Amar Farooqui (The Book Review, April)

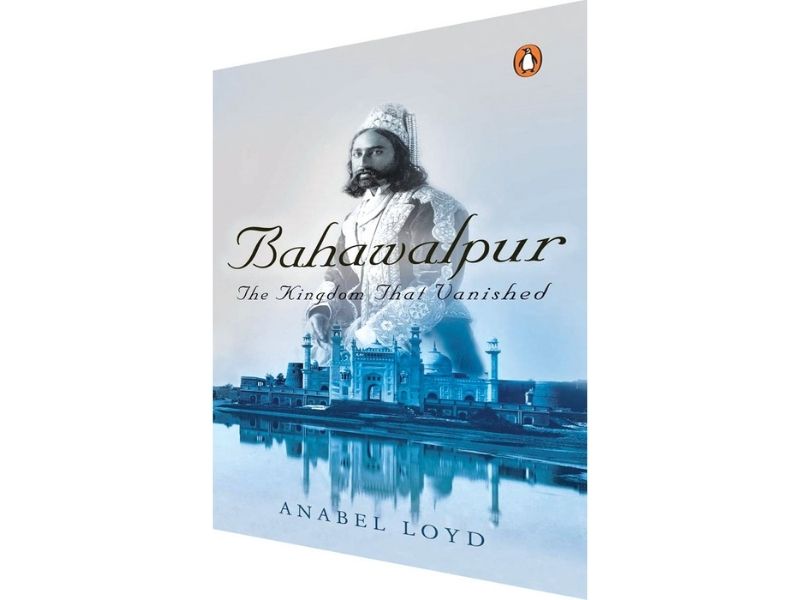

Anabel Loyd’s Bahawalpur is an account of the history of this princely state of the late colonial period, and its territories after accession to Pakistan when it ceased to exist as a distinct political entity. The processes whereby Bahawalpur was absorbed and new, frequently altering, administrative arrangements were introduced for the governance of its territories are discussed together with the fate of the erstwhile ruling family.

Loyd brings the story down to the ongoing disputes over the extensive properties of the family. Nevertheless, there is little reason to lament the end of princely rule in the state in the post-1947 period. Princely states in the subcontinent existed because British colonialism found them useful for stabilising and governing the empire. They acquired their legitimacy from the paramount power and in turn legitimised imperial authority. The end of British rule put an end to their relevance.

Loyd’s narrative is marked by a sense of loss, and perhaps even betrayal of the state and its ruling family. This is reflected in the nostalgic reference to Bahawalpur as the ‘kingdom that vanished’ in the subtitle of the book. The travails of the state after 1947 were a product of the political trajectory of Pakistan and not directly the outcome of its constitutional status as a former princely state.

By the time the British began penetrating this region in the early 19th century, the kingdom of Bahawalpur extended from the borders of Jaisalmer and Bikaner in the west, to the Sutlej and Indus in the north. It was sandwiched between Ranjit Singh’s kingdom in the north and Sind in the west. In view of its strategic location, in the early 1830s the British sought to enlist collaboration of the Bahawalpur court. The diplomatic expertise at the disposal of the East India Company was too much for the state’s ruling elites and soon they signed agreements which in the long run undermined the authority of the court.

The company would go on to use Bahawalpur as a base for its campaigns in the region when during the late 1830s and early 1840s Sind, Baluchistan, Punjab and Afghanistan became targets of its expansionist thrust. This strengthened the ties between Bahawalpur and the British, and gave the state considerable political importance.

A substantial part of the book deals with the several decades-long rule of Sadiq Muhammad Khan V, from 1907 to 1947; the period of transition from the integration of the state to its extinction in 1955, and his death in 1966.

Sadiq Muhammad was an infant when he succeeded his father in 1907 and was invested with full powers of a princely ruler only in 1924. It may be mentioned that the extent of a ruler’s ‘full authority’ was determined by the Crown. Between 1907 and 1924 the state was administered by a council of regency under British supervision.

Shortly before the administration was handed over to Sadiq Muhammad, a heavy financial burden was imposed on Bahawalpur in the form of its share of expenditure for a major irrigation scheme, the Sutlej Valley Project. Work on the project commenced in 1922. To meet its financial commitments, the state was obliged to take a massive loan from the British India government, the repayment of which proved to be a trap from which the ruler was unable to extricate himself. “An agreement with the Government of India (in 1936), for its liquation in annual payments for the next fifty years until 1986, became the sword over the head of the ruler of Bahawalpur,” writes Loyd. Colonial officials ignored the counsel of Bahawalpuri officials, who considered the project ill-conceived, especially as the water the river was capable of carrying was overestimated.

Partition brought a fresh set of problems. The tragedy of Punjab was replayed throughout the province, though the scale and details varied. In the case of Bahawalpur communal violence and bloodshed were definitely on a scale much lower than that in British Punjab.

Sadiq Muhammad assured Mahatma Gandhi that the state would extend full protection to Hindus, and “no-one would interfere with their religion.” V.P. Menon noted that Bahawalpur was “a paradise compared to East Punjab,” an indication of the contrast which the state presented to those parts of Punjab which the British had governed directly for a century.

In 1955, the state was absorbed into the administrative unit designated as West Pakistan under the One-Unit scheme, and divided into three districts, formally marking its extinction as a princely state. The erstwhile ruler retained some privileges, mostly of ceremonial nature.

The concluding chapters focus on the fate of the former ruling family after the extinction of the state, the manner in which it used its residual political and social influence, and the tussle for possession of historically significant palaces and forts of Bahawalpur State. Loyd’s portrait of Sadiq Muhammad in his twilight years as “a wealthy, retired and generally retiring gentleman in Sussex and London” after 1955 (he passed away in 1966 in London), is of an erstwhile ruler reconciled to the loss of his domain.

This book also reproduces a lengthy extract from some charming reminiscences of Sheila Covey, whose father was head gardener at Sadiq Muhammad’s residence in Sussex. Covey describes him as a character out of P.G. Wodehouse.

Obviously Sadiq Muhammad was happier spending time in the English countryside watching children play cricket, than attempting to resurrect his vanished kingdom.