India’s mighty medical education mess

According to the latest data of the Union education ministry, 23,000 Indian students are reading medicine in China, 18,000 in Ukraine, 16,000 in Russia, and 15,000 in the Philippines. Every year, thousands of aspiring medicos are driven out of the country because of a huge demand-supply imbalance in medical education, writes Summiya Yasmeen

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24 and continuing warfare between the two neighbour nations now in its fifth month, has not only devastated Ukraine and slowed the global economy, it has also torpedoed the higher education of 18,000 Indian students enrolled in medical schools across Ukraine. As the Russian military rained rockets on Ukrainian cities, television and social media platforms beamed photos and interviews with Indian students appealing for evacuation by the Indian government. By mid-March, these 18,000 students were evacuated under Operation Ganga.

Escape from the ravages of war provided the students only temporary relief as they returned to an uncertain future back home. With a ceasefire unlikely in the near future and no guarantee of return to their universities, 100 days on, the evacuated students are making frantic appeals to the Union government’s health and education ministries and National Medical Commission (NMC) to allow them to continue their studies in Indian medical colleges, to little avail.

Meanwhile, even as the fate of the evacuated students hangs in the balance, a question being debated by academics, civil society activists and the public is why such a large number of Indian students were obliged to study medicine in Ukraine, which most people can’t locate on the world map. The answer is provided by Shekharappa Gyanagoudar, a retired paper mill employee residing in Karnataka’s Haveri district. On March 1, his son Naveen Shekharappa, a fourth-year medical student at Kharkiv National Medical University, was killed in a Russian rocket attack.

According to Gyanagoudar, although his son averaged 97 percent in his class XII boards, his score in the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) — the sole pan-India test introduced in 2014 for admission into the country’s medical and dental colleges — was 13 less than the qualifying score for admission into Karnataka’s 17 heavily subsidised government medical colleges. “For a seat in a private medical college, the total expense is Rs.1 crore over five years, including donation. The same education in Ukraine costs Rs.7 lakh per year,” Gyanagoudar told reporters.

Naveen Shekharappa was one of tens of thousands of aspiring medicos driven out of the country because of India’s huge demand-supply imbalance in medical education. According to latest data of the Union education ministry, 23,000 Indian students are reading medicine in hostile China, 18,000 in Ukraine, 16,000 in Russia, and 15,000 in the Philippines. These students had no option but to flee abroad because of India’s grossly inadequate medical education capacity.

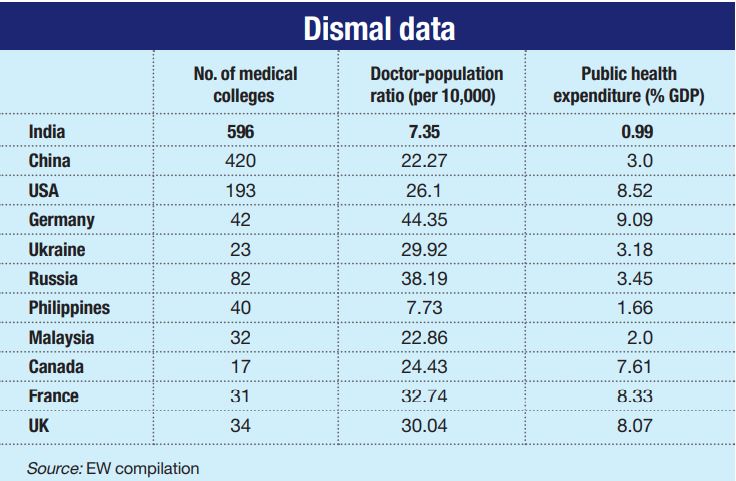

Paradoxically, although India hosts the highest number of medical colleges worldwide — 596 — they offer a mere 88,120 seats annually for undergrad medical education. Conversely, China’s 420 colleges offer 286,000 seats. Unsurprisingly, India has a doctor-population ratio of 1:1,456 (WHO recommendation 1:1,000), one of the worst worldwide. Behind this skewed ratio is a story of open, uninterrupted and continuous ideological confusion, poor planning, massive corruption and callous official disregard for the education and health of the world’s largest child and youth population.

