbitrary criteria led to corruption and calls by the Central government to phase them out.

Unsurprisingly, the extra-points system has bred resentment among those who receive no help with their scores. Lately their ire has been directed at members of minority groups, who have long been awarded grace marks simply on the basis of their ethnicity. The policy, begun long ago, aims to assimilate minorities into the dominant Han culture. But some Han, who make up over 90 percent of the mainland’s population, wonder why communities that nationalists often paint as disloyal and ungrateful, should receive such an advantage.

The state itself has backed away from the policy in recent years. In 2014, the Central government indicated a desire for it to be re-evaluated. Since then, a number of provinces — such as Anhui, Jiangsu, Shandong and Shanxi — have stopped giving extra points to minority students.

Under Xi Jinping, the Communist Party has promoted the idea of a single Chinese identity, an effort that has involved trampling on the freedoms of minority groups and abolishing affirmative-action policies. But the authorities justify the latest moves as a way to improve “exam equality” and prevent cheating in the admissions process. Officials also claim that the schools in regions with big minority populations have improved so much that the bonuses are no longer needed to even things out.

This is questionable. Students from minority groups still lag behind their Han peers. And if the government were so concerned about fairness, it would do away with other extra-point schemes, such as one targeting Taiwanese students in the attempt to lure them to mainland universities. But none of this is likely to make young Han cramming for the gaokao feel any less anxious.

Add comment