India’s ivory tower agriculture universities

Established on huge scenically landscaped 100 acre-plus estates on urban peripheries, ICAR and the country’s 71 government agriculture universities manage model farms with impressively high yields, but maintain minimal connect with rural communities and farmers – Dilip Thakore

The recent turmoil in the Rajya Sabha on September 20, the upper house of Parliament, when three Bills, viz Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020, the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020 and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Bill, 2020 were passed by a voice vote amidst vociferous protests by several opposition parties, has belatedly brought the country’s agriculture sector into media and societal spotlight.

The objective of the three Bills is to direct the beneficial winds of liberalisation and deregulation across the country’s vast and varied rural hinterland to fulfil a promise made in the Election Manifesto 2019 of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to double farmers’ incomes by 2022. According to several respected political pundits, this assurance substantially contributed to the BJP/NDA coalition government being returned to power at the Centre with a two-thirds majority in the Lok Sabha (the more powerful lower house of Parliament) in General Election 2019.

Incontrovertibly, socio-economic conditions in rural India are appalling. It’s a telling statistic that although 60 percent of 21st century India’s 1.30 billion citizens reside in the rural hinterland, they contribute a mere 16 percent of the country’s GDP (gross domestic product) estimated at Rs.227 lakh crore in 2019-20. Per capita income in rural India is a mere Rs.40,925 against Rs.98,435 in urban India. Worse, according to the recently released Human Capital Index of the World Bank, 35 percent (142 million) of under-5 children in India — the great majority in rural India — are stunted and “likely to suffer lifelong cognitive disability”.

Quite obviously, there was a fundamental flaw in the detailed plans of the Soviet-inspired high-powered Planning Commission (estb.1950) which produced 13 voluminous five-year plans to ensure the balanced growth of the Indian economy for 65 years until the commission was mercifully abolished in 2014. In retrospect, it’s clear that as in communist Soviet Union and China, savings of the rural citizenry of post-independence India were canalised into giant public sector enterprises (PSEs) which were naively expected to generate vast surpluses for investment in public education, health and rural infrastructure.

Tragically, PSEs managed by business-illiterate bureaucrats and government clerks never produced the budgeted surpluses with the result that contemporary India is among the world’s most under-educated, medically under-served countries with a desperately poor rural citizenry. These infirmities of the Indian economy have been brought into sharp focus during the current Covid-19 pandemic, highlighting that the country has neither the intellectual capital nor economic resilience to effectively combat the sweeping virus devastating Indian society.

Widespread rural poverty which prompts mass annual migration of rural youth to work in urban India in humiliating conditions and live in Dickensian squalor, has exposed the problems-solving inadequacy of central planners and the neta-babu brotherhood, which the industry liberalisation and deregulation of 1991 notwithstanding, continues to micro-manage the economy. Persistent rural poverty and backwardness has also raised questions about the competence and contribution of the apex-level Delhi-based Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR, estb.1929) and the country’s 71 agriculture universities towards modernising Indian agriculture and raising living standards in rural India. Curiously, ICAR and vice chancellors and faculty of the country’s agriculture universities have maintained a deafening silence on the issue of forced march of an estimated 10 million migrant labour to their village homes after they were thrown out of their jobs and modest lodgings and all public transport was shutdown at four hours’ notice on March 24 by the Central government following the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic. Nor have any of them joined the public debate on the three controversial agriculture reform Bills passed by Parliament last month which have divided the country.