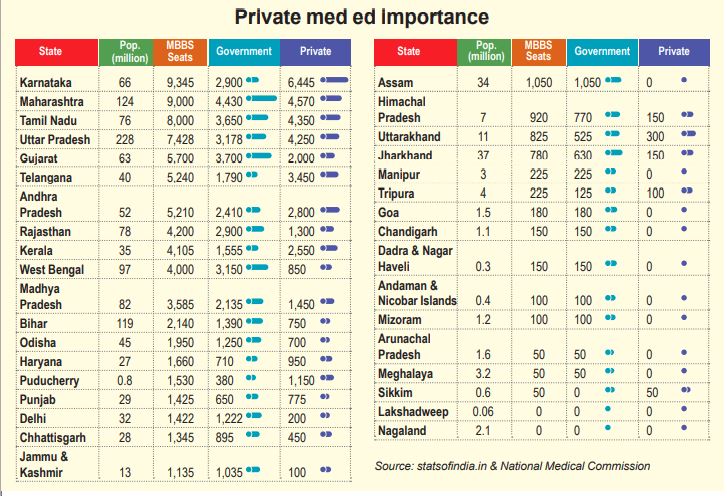

In 2021, 1.5 million students wrote the NEET. Of them, 870,000 cleared it and competed for 88,120 seats in 275 government and 321 private medical colleges — an acceptance rate of less than 5 percent with 19 students competing for every seat. If one further splits available seats into government (42,000) and private (46,120), the competition is more intense because for middle and lower middle class students, the real battle is for government college seats which provide highly subsidised medical education. Tuition fees in the country’s over-subsidised government medical colleges range from a paltry Rs.970- 1.11 lakh per year (cf. Rs.18-30 lakh per year in private colleges and deemed universities).

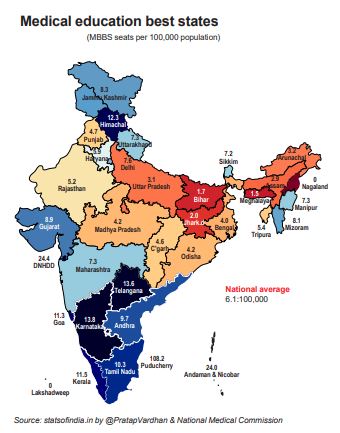

Moreover, there’s a conspicuous regional imbalance in the availability of medical colleges and seats. The six socio-economically advanced states of peninsular India (Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Telangana, Puducherry and Andhra Pradesh) and the western state of Maharashtra host 60 percent of medical colleges in the country, while the populous Hindi belt states are starved of them. The southern states and Maharashtra with an aggregate population of over 400 million host 302 colleges which offer 42,000 seats per year. Meanwhile, the two most populous states — Uttar Pradesh (220 million) and Bihar (104 million) — have 71 medical colleges offering only 9,168 MBBS seats annually.

“The one major problem that encapsulates all others in medical education is that only 88,120 MBBS seats are on offer every year. That’s far smaller than demand and social need. An estimated 40 percent of these seats are in government colleges where tuition fees are heavily subsidised by Indian taxpayers, while the remaining 60 percent are in private colleges where the fee ranges between Rs.18-30 lakh per year. The scarcity of seats generates huge demand for coaching institutes that help students to top the highly competitive NEET,” says Pranay Kotasthane, deputy director of the Takshashila Institution, a Bengaluru-based public policy think tank.

This demand-supply imbalance and middle class aspiration for the prized medical degree at all costs, have coalesced to create, drive and sustain the Rs.126430 crore NEET coaching industry. Secondary school-leavers are herded into offline and online coaching classes to drill and skill them to top NEET and secure that elusive medical seat in the country’s minuscule number of over-subsidised government medical colleges.

Anmol Pradhan, a third-year-student of Damylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, who was evacuated from Ukraine in March, recalls being packed off to Kota (Rajasthan) — the entrance exams coaching capital of India which hosts 150-200 institutes charging between Rs.1.2-2 lakh per year — in class XII because his parents were hell-bent on him qualifying as a doctor. “But I couldn’t cope with the stress of the Kota factory and returned home to Mumbai. Despite the personal turmoil that I faced during my class XII, my NEET rank wasn’t bad at all. But government colleges admit only the top 2 percentile of NEET candidates. On the other hand, private medical colleges charge exorbitant tuition fees. My father, a banker by profession, calculated down to the last rupee and figured that a five-year MBBS programme would cost him Rs.1 crore in a private medical college in India. On the other hand, a five-year medical degree in Ukraine is 40 percent cheaper at Rs.60 lakh and Ukraine medical degrees are recognised by the Indian Medical Council, in Europe and the UK. Unfortunately, the Covid pandemic shut down classes indefinitely, then came the Russian invasion,” laments Pradhan.

