Milestones of Indian Education (1999-2024)

1999

PROBE Report. In early January 1999, a team of eminent educationists including Anita Rampal, Anuradha De, Jean Dreze and Shiva Kumar, released the Public Report on Basic Education 1999 focused on rural primary education. For the first time, it exposed the deep rot in public primary education in the populous Hindi heartland states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh). PROBE reported that 48 percent of government schools didn’t have pucca buildings; 53 percent lacked drinking water facilities; 89 percent were bereft of toilets; only 3 percent had reliable electricity supply and 33 percent of schools had only one teacher because of chronic teacher absenteeism.

PROBE 1999 also contradicted the popular myth that parents in rural India don’t want to send their children (specially girls) to school. It highlighted that an overwhelming majority of parents — 98 percent for boys and 89 percent for girl children — want their children to learn in formal schools.

EW comment. Appalled and outraged by this cruel neglect of vulnerable children, in the inaugural November 1999 issue and subsequently, EW repeatedly lauded and cited the PROBE report as the first non-government independent survey of rural schools, calling upon the Central and state governments to address and rectify the woeful condition of government primary schools by increasing government spending on public education to 6 percent of GDP as recommended by the high-powered Kothari Commission in 1967. Two years later in 2001, the NDA/BJP coalition government at the Centre launched the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan (SSA) with the specific objectives of universalisation of elementary education and strengthening the infrastructure of rural government schools. Moreover from the year 2008 coterminously with presentation of the Union Budget, in association with economist Dr. A.S. Seetharamu, former professor of education at the Institute of Social and Economic Change, Bangalore (ISEC, estb.1974), EW began presenting a resource mobilisation calculus to install a library, laboratory and lavatories in all government schools countrywide.

EW comment. Appalled and outraged by this cruel neglect of vulnerable children, in the inaugural November 1999 issue and subsequently, EW repeatedly lauded and cited the PROBE report as the first non-government independent survey of rural schools, calling upon the Central and state governments to address and rectify the woeful condition of government primary schools by increasing government spending on public education to 6 percent of GDP as recommended by the high-powered Kothari Commission in 1967. Two years later in 2001, the NDA/BJP coalition government at the Centre launched the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan (SSA) with the specific objectives of universalisation of elementary education and strengthening the infrastructure of rural government schools. Moreover from the year 2008 coterminously with presentation of the Union Budget, in association with economist Dr. A.S. Seetharamu, former professor of education at the Institute of Social and Economic Change, Bangalore (ISEC, estb.1974), EW began presenting a resource mobilisation calculus to install a library, laboratory and lavatories in all government schools countrywide.

2000

CBSE’s millennial reforms. In early January, the Delhi-based Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) — India’s largest Central school-leaving examinations board with over 15,000 upscale government and private schools affiliated with it — announced curriculum/exam reforms and a new Frontline Curriculum for the new millennium. The reforms included a shift from the marks to grading system, mandatory professional counseling for all children and group insurance for all students in affiliated schools.

EW comment. In several news reports and special report features, we critically evaluated the CBSE’s reform initiatives. In October 2000, we featured a special report titled ‘Winds of change in ICSE and CBSE’, in which we highlighted that though only ten percent of the country’s 1 million schools were affiliated with CBSE, as a standards-setting and benchmark institution it “exercises power and influence out of all proportion of its number of affiliated schools”. Since then over the past quarter century, CBSE (an autonomous subsidiary of the Union education ministry) has initiated several reforms including contemporising curriculums, introduction of the continuous and comprehensive evaluation system, inclusion of competency-based questions in exam papers, among others.

United Nations Millennium Development Goals. In September, after conclusion of a three-day Millennium Summit of world leaders in New York, the UN General Assembly adopted the Millennium Declaration and set eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). All 191 United Nations member countries (including India) committed themselves to attain the eight MDGs by the year 2015. The MDGs were (i) eradication of extreme poverty and hunger; (ii) attainment of universal primary education; ( iii) gender equality and women empowerment; (iv) reduction of child mortality; (v) improvement of maternal health; (vi) to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; (vii) ensure environmental sustainability and (viii) to initiate global partnerships for development.

EW comment. The Millennium Declaration was enthusiastically welcomed by EducationWorld. Especially the MDG to abolish extreme poverty and universalise primary education by 2015