In consonance with education in general, medical education capacity building has been grossly neglected. The total number of medical colleges countrywide is a mere 462. Consequently, contemporary India has a rock-bottom (allopathy) doctor-citizen ratio of 1:1,596. Maharashtra (pop.114 million) hosts only 50 medical colleges, of which a mere 14 are promoted, owned and managed by the state government.

Since May 9, 2016 following a Supreme Court directive, all students aspiring for medical education in government and private colleges countrywide have to write the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test (NEET). This year, of the 7,000 MBBS students from Maharashtra who wrote and topped the NEET postgrad exam in January, 4,166 have applied for the postgraduate (doctor of medicine), MS (master of surgery) and diploma programmes. Against this, only 1,400 seats are available in the postgrad faculties of the state’s 14 government medical colleges. Moreover, 50 percent of these seats are reserved for out-of-state students under the All India Quota (AIQ), reducing the total number of postgrad seats in Maharashtra to 700.

However, there is a complex system of reservations for these 700 postgraduate seats as well. Government medical colleges have to reserve 50 percent of the seats (350) in postgrad programmes for scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, other backward classes and notified tribes plus another 5 percent (35 seats) for persons with disabilities and 1 percent (7) quota for orphans. Therefore, if the latest proposal of the state government to reserve 16 percent (112 seats) for Marathas under the SEBC quota, and another 10 percent (70 seats) for students from economically weaker sections is implemented, 82 percent of capacity (574 seats) will be reserved for various under-privileged castes/classes with a mere 18 percent (126 seats) of total capacity in government medical colleges — the first choice of all graduate medicos because tuition fees are heavily subsidised — available for merit students.

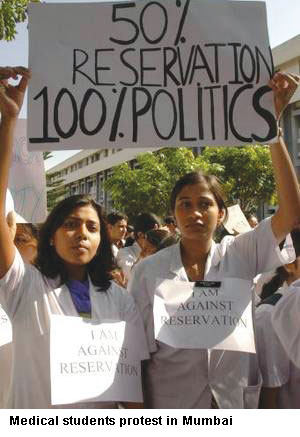

Unsurprisingly, anger is building up within the state’s middle class that their children are virtually shut out of government medical colleges which provide subsidised education. They are driven to apply to private medical colleges where tuition fees are substantially higher. For instance, the tuition fee payable by undergraduate and graduate students in Maharashtra’s 14 government medical colleges is Rs.75,000 per annum cf. Rs.7-12 lakh per year in private medical colleges.

Parents of medical students contend that the latest additional reserved quotas mandated by the state government will breach the ceiling of 50 percent for reserved categories imposed by the Supreme Court in the landmark Indira Sawhey & Ors vs. Union of India (1992). Yet it’s pertinent to note that several states, notably Tamil Nadu, breached this ceiling decades ago without any repercussions from the Supreme Court.

Dr. Pravin Shingare, former chief of Maharashtra’s directorate of medical education and research, says that the 10 percent capacity increase proposed by Union HRD minister Prakash Javadekar will also increase the quotas of all reserved categories. “Although the number of merit seats will increase, so will the seats under the reserved categories. Moreover, under a Supreme Court judgement of 1993, reserved category students who score high marks should be admitted under the merit quota. This judgement shrinks the merit pool and expands the reserved quota,” says Shingare.

On March 27, the Bombay high court declined to stay the Maratha quota for medical postgraduate admissions. Parents and students say they will now appeal to the Supreme Court to seek relief from governments who continue to pile quota upon quota in public higher education institutions to suit their vote bank calculations.

Dipta Joshi (Mumbai)