Similarly, Sahil Aneja, a third-year medical student at Lviv University, has two recurring nightmares – one of his miraculous escape to India via Poland and the other about his uncertain future. “My parents have already sacrificed a lot to pay for my medical education. I can’t give up medicine suddenly and start looking at switching to other streams. Where do students like me go from here? I have no hope that the corrupt and elite medical education system that drove us out of the country, will accommodate us and save my future,” says Aneja.

Informed monitors of India’s lopsided medical education system blame the Medical Council of India (MCI, estb.1933), the sole regulator of medical education countrywide for 86 years until it was disbanded in 2019 and replaced by the National Medical Commission (NMC), for this mess which has driven thousands of Indian students to foreign countries in desperate search for medical qualifications. Established in pre-independence India under the Indian Medical Council (IMC) Act, 1933, MCI’s initial brief was to prescribe uniform standards for allopathic medical education and to license medical practitioners.

The IMC Act of 1933 was repealed in 1956 and replaced with the Indian Medical Council Act (amended in 1964, 1993, 2001 and 2011) which expanded MCI’s powers, investing it with the authority to license medical colleges and their degrees; set academic standards, prescribe faculty qualifications; inspect colleges to evaluate infrastructure adequacy; approve new study programmes and regulate student intake in every college. The wide discretionary powers invested in MCI inevitably opened the floodgates of corruption, especially with the demand-supply gap for medical education widening and private education providers (aka edupreneurs) stepping forward to breach the gap.

MCI’s descent into corruption, cronyism and rent-seeking hit national headlines when Ketan Desai, an obscure professor of urology at B.J. Medical College, Ahmedabad, was elected MCI president in 1996. During his five-year tenure (1996-2001), Desai reportedly amassed a huge fortune by brazenly misusing MCI’s discretionary powers to license, inspect and regulate medical colleges. On November 23, 2001, the Delhi high court convicted him for accepting a bribe of Rs.65 lakh from two businessmen for dispensing favours to medical colleges in Pimpri and Ghaziabad, and ordered his removal from presidency of MCI. The court also directed CBI to probe and prosecute Desai under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988.

Desai’s “special clout with concerned (sic) government officials” ensured that the CBI investigation didn’t make much headway. In 2005, the bureau filed a closure report in the case stating that the Rs.65 lakh taken by Desai was “goodwill” money. Four years later in 2009, Desai who had packed the MCI board with cronies and was driving the council from the back seat, was re-elected president of MCI. But a reported fall-out with his protectors (i.e, politicians and bureaucrats) in the Central government resulted in his being re-arrested a year later (2010) and charged with corruption. In May 2010, the newly re-elected Congress-led UPA-II government dissolved MCI and constituted a Board of Governors (BoG) to run it for a year pending the enactment of a new law to replace the council.

But that law was not drafted until 2019 when the BJP/NDA 2.0 government was returned to power at the Centre. Soon after, the BJP government dissolved MCI and a year later on September 25, 2020, both houses of Parliament passed the National Medical Commission Bill, 2020. Welcoming the National Medical Commission (NMC), prime minister Narendra Modi said: “We are transforming the entire medical education and healthcare sector. The National Medical Commission will bring great transparency and also rationalise norms to set up new medical colleges. It will also improve the quality and availability of human resources in this sector.” Subsequently, he also announced the promotion of 15 new AIIMS (All India Institutes of Medical Sciences) at a cost of Rs.2,000 crore each.

Since then three years on, NMC is yet to announce any radical initiatives to address the root problems of inadequate capacity, discretionary licensing, red tape and inspector raj. Instead, its two major announcements have been introduction of NEXT (National Exit Test) — a licentiate exam which all medical graduates from India and abroad are obliged to clear to practice medicine in India — and tighter regulation of private medical colleges and private deemed universities providing medical education. On February 3, NMC directed all private medical colleges and deemed universities to charge 50 percent of their students the (highly subsidised) tuition fees levied by government medical colleges from the academic year 2022-23 onward. A month later (March 7), prime minister Modi justified this populist NMC proclamation. “A few days back, the government has taken another big decision which will benefit the poor and middle-class children. We have decided that half the seats in private medical colleges will be charged at par with government medical colleges,” he tweeted.