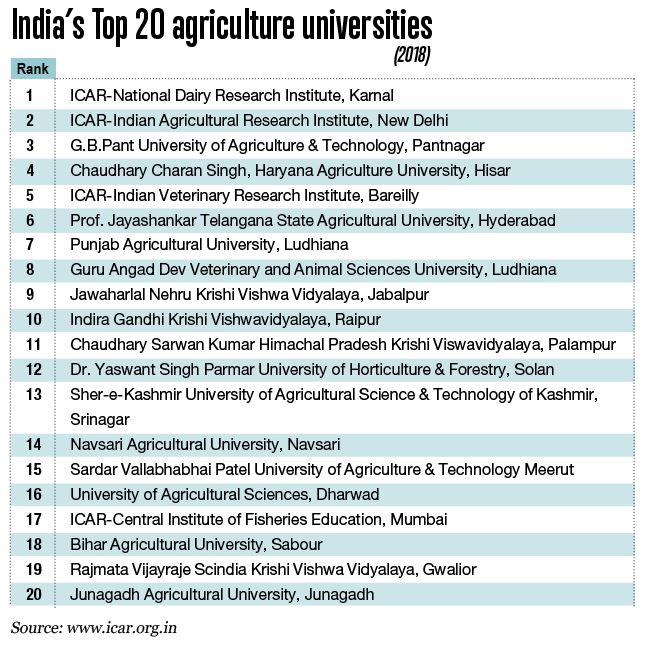

The popular perception of ICAR and its affiliated 71 government agriculture universities is that they are ivory tower institutions filled with ritually qualified kith and kin of the neta-babu (politician-bureaucrat) brotherhood which has hijacked post-independence India’s economy. These universities are established on huge, beautifully landscaped 100-acres-plus estates on urban peripheries, and pay their faculty very comfortable Seventh Pay Commission salaries and perks. Typically, they are defined by huge establishment expenses, low tuition fees for students, and have large research budgets. Moreover, all of them manage model farms sustained with best fertiliser and pesticide inputs and impressively high yields, but maintain minimal connect with rural communities and farmers. Their ‘extension services’, i.e, application of research and laboratory know-how in wider fields beyond their campuses is their Achilles heel.

This ivory tower mentality and lack of accountability — except to their political masters — is graphically manifested by the obstinate refusal of Dr. Trilochan Mohapatra, chairman of ICAR, described — on its admittedly informative and detailed website (www.icar.org) — as an “autonomous organisation under the Department of Agricultural Research and Education (DARE), Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India” and “the apex body for co-ordinating, guiding and managing research and education in agriculture including horticulture, fisheries and animal sciences in the entire country,” to accord the favour of an interview over the telephone or Zoom, or even reply in writing to six questions relating to the country’s agriculture education and research system and its role in the promised agriculture revolution.

This ivory tower mentality and lack of accountability — except to their political masters — is graphically manifested by the obstinate refusal of Dr. Trilochan Mohapatra, chairman of ICAR, described — on its admittedly informative and detailed website (www.icar.org) — as an “autonomous organisation under the Department of Agricultural Research and Education (DARE), Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India” and “the apex body for co-ordinating, guiding and managing research and education in agriculture including horticulture, fisheries and animal sciences in the entire country,” to accord the favour of an interview over the telephone or Zoom, or even reply in writing to six questions relating to the country’s agriculture education and research system and its role in the promised agriculture revolution.

Numerous phone calls and emails only resulted in replies that these requests would be “put up” to the director. This contempt for the public and media is in sharp contrast to the abject sycophancy of Mohapatra who never fails to attach the description “honourable” every time he refers to Union agriculture minister Narendra Singh Tomar and prime minister Narendra Modi and gives substance to the common complaint that extension officials of ICAR are inaccessible and entertain barely concealed contempt for farmers they are obliged to counsel and advise.

Unsurprisingly Dr. Mohapatra, an alumnus of Ravenshaw College, Cuttack and Orissa University of Agriculture and Technology, appointed director-general of ICAR in 2016, is more than satisfied with the contribution of ICAR to development of Indian agriculture, which according to him is going great guns. In the 16-page ICAR annual report 2019-20, Mohapatra writes: “ICAR is the harbinger of Green Revolution in India and instrumental in subsequent advances in agriculture sector in India through its significant achievements in research, extension and education. It has empowered the country to increase the production of foodgrains by 5.4 times, horticultural crops by 10.1 times, fish by 15.2 times, milk 9.7 times and eggs 48.1 times, since 1951, thus making a visible impact on the national food and nutritional security.

Unsurprisingly Dr. Mohapatra, an alumnus of Ravenshaw College, Cuttack and Orissa University of Agriculture and Technology, appointed director-general of ICAR in 2016, is more than satisfied with the contribution of ICAR to development of Indian agriculture, which according to him is going great guns. In the 16-page ICAR annual report 2019-20, Mohapatra writes: “ICAR is the harbinger of Green Revolution in India and instrumental in subsequent advances in agriculture sector in India through its significant achievements in research, extension and education. It has empowered the country to increase the production of foodgrains by 5.4 times, horticultural crops by 10.1 times, fish by 15.2 times, milk 9.7 times and eggs 48.1 times, since 1951, thus making a visible impact on the national food and nutritional security.

