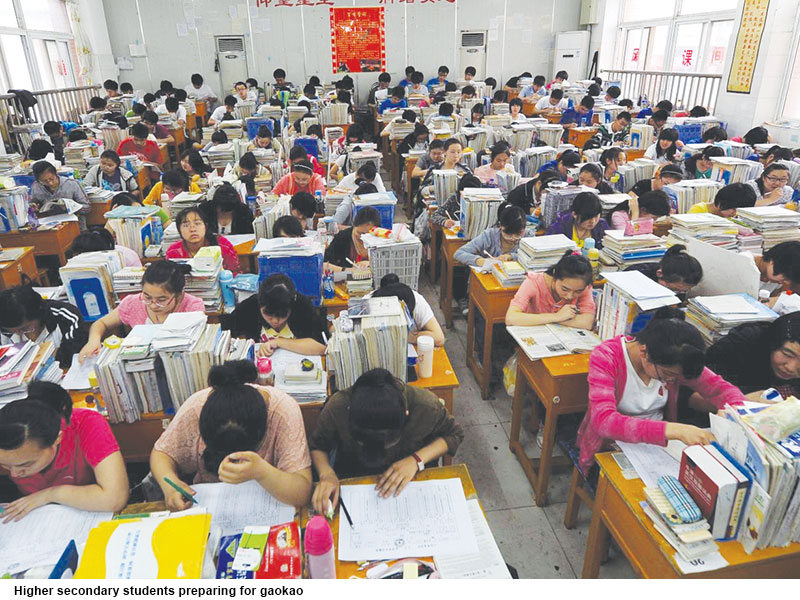

For children from bottom-of-pyramid households, China’s infamous gaokao, a punishingly hard university-entrance exam taken by over 10 million students every year, offers the only chance to escape a life toiling on farms and factories. As a result, Chinese education has long involved little more than rote learning, aimed purely at the gaokao. Pupils attend late-night cram sessions and shoulder twice as much homework as the global average.

But the People’s Republic’s deep reverence for tests is not shared by reformist educators and some head teachers, who somewhat belatedly have started to downplay them. They have a radical vision — of reducing study loads, expand the curriculum and encouraging students to take up hobbies. Nanjing, a former imperial capital, is the centre of their experiments.

In 2016, Nanjing Number One Secondary School, the city’s oldest and most competitive, began to let students borrow points from a “marks bank” to boost low grades. These are repaid by deducting points scored in a later test, or earned from good classwork. The aim is to take a bit of pressure off exams. At the school, teachers and students are encouraged to be “on an equal footing”, an appreciative former pupil wrote in an online forum. Nanjing Number One has a vibrant students union, a literary society and other clubs. Its university-acceptance rate this year was 95 percent, a record for the school.

Yet the scene outside Nanjing Number One in late July, soon after the gaokao results were released, was not of jubilation. Dozens of angry parents brandished placards demanding the head teacher step down. They blamed their children’s lower-than-expected scores on what they saw as his attempts to make light of tests. More traditional schools in Nanjing, they noted, churned out top-scorers. Nanjing Number One mollified the protesters by extending compulsory revision sessions to 10 pm for final-year students. On social media, theories circulated that officials who advocated a less demanding curriculum really just wanted to make it harder for students from humbler families to get ahead.

Many in China once supported what schools such as Nanjing Number One are trying to do. In the early 2000s, a bestseller about raising children in the West, Education for Quality in America, popularised the idea of suzhi jiaoyu. The term refers to a well-rounded education that attaches importance to building character as much as knowledge. It guides most of Nanjing’s more liberal teaching. The author, Huang Quanyu, became a household name in the middle class, writes Teresa Kuan, an American academic, in Love’s Uncertainty: The Politics and Ethics of Child Rearing in Contemporary China (2015). In 2010, China published a ten-year education plan which admits that the country’s teaching is “relatively outdated”, and that people have “strong yearnings” for suzhi jiaoyu.

From next year, a tweaked gaokao will give students leeway to pick and choose some subjects, beyond the compulsory ones. But China is reluctant to overhaul a test that remains remarkably meritocratic. “By sticking with the exam, we waste students with other talents. By moving too far away from it, we disadvantage poor kids,” says Wang Tao of East China Normal University. It is not that loving parents don’t want their children to have fun. Rather, as one mother in Nanjing puts it, relaxed classrooms are “just no use” if they don’t get a pupil into a good university.

So quasi-military cram schools —“gaokao factories”, as they are known — still thrive. One such is Hengshui Secondary School in the northern province of Hebei. It has 18 branches across China, some of which reward students who get into top universities with tens of thousands of dollars. In 2018, one of them bought two decommissioned army tanks to flank its entrance, apparently to instil a sense of toughness among its students.

Wang says he’s glad to see “so much negotiation” under way, with educators pushing forward and policymakers following cautiously, even if parents are still resisting. Observant children at the museum in Nanjing will find, in addition to statues of prominent men who aced the keju, a bronze one of a person who failed it repeatedly: Wu Cheng’en, who was educated in Nanjing in the 16th century. Wu went on to write Journey to the West, one of China’s most celebrated novels.

(Excerpted and adapted from The Economist & Times Higher Education)