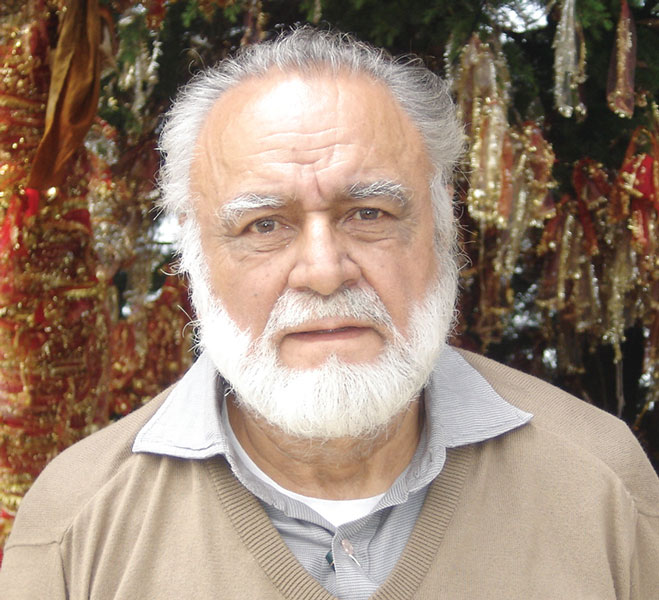

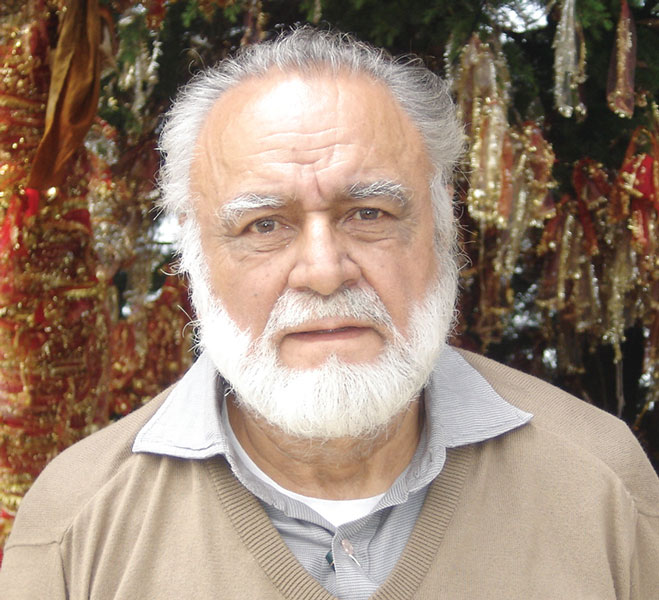

Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul, who passed away recently in London at the age of 85, was one of the most insightful, even if most controversial, writers of our time. A high-caste Brahmin descended from indentured labourers who had migrated from eastern Uttar Pradesh to Trinidad in the West Indies, Naipaul experienced a hard childhood until he won a scholarship to Oxford University, UK. Although he hated Oxford, he made England his home after graduating with a degree in English literature. But he never felt at home there. His rootlessness bothered and perhaps even agonised him, but it also prompted his development into an extraordinary writer of great acuity and perspicacity. As an outsider he was able to observe and analyse societies, especially third world countries, with rare, penetrating insights. What he witnessed and conveyed in his writing upset and offended many people. But he believed in telling the truth as he saw it, uncaring of consequences.

Naipaul was never politically correct. Throughout his life, he insisted on describing Africans and African-Americans as Negros. He boldly remarked that Africa and its people had no future. “Africans need to be kicked, that’s the only thing they understand,” he once wrote. Likewise, mocking Indian women who wear bindis on their forehead, he said it signalled “I have nothing in my head”. He also described the notorious fatwa of Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini on Indian-origin writer Salman Rushdie for penning The Satanic Verses (1988) as “an extreme form of literary criticism”.

His first book on India, An Area of Darkness (1964), an unsparing critique of socialist Nehruvian India, was banned by the government. In this book, he detailed a morning train journey, during which he witnessed people openly defecating beside railway tracks, without bothering to conceal themselves. Naipaul was aware that the raw truth can be hurtful, but he believed it needed to be told regardless of outcomes. He was repelled by much of what he saw in India, its squalor, corruption and pervasive poverty. The irony is that when he visited India for the first time in 1964, he was full of curiosity and eager to learn more about the land of his forefathers. I suspect he half thought that he might settle down in India to become more ‘rooted’. Fortunately, he did not and the world of letters and literature is richer for it. In 2001, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

His 30 books comprised memoirs, travelogues, novels and history. An Area of Darkness was followed by two more books recording his impressions of India — India: A Wounded Civilization (1977) and India: A Million Mutinies Now (1990). While Wounded Civilization was almost as scathing as An Area of Darkness, Million Mutinies was surprisingly mellow, even optimistic about India. After these books, Naipaul turned his severe gaze on militant Islam. His two frank and forthright books Among the Believers (1981) and Beyond Belief: Fact or Fiction (1997), outraged most of the Islamic world. Writing on the export of militant Wahhabi Islam fuelled by the petrodollars of Saudi Arabia, Naipaul wrote: “Islam has had a calamitous effect on converted peoples. To be converted, you have to destroy your past, destroy your history. You have to stamp on it, you have to say ‘my ancestral culture does not exist, it doesn’t matter’.” More controversially, his comment that the destruction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1992 was a “reordering of history” cheered India’s Hindutva militants. Never sparing, Naipaul said that as Muslim conquerors had destroyed many Hindu temples, the vandalisation of the Babri Masjid was overdue payback.

Nevertheless, while he prided himself on being brutally truthful, Naipaul was a bundle of contradictions. He claimed he ignored criticism, but when the late Behram Contractor, a journalist and humorist, bluntly opined that he regarded Dom Moraes as a better writer, Naipaul turned his back on him and retreated to the other end of the room in a sulk. On another occasion, at a party I hosted for him, one of my guests, a Dubai-based Indian, had never heard of him. Naipaul was enchanted and spent most of the evening talking to him!

After he was belatedly awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, I wrote an essay in which I pointed out that he had become more acceptable to the Nobel Prize committee after the terrorist strike on New York’s World Trade Centre in 2001, for his trenchant criticism of militant Islam. Evidently, Naipaul was unhappy that I made that linkage because, after a friendship of over four decades, I became persona non grata.

Was Naipaul a racist, enemy of Islam, and intolerantly right-wing, as some of his critics allege? Referring to African-Americans as Negros is hardly racism. Also, he married a Muslim. And one of his closest friends, Farrukh Dhondy, was a member of the Black Panthers and as leftist as you can possibly get without being a card carrying member of the Communist Party. My verdict is that it’s impossible to categorise V.S. Naipaul. He was too complex a personality and writer to fit into a slot. All one can say is that he has bequeathed to the world a unique legacy of work replete with marvellous insights and delightful prose.

Other articles by Rahul Singh:

Social media regulations require wider debate