The ICAR has played a pivotal role in promoting excellence in higher education in agriculture, while also engaging in innovative areas of science and technology development by its research, which is acknowledged nationally and internationally. In the recent years, ICAR has been playing an important and proactive role in agricultural technology dissemination through its strong network of Krishi Vigyan Kendras and supporting farmers in all possible ways. ICAR is sturdily contributing towards the efforts and initiatives of government to double the farmers’ income by 2022 by its research on farming systems, policy inputs and coordination with state agencies.”

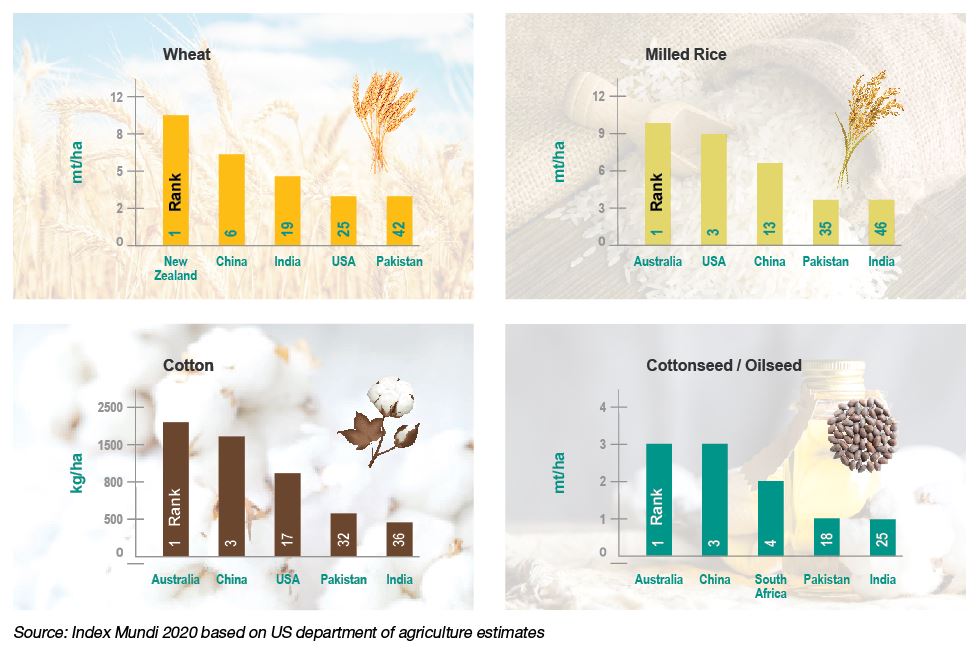

Ex facie these huge increases in India’s production of foodgrains, horticulture produce and livestock is impressive. But it’s important to bear in mind that the timeframe adopted by Mohapatra is seven decades, during which the country’s population has risen 3.5 times, that rural India has not only many more mouths to feed, but 7 times as many hands to work with new, mind-boggling technologies of Industrial Revolution 4.0. Therefore, the more important metric to measure the progress of Indian agriculture during the past seven decades is per-hectare yields of farm produce. By this metric, productivity of India’s over 400 million farmers is abysmal. Although in 2019-20, India’s wheat production totalled 106 million tonnes, on the Index Mundi 2020 based on US department of agriculture estimates, India ranks #19 worldwide with an average yield of 4 mt/h below China #5 (6 mt/h), Egypt #8 (6), in a table topped by New Zealand #1 (9 mt/h).

In the league table of milled rice productivity, India’s farmers fare worse. They are ranked #46 with an average yield of 4 mt/h against top-ranked Australia’s 10 mt/h. Surprisingly, India is ranked below Bangladesh #28 and Pakistan (35). Likewise on the millet (#39) and cotton (#36) productivity league tables as well, India is an also-ran. On the cotton productivity league table of Index Mundi, India is ranked #36 with 496 kg/h. In the table headed by Australia (2,056 kg/h), China is ranked #3 (1,748 kg/h) while India is ranked below Egypt, Pakistan and Bangladesh among others (see table).

For the near rock-bottom factor productivity of India’s majority farming community, surely some — if not all — of the blame can be levelled against ICAR and affiliated agriculture universities whose graduates and/or faculty have failed to disseminate best farming nostrums and practices within the population.

“ICAR and India’s agriculture universities played a major role in enabling the Green Revolution of the 1970s when India surprised the world and successfully began the process of making the country self-sufficient in foodgrains production. But after that, they focused for too long on developing different strains of rice and wheat and did insufficient research in less water-intensive crops such as sorghum and millets. Moreover after the food crisis was over, ICAR and most state government universities began to experience government funding shortages which private sector companies have not been able to bridge.

