Impressive explainer

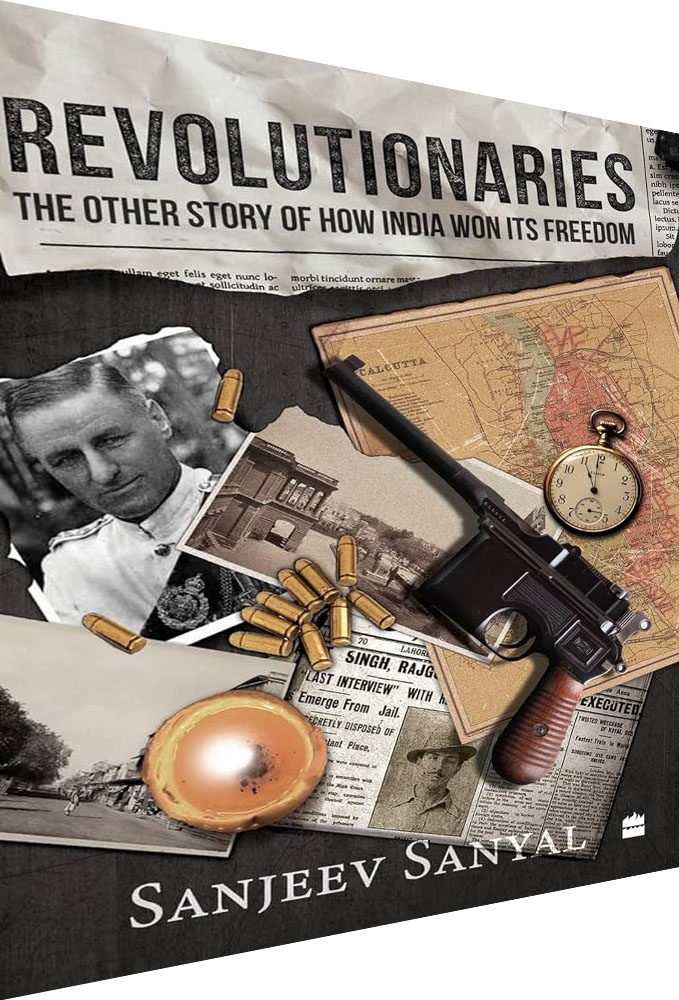

Revolutionaries: the other story of how India won its freedom

Revolutionaries: the other story of how India won its freedom

Sanjeev Sanyal

Harper Collins

Rs.599

Pages 351

To counter public amnesia the author uses the methodology of micro-history to intervene into the mainstream narrative of India’s freedom struggle as it has been ‘received’ since 1947

Reading this alternative history of how India won its freedom from British colonial rule, I was reminded of eminent British historian Prof.

E.H. Carr’s pertinent monograph which posed the question What is History? And proceeded to opine that it “reflects one’s own position in time” and “what view we take of the society in which we live.”

For economist Sanjeev Sanyal, “correcting” the mainstream narrative of India’s freedom movement is an important imperative. Several revolutionaries whose lives and activities are showcased are personalities that the generation described as midnight’s children, born in the independent Republic of India, are unfamiliar with. Some acquired national and international fame as iconic individuals who offered resistance to British imperial domination. A few were admired for their leadership and acts of exceptional courage in regional spaces.

Unfortunately many others who suffered and sacrificed their lives for the country’s freedom, were marginalised or sidelined. Remarkably, Sanyal, to pen this alt history, visited sites of rebellion and underground activities countrywide and abroad, family homes, the Andaman Cellular Jail, prisons and sites of incarceration and torture.

The author’s grievance is that “generations of Indians were sold a narrative where the contribution of these revolutionaries were shown to have been no more than random acts without coherent objectives, and, consequently, as having no impact on the course of events.” Post-independence school textbooks and national days he believes, exclusively highlight the role of Mahatma Gandhi’s ideology of non-violence and activities of Indian National Congress leaders.

Other revolutionaries have been systematically marginalised, if not summarily dismissed by mainstream historians. Sanyal’s effort is to resurrect the heroic deeds of nationalists such as Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal. But why it should be at the cost of undermining the achievements of other leaders and freedom fighters is a moot question.

To counter public amnesia, Sanyal uses the methodology of micro-history to intervene into the mainstream narrative of India’s freedom struggle as it has been ‘received’ since 1947. According to Sanyal, revolutionary resistance to British colonial administration, draconian repressive laws, physical torture, criminalisation and penalisation, was spread over at least three generations in the aftermath of the Sepoy Mutiny aka First War of Independence in 1857. But such often violent revolutionary resistance was by and large read as confined to regional areas and projected as individual acts of bravery linked to organised networks in Europe, America, Canada, Japan, even Russia.

Japanese pan-asianism, Russian communism, German socialism, Italian facism and Irish nationalism are traced as influences on indigenous akhada culture represented by the Anushilan Samiti, Jugantar, Abhinav Bharat etc.

Fragmented information about these revolutionary networks is pieced together alongside biographies of obscure as well as comparatively well-known revolutionaries including Aurobindo and Barin Ghosh, Vinayak Savarkar and Ram Prasad Bismil, among other bravehearts. Rash Behari Bose, architect of the Ghadar Mutiny (1915) and founder of the Indian Independence League (IIL) who passed on his baton to Subhas Chandra Bose is well represented in the narrative.

The exploits of the Indian National Army against British India and its 1943 slogan of Dilli Chalo were too dramatic to keep out of mainstream textbooks. However, Sanyal justifies controversial politicised initiatives underlining the “symbolic importance” of the recently installed statue of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose on Kartavya Path, Delhi.

The picture that unravels is of youthful idealism and enterprise, connecting with “imagined communities” across the country, of resolute faith and conviction in witnessing a liberated motherland. Underlying the call for liberation were dare-devil plans of the cited revolutionaries to equip themselves with arms and ammunition through armoury and warehouse raids, learning to make indigenous bombs and disseminating inflammatory pamphlets and monographs. Against this, the response of the colonial administration was pervasive suspicion, incarceration without trial, torture and counter violence like the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

To control this civil-war-like situation and in protest against the Partition of Bengal (1905), mass non-violent, non-cooperation and swadeshi movements struck root.

But public participation on a large scale had its pitfalls especially in the context of mounting communal tension. The Moplah riots in Kerala are highlighted as one of the causes of Gandhi-hatred as he tried to deny its link to the Khilafat movement. Likewise, the naval mutiny (1946) is seen as creating a further rift between Gandhi and Jinnah that “triggered” British prime minister Clement Attlee’s announcement that the Cabinet Mission had recommended full self-government to India.

In any large scale and ambitious political programme gaps and fissures are certain to surface. So this narrative is replete with instances of betrayal and treachery, revolutionaries turning approvers or becoming complicit with repressive authority. Global events like the two World Wars confuse the scenario as does the birth of ‘isms’ — communism and socialism — which splintered indigenous revolutionary groups.

What is singularly missing in the narrative is an overall vision that could unite diverse, complex discourses into a pattern. Arbitrary connections are made between events and impact. The epilogue cursorily explains the social processes through which political parties and allegiances developed in forcibly partitioned independent India.

History is seldom static; newly discovered facts will inevitably prompt revisions of past narratives. But every hypothesis is expected to follow a rigorous process of empirical enquiry, examining facts to establish principles.

This is necessary for a fresh understanding of how revolutionary and non-violent movements coalesced to win India her freedom from colonial rule.

Jayati Gupta

Add comment