Unemployed graduates: reckless capacity expansion outcome

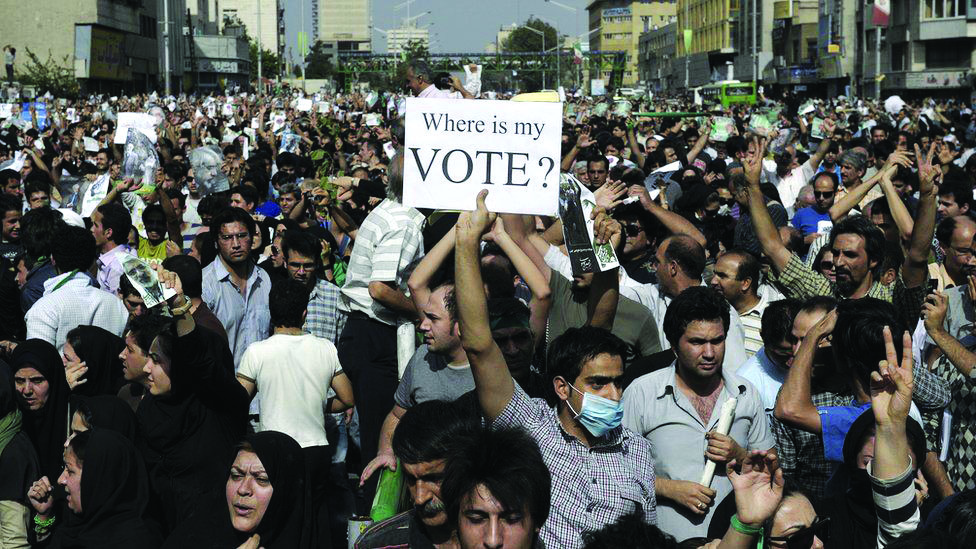

Teheran’s past policies of allowing Iran’s higher education sector to “blindly develop” to absorb students facing a tough jobs market have exacerbated current high rates of graduate unemployment. According to figures recently released by the Statistical Center of Iran, roughly one million university graduates in the country are currently unemployed, making up 37 percent of the total unemployed population at a time of soaring inflation.

While academics expressed reservations about the accuracy of the official figures, they agreed the situation is concerning. Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou, assistant professor of economics at American University, says job prospects have not been helped by the recent proliferation of higher education institutions. “The government has allowed for more and more private universities to come to existence to absorb more and more of the unemployed youth and delay their entrance into the labour market — basically kicking the can down the road,” he says.

This has made the labour problem worse, he continues, with many graduates underemployed: not having enough paid work or taking a position that doesn’t make full use of their education — or both. The higher education policy has had “unintended consequences” for the government, which faces the more difficult task of satisfying university-educated youth with high aspirations than of accommodating high school graduates, he notes.

Roohola Ramezani, a researcher in Iranian studies at the IFK International Research Center for Cultural Studies in Vienna, agrees. “Over certain periods in the past, higher education has been blindly developed to postpone the unemployment crisis. So the unemployment is partly transmitted from a less to a higher-educated population.” If the current trend continues, he says, it will lead to Iran’s “higher education bubble” bursting as more people realise that a university degree does not guarantee them a job.

Women fare much worse than men in the current situation: about 70 percent of female graduates are unemployed, almost three times the rate of male graduates (25 percent), according to official statistics. Academics say this has been a long-lasting problem tied to traditional gender roles — with women tasked with more domestic duties and with families sometimes not permitting their daughters to work — and to discrimination in hiring.

“With the new policies of (promoting) population (growth) and childbearing, I think the gender gap might get bigger,” says Dr. Ramezani.