China: Gaokao shenanigans

Gaokao examinees: emergent grey industry

An ancient Chinese saying states that Meng mu san qian, the mother of Mencius, a sage, “moved three times” to find him the right study environment. Tiger mums worldover know the feeling, but few push harder than the Chinese. The game of cat and mouse the Communist Party plays with parents to stop them trying to game the system is legendary. The party has now released new rules to try to stop it.

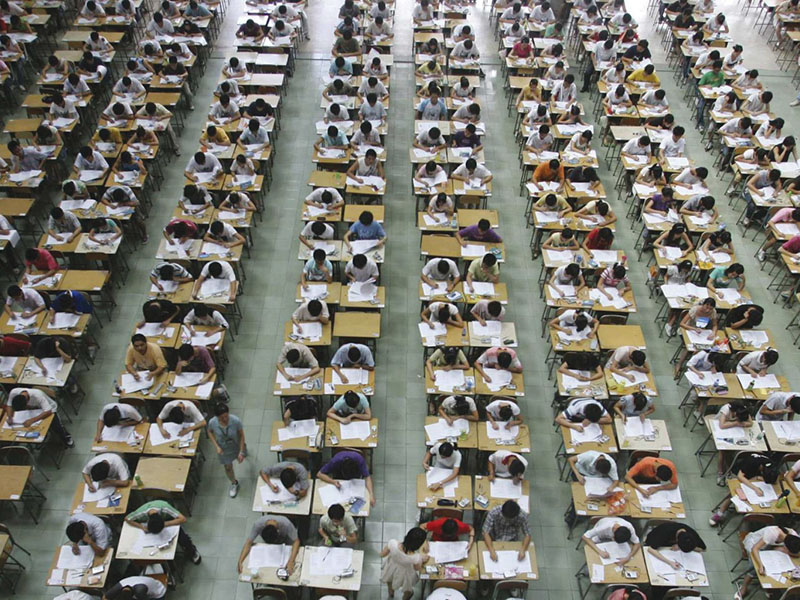

In theory, any of the 13 million students who write the annual gaokao entrance exam can qualify to attend a university of their choice if they achieve a good enough score. In practice, because of the skewed way seats are allocated by region, the competition is fiercer in populous provinces. So a small number of parents try to ‘move’ to less populous provinces.

That’s not always easy. To enroll your child at a college in another province might require buying a house, finding a new job, or bureaucratic wrangling to change your hukou, or household registration. So there is a temporary way by which some parents try to cheat the system. They keep their child attending the local school but, using bribes or connections, arrange for them to write the gaokao in another province. In one notorious case in 2021, the child of a head teacher in populous Hebei province (with about 600,000 test-takers) took the gaokao in Tibet (competing with just 40,000 locals). Public outrage ensued.

A grey industry known as ‘gaokao migration’ has emerged to help with these tricks. For a fee, consultancies offer to smooth things over with local officials and schools. One such firm in Henan province told The Economist that for 60,000 yuan ($7,700), they could arrange for a student to sit the exam in Hainan, a rural southern province.

Worried about the anger that cheating and educational inequality creates, on February 7, the education ministry issued new rules demanding schools send a report on every student twice a year, to make sure all are studying and taking exams in situ.

It would help if China relaxed regional quotas for universities or scrapped them altogether. But resistance from provinces which benefit from the current system makes that all but impossible, says Li Hongbin of Stanford University. One such place is Beijing, home to many rich and powerful figures. In 2012, reform-minded officials proposed allowing more people to write gaokao in the capital. But Beijingers protested that it would make the exam more competitive for their children. After much ado, the reform was stifled. Parents will continue to act like the mother of Mencius.

DeepSeek success strategy

The success of artificial intelligence platform DeepSeek, developed by a relatively young team including graduates and current students from top-ranked Chinese universities, may encourage more students to pursue opportunities at home amid a global race for talent, predict some experts. The emergence of DeepSeek upset global financial markets in January as the model appeared to rival the performance of ChatGPT and other US-designed apps, at much lower price.

Liang Wenfeng, DeepSeek’s chief executive, himself a graduate of Zhejiang University, has spoken previously about the benefits of hiring students from domestic universities. In an interview with Chinese media outlet 36Kr, Wenfeng described his team as “recent graduates from top universities, some PhD candidates in their fourth or fifth year, plus a few who graduated only a few years ago”. “The V2 model of DeepSeek was not produced by people returning from overseas, they are all local. The top 50 talents may not be in China, but maybe we can create such people ourselves.” Indian higher ed leaders, please note.

Over the past decade, the Chinese government has continuously stressed the importance of aligning university majors with advancements in science and technology, as well as integrating academia with technological innovation and industry. The success of DeepSeek, which became the most downloaded app in the US shortly after its release on January 20, suggests these policies are paying off.

“DeepSeek’s founding team and core technical members are almost entirely products of China’s domestic higher education system, reflecting the strength of the country’s academic-industrial ecosystem,” says Marina Zhang, associate professor at the University of Technology, Sydney’s Australia-China Relations Institute. “Many DeepSeek team members have worked on national-level AI initiatives — such as Tsinghua’s Air Lab and Peking University’s Wang Xuan Institute — where they combined cutting-edge academic research with practical industry experience. This smooth transition from lab work to product development has been central to DeepSeek’s rapid progress.”

Beijing has also emphasised the importance of self-sufficiency and embedding “Chinese characteristics” into the country’s education systems. In parallel, DeepSeek is distinctly Chinese in nature, likely shaped by its developers’ backgrounds.

“Unlike teams that rely on overseas technological pathways, DeepSeek’s members have developed in-depth knowledge of Chinese natural language processing and multimodal understanding — capabilities that directly address AI challenges in the Chinese context,” says Zhang. “For instance, DeepSeek’s large language models outperform international competitors in tasks involving Chinese semantic understanding and classical Chinese text generation.”

However, the government is still calling for greater integration as concerns about widespread graduate unemployment continue across China. In a recently released education strategy, the government reiterated calls to “set up urgently needed disciplines and majors” and increased collaboration between universities and businesses.

China is also keen to tackle the outflow of young talent from the country, to study and work abroad. Although the pandemic stemmed the flow of students to other countries, China remains one of the top senders of students abroad. Geopolitical tensions, including the first Trump administration’s controversial China Initiative, have contributed to the recent return of many Chinese scientists to their home country, Zhang predicts that the success of DeepSeek could inspire “more Chinese STEM graduates to pursue opportunities at home”.

“The growing evidence of high-impact careers and globally significant achievements within China’s tech ecosystem is a powerful motivator,” she says. “A similar trend emerged during the first wave of internet start-ups, when top-performing graduates chose to join local tech ventures rather than seek opportunities abroad or join multinational firms. Today, DeepSeek’s story reinforces this pattern, demonstrating that China’s innovation ecosystem can rival Silicon Valley in terms of ambition, resources and impact.”

Also read: China: English lingo disinterest

Add comment