Self-evidently, against the backdrop of a widening demand-supply gap in medical education, this populist proclamation was ill-advised because it will discourage private investment in medical education. The infrastructure norms prescribed by NMC for greenfield medical colleges are formidable and capital intensive. Neither domestic nor foreign edupreneurs are likely to be enthused by the prospect of admitting half their students at artificially lowered government college fees.

“NMC promises radical change and transformation in medical education. But although medical education has a new structure, the nuts and bolts are the same. Its positive initiatives are the establishment of autonomous boards to draw up contemporary competency-based undergraduate and postgrad curriculums and an assessment and ratings board. Yet on the larger issues of liberalising rules and regulations for promoting new colleges, increasing student intake and most important, addressing the problem of severe faculty shortages, it needs to do more. Its regulation capping fees for 50 percent of seats in private colleges and deemed universities is a disincentive which several private colleges have already challenged in the courts. If NMC truly wants to transform medical education, it must focus on easing the stranglehold of age-old regulations and give private medical institutions financial and administrative freedom,” says Dr. Sambit Dash, assistant professor, biochemistry & genetics at the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), and a columnist (Livemint, The Wire, Deccan Herald) on medical education and public healthcare.

Apprehension about continuing micro-management and discretionary regulation of private medical colleges has not been allayed by NMC. Dr. Venkataramana Kandi, professor of microbiology at the Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences, Karimnagar, Telangana, cites NMC’s cancellation of 450 MBBS seats and 70 PG seats in three private medical colleges in Telangana in May for violating infrastructure standards, as a case in point. “Why couldn’t NMC monitor these colleges at the construction stage? What’s the point of cancelling seats when students have already been enrolled and the colleges are fully functional? Promoters invest large amounts to start colleges and avail bank finance to construct them. It’s not right to suddenly reduce intake capacity which throws financial calculations into disarray. NMC needs to focus on formulating rules and regulations which improve the quality of medical education and graduates, address the pressing problem of faculty shortages and provide support to faculty pursuing research,” says Dr. Kandi, who has published a paper Medical Education and Research in India: A Teacher’s Perspective (May 2022).

Although tight regulation of medical education by MCI proved a dismal failure, its successor council NMC believes greater rather than lesser regulation is the panacea for India’s medical education mess. Its fees diktat capping fees for 50 percent seats in private medical colleges as also deemed universities — the latter hitherto free of fee ceilings — is certain to discourage edupreneurs from augmenting existing capacity to bridge the demand-supply gap. For several decades, state governments countrywide have snatched quotas from privately promoted medical colleges.

Under this arrangement backed by legislation, private college managements are obliged to surrender 40-50 percent capacity to government-selected students, and provide them education at government-prescribed tuition fees. For instance in Karnataka, the state government has imposed a complicated three-tier tuition fees structure upon private medical colleges under which 40 percent of students who top NEET pay a mere Rs.1.41 lakh per year; the next 45 percent pay Rs.9.9-20 lakh and 15 percent admitted under the NRI quota pay Rs.45 lakh per annum.

Now NMC has mandated that private deemed universities providing medical education, which was hitherto exempt from this arrangement, are also obliged to reserve 50 percent of capacity for state governments at government prescribed fees.

In effect, this order nullifies the Supreme Court’s historic 13-judge bench judgement in the T.M.A. Pai Foundation Case (2002), which permitted privately promoted professional (medical, engineering) colleges to prescribe their own admission procedures (subject to their being transparent and merit-based), and levy “reasonable” tuition fees.

However, subsequently in the Islamic Academy Case (2003), a five-judge bench of the apex court whittled down the court’s earlier verdict, allowing state governments to establish admission and fees committees to supervise whether admission procedures of private professional colleges are transparent and tuition fees reasonable. This prompted private professional (including medical) college managements to buy peace by voluntarily surrendering 40-50 percent of their seats to state governments at government-mandated tuition fees.

