China: BRI-Higher ed connection

While China’s higher education strategy is often characterised by its focus on competition, with a range of excellence initiatives pouring additional funding into a select number of institutions over the past two decades, one of the most interesting recent developments in the nation is an initiative that is ostensibly about collaboration.

While China’s higher education strategy is often characterised by its focus on competition, with a range of excellence initiatives pouring additional funding into a select number of institutions over the past two decades, one of the most interesting recent developments in the nation is an initiative that is ostensibly about collaboration.

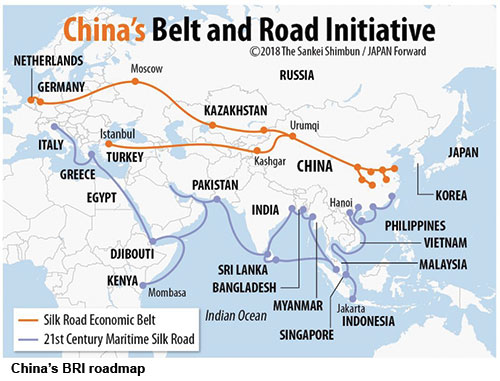

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), announced in 2013, is a £750 billion (Rs.67.3 lakh crore) scheme to extend Chinese influence across Asia, Africa and Europe through overland and maritime trade routes, infrastructure development and Chinese investment. The Chinese government describes the initiative as “a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future”. The BRI route takes in about 70 countries, which account for half the world’s population and a quarter of global gross domestic product. More than a quarter of these nations feature in the Times Higher Education Asia University Rankings 2019.

China leads this ranking for the first time this year, with Tsinghua University supplanting the National University of Singapore in first place. While its Beijing neighbour Peking University drops two places to fifth, a consequence of declines in its research and industry incomes, 16 of the 26 Chinese institutions in the Top 100 have held steady, risen or entered the list for the first time.

But to what extent will the country’s higher education success, coupled with the BRI, drive education forward across the whole of Asia?

Gerry Postiglione, professor in the faculty of education at the University of Hong Kong and an expert in the comparative sociology of Asian higher education, says China’s rising number of “world-class universities” represents “a potential long-term asset for engaging with the significant diversity of other leading research universities located in countries encompassed by the BRI”.

The Chinese government is supporting 42 universities to achieve “world-class” status, while 64 universities across the BRI route benefit from being included in their own countries’ excellence initiatives, notes Postiglione. “To position itself as a global economic hub by mid-century, the Asian region will need to cement its reputation for excellence,” he says. “For Asia to constitute more than half of global GDP by 2050 (it accounted for 41 percent of global GDP in 2016), it must raise the quality, diversity, cost recovery and governance autonomy of its institutions of higher education, especially its universities. China has a role here because its investment — as a developing country — in creating world-class universities has paid off in spades.”

Most Asian countries are approaching middle-income status, and building high-quality research universities will be crucial if they are to avoid the “middle-income trap” — a situation in which a country rises to a certain level of income and development but then stagnates, says Postiglione. “This requires resources and experience, both of which China has and wants to offer as part of its BRI,” he adds.

(Excerpted and adapted from The Economist and Times Higher Education)

Add comment