“ICAR and India’s agriculture universities played a major role in enabling the Green Revolution of the 1970s when India surprised the world and successfully began the process of making the country self-sufficient in foodgrains production. But after that, they focused for too long on developing different strains of rice and wheat and did insufficient research in less water-intensive crops such as sorghum and millets. Moreover after the food crisis was over, ICAR and most state government universities began to experience government funding shortages which private sector companies have not been able to bridge.

Since then, ICAR and the universities have gradually lost their dynamism of the Green Revolution years , their interface and communication with the public has become poor and their extension services, i.e farm and field visits, have declined,” says Dr. Arindam Banerjee, an alumnus of Presidency College, and JNU, Delhi, and currently associate professor of agriculture economics at Ambedkar University, Delhi.

Banerjee’s assessment of ICAR and the country’s 71 agriculture universities is couched in measured academic language. Yet the plain truth as your correspondent discovered while trying to reach ICAR director-general Trilochan Mohapatra and vice chancellors of several government agri universities is that they have evolved into typical bureaucratic government organisations with no concept of public accountability. All attempts to interview them telephonically or to get them to reply to written questions were blocked by retinues of timorous personal assistants and secretaries.

“Despite their huge budgets funded by the public, agriculture universities are highly structured government bureaucracies with strong kiss-up-kick-down cultures. Their officials and faculty are not interested in extension work and have no time for the public. I remember making a request to officials of the ICAR-Institute of Horticulture Research, Bangalore, for an extension officer to examine a guava canker on my orchard farm. But they demanded a sum of Rs.3,000 per visit, which I could ill-afford, because of the chronically low prices for horticulture produce mandated by strong cartels within APMC centres in Bangalore,” recalls Anil Thakore, a highly-qualified alumnus of the Royal College of Agriculture, Cirencester (UK) and College of Tropical Agriculture, University of West Indies, who tried to profitably manage a 20-acre dairy and horticulture farm on the outskirts of Bangalore from 1974-1982 before giving up farming in India as “an inherently unviable proposition”.

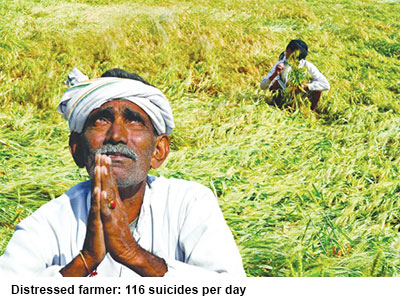

Clearly the stark reality is that there is a massive crisis in Indian agriculture — 116 farmers take their own lives every day countrywide — because of unremunerative prices for agri produce and total lack of rural infrastructure such as motorable roads, warehousing and cold-chain facilities, logistics and downstream food processing industry.

Clearly the stark reality is that there is a massive crisis in Indian agriculture — 116 farmers take their own lives every day countrywide — because of unremunerative prices for agri produce and total lack of rural infrastructure such as motorable roads, warehousing and cold-chain facilities, logistics and downstream food processing industry.

But this reality doesn’t seem to have made any impact in the Punjab Agriculture University (estb.1963) which sprawls over 494 hectares (ha) in Ludhiana and 1,793 ha off-campus (annual budget: unknown). On the university’s website, vice chancellor Dr. Baldev Singh Dhillon is described as an “internationally acclaimed scientist in the field of plant breeding and genetic resources” under whose watch “the state achieved the highest productivity (>12 mt/ha) in 2017-18”. Nevertheless, this worthy couldn’t find the time to respond to a written questionnaire despite over a dozen calls and emails addressed to him in the public interest.

Nevertheless, ICAR and its affiliated agriculture universities have their defenders. According to Harish Damodaran, national rural affairs and agriculture editor of the Indian Express, although their “communications and public interface could be better”, the contribution of ICAR and India’s agriculture universities to the national development effort has been “greater than the IITs and IIMs combined”. “Over the past seven decades despite not being well-funded, they have not only made the ship-to-mouth India of the 1960s which was faced with the real prospect of mass starvation, self-sufficient in food grains and horticulture produce, they have also developed a large number of seeds and strains suitable for all soils and terrains.

