Under s. 12 (1) (c) of the RTE Act, children of poor households (with incomes below Rs.3.5 lakh per year in Karnataka) had the chance to avail free-of-charge class I-VIII education in upscale private, non-minority schools in their neighbourhood. Under this Central government legislation, all private schools were obliged to reserve 25 percent capacity in class I for poor children (certified by local education officers) and retain them until completion of class VIII. On their behalf, the State is obliged to reimburse tuition fees, but only to the extent of the average expenditure per student incurred by state governments in their own schools (Rs.8,000-16,000 per year). In 2012 in Society for Unaided Schools of Rajasthan vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court exempted minority schools from the ambit of s.12 (1) (c).

Although s.12 (1) (c) was severely criticised by left intellectuals who dominate academia, on the ground that it would create class division and social tensions in private schools, it has proved popular with bottom-of-pyramid households in Karnataka. In 2018-19, the total number of applications received statewide under s.12 (1) (c) was 228,000 for 158,000 available seats in private schools.

However, the huge rush for the limited number of seats in private schools resulted in an embarrassing exodus from government primaries with questions raised in the state’s legislative assembly about the poor quality of education in the state’s dysfunctional 48,000 government primaries. The flight from government schools is not only to upscale schools under s.12 (1) (c) but also to low-fees levying ‘English-medium’ private budget schools whose number is estimated at 14,000 statewide. The outcome of this combined exodus is that 28,800 government primary schools with less than 10 students had to be merged with other government schools last year.

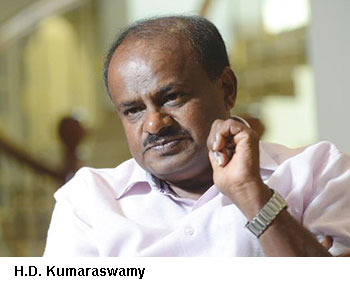

The response of the Congress-JD (S) coalition government of the state was to announce that government schools will introduce free-of-charge English-medium education as an option to parents. Although this proposal was fiercely opposed by the Kannada lobby, chief minister H.D. Kumaraswamy has held firm and is determined to inaugurate 1,000 English-medium government primaries in June.

However, on December 5 the Congress-JD (S) government amended the Rules of the RTE Act to stipulate that poor household children are eligible for admission into non-minority private schools only if there are no vacancies in neighbourhood government primaries. This amendment of the RTE Rules is likely to shrink the number of seats available to under-privileged children in private non-minority schools from 158,000 to 18,000. This amendment to the Rules, which sharply reduces the chances of underprivileged households to admit their children into upscale private schools, has angered parents, social activists and NGOs which have been aiding upwardly mobile bottom-of-pyramid families to access superior private primary education.

“We have challenged the new amendment of the state government. It is a direct contradiction of s. 12 (1) (c), which even though minority schools were exempted, has been upheld by the Supreme Court. Therefore, it’s clearly unconstitutional for the State to have introduced this amended Rule which forces thousands of our children back into dysfunctional government schools. We are sure this regressive amendment will be struck down,” says B.N. Yogananda, general secretary of RTE Students and Parents Association (RSPA), which claims it has over 1,000 members in Bangalore.

With the admission season having already begun, and the education ministry having released a 219-strong list of private schools (cf. 14,000 last year) obliged to admit s.12 (1) (c) students, heads of EWS (economically weaker section) households are in a quandary. Their best hope for sending their children to highly prized private schools is that the Karnataka high court grants RSPA a stay order against the amended Rule.

Sruthy Susan Ullas (Bangalore)