The inevitable consequence of private college managements being forced to allocate 40-50 percent of capacity at less than 10 percent of the actual cost of medical education, is capitation fees. Unable to provide and upgrade infrastructure facilities, pay faculty salaries (which range between Rs.2-3 lakh per month) and maintain mandatory teaching hospitals, managements of private medical colleges have been driven to demanding capitation/donation fees (repeatedly banned by the Supreme Court) from students admitted under the management/NRI quota. In February 2021, the income tax department raided several medical colleges across Karnataka and reportedly seized unaccounted cash of Rs.400 crore allegedly collected as donations.

“Forced donations are collected through a network of agents employed by trustees and promoters of private medical colleges. The search operation resulted in detecting incriminating evidence regarding cash-for-seat malpractices for admission to MBBS, BDS and PG seats in the form of notebooks, handwritten diaries, excel sheets containing the details of cash received from students/brokers for admission in these colleges for various years,” says a statement by the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) of February 18, 2021.

On May 19, 2022, the Supreme Court again directed government to act against medical colleges levying capitation fees and issued directions to set up an online public portal under its aegis where students can report/post any information about private medical colleges demanding capitation fees. The apex court seems oblivious that tuition fees regulation and interference in admission processes of private medical education institutions by government has resulted in sky-high fees for management quota students to cross-subsidise government quota students and the capitation fees phenomenon.

Moreover, promoting a medical college in India is an expensive, capital intensive endeavour. According to estimates, it costs edupreneurs anywhere between Rs.250-400 crore to establish a greenfield medical college. Preconditions mandated by NMC include minimum 20 acres of land (relaxed to 10 acres in metros) and a 300-bed attached hospital, which should be functional for at least two years at the time of application for promoting a new medical college. In addition NMC mandates differing infrastructure requirements for varying batches of student intake (50, 100, 150, 200, 250).

Dr. Devi Shetty, renowned cardiologist and chairman of Narayana Health City, Bengaluru, blames these burdensome stipulations to start and run medical colleges for the chronic capacity shortage and systemic corruption. “In India, it costs Rs.400 crore to build a medical college. The stipulated conditions are ridiculous. In the Caribbean, 35 medical colleges are training doctors for the US in 50,000 sq. ft rented premises in shopping malls with students interning in public hospitals. A medical college with 140 faculty is permitted to teach 1,000 students, not 100 as prescribed by NMC. In India, we have made medical education an elitist affair… this country requires liberation of medical, nursing and paramedical education,” says Dr. Shetty (see www.youtube.com/watch?v=IuMCGjjwyRI).

Curiously, the great Indian middle class which has substantially benefited from the industry liberalisation and deregulation initiative of 1991, seems unable to apply its logic to liberalisation of India’s over-regulated education system suffering egregious demand-supply imbalances and endemic corruption.

“Unreasonable government regulations are preventing capacity expansion in medical education. Regulation compliance categories for admitting 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 students differ. The number of attached hospital beds, examination halls etc, all need to increase correspondingly before student intake is increased. Exhorting private investors to set up new colleges is not enough; they respond to incentives. They will expand capacity to admit more students only when unreasonable restrictions are removed. Citizens also have a role to play. Debates on healthcare services quickly acquire moralising undertones — “commercialisation” is evil and economic reasoning is clouded. The fear of poorly trained doctors misdiagnosing patients is used to dismiss any solution for liberalising medical education. Addressing this concern requires strengthening regulation of medical practice, not smothering medical education,” says Pranay Kotasthane, deputy director of the Takshashila Institution (quoted earlier).

Quite clearly with arguably the worst doctor-population ratio (1:1,456) of any major country worldwide and bankrupt official treasuries, India urgently needs a regulatory environment that encourages private sector initiatives and capacity expansion to meet the growing shortage of human resources in the health sector. Simultaneously, the Union and state governments need to mobilise resources for investment in public health facilities and to build adequate healthcare infrastructure, especially in rural India.

The silver lining of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is that the sorry plight of Indian medical students has exposed the infirmities of India’s medical education system which forces Indian students to sign up with medical schools in strange and often hostile territories to acquire the qualifications necessary to serve the sick and ailing. This situation is untenable. Root-and-branch reform of medical education is long overdue. Band-aid solutions won’t revive it.

With inputs from Abhilasha Ojha

Read: Indian Embassy in Kyiv is “helpless” &”powerless”: Ukraine-returned medical student

Add comment