Nevertheless, ICAR and its affiliated agriculture universities have their defenders. According to Harish Damodaran, national rural affairs and agriculture editor of the Indian Express, although their “communications and public interface could be better”, the contribution of ICAR and India’s agriculture universities to the national development effort has been “greater than the IITs and IIMs combined”. “Over the past seven decades despite not being well-funded, they have not only made the ship-to-mouth India of the 1960s which was faced with the real prospect of mass starvation, self-sufficient in food grains and horticulture produce, they have also developed a large number of seeds and strains suitable for all soils and terrains.

The primary duty of faculty in these institutions is to teach and research which they have discharged admirably. Although all the universities offer extension services, it’s not the duty of scientists to provide field services. Transferring lab research to farmers’ fields is the job of agriculture ministries of the states. For the widespread distress, farm suicides and low productivity and prices of farm produce, the fault is of government policies not universities,” says Damodaran, who has 29 years of experience at PTI, Hindu Business Line and Indian Express.

Aspirited defence of ICAR and state agriculture universities is also advanced by Dr. M.G. Chandrakanth, an alum of the University of Agriculture Sciences (UAS), Bangalore, and University of California at Berkeley, former professor of agricultural economics at UAS and former director (2016-20) of the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore (ISEC, estb.1972).

Aspirited defence of ICAR and state agriculture universities is also advanced by Dr. M.G. Chandrakanth, an alum of the University of Agriculture Sciences (UAS), Bangalore, and University of California at Berkeley, former professor of agricultural economics at UAS and former director (2016-20) of the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore (ISEC, estb.1972).

“For the younger generation it’s impossible to imagine the food insecurity that the country was suffering in the early years of the Green Revolution. Under the leadership of great scientists including Union agriculture minister C. Subramaniam, M.S. Swaminathan, American agronomist Norman Borlaug and Dr. M. Mahadevappa working in ICAR and state agriculture universities, the production of food grains was raised from 50 million tonnes in 1950 to 300 million tonnes currently, a monumental national effort centred in India’s agriculture universities which continue to do excellent teaching and research. Indeed thanks to the new strains of rice evolved by them, India is currently the world’s #1 high-quality rice exporting country,” says Chandrakanth.

With reference to the low per-hectare yields of Indian farmers and widespread poverty in rural India, Chandrakanth has ready explanation. According to him, per-hectare league tables don’t reveal the ground reality that India’s farmers grow and harvest two-three crops per year on the same land and that per-hectare usage of fertilisers and pesticides is substantially lower than in most countries. “The prime causes of rural poverty in India are hostile cartelised markets, too many intermediaries and poor credit dispensation forcing dependence on usurious money-lenders, inadequate storage and cold chains which force distress selling. All these are policy-related problems totally unrelated to our agriculture universities. It’s also pertinent to note that 65 percent of rural India is rain-dependent with farmers receiving only 30-35 days of rainfall on average. The causes of rural distress are policy failures, especially in irrigation and beyond the remit of India’s agriculture universities,” argues Chandrakanth.

While there is undoubtedly considerable merit in the arguments advanced by Damodaran and Chandrakanth that India’s 71 universities under the ICAR umbrella have substantially contributed towards transforming the ship-to-mouth Indian economy of the 1960s into a food surplus nation, it’s also arguable that they haven’t sufficiently discharged their advisory role in policy formulation. Admittedly, the teaching and research record of these academies is commendable, but over the years India’s agriculture universities have transformed into giant white collar bureaucracies with discernible aversion to extension work.

Also read: Agriculture Bills need careful scrutiny

According to some agriculture economists, the universities’ extension work which was exemplary in the heyday of the Green Revolution has suffered because of the abolition in the new millennium of the cadre of university gram sevaks engaged in extension and handholding last mile duties in farmers’ fields. With the autonomy of ICAR and state universities wholly eroded by successive governments at the Centre and in the states, this “big mistake” of institutional interference went unprotested. Since then, ICAR’s 101 institutes and the country’s 71 state agriculture universities have transformed into islands of teaching and research excellence increasingly isolated from their rural communities.

Against the backdrop of Parliament having enacted three reportedly revolutionary Acts which promise to revolutionise Indian agriculture, in the pages following we present interviews with leaders of three of India’s most respected agriculture universities in the hope that they will shed light on the root causes of the prolonged malaise in rural India, which grudgingly hosts two-thirds of the country’s population.

https://www.educationworld.in/tamil-nadu-agricultural-university-coimbatore/

https://www.educationworld.in/institute-of-rural-management-anand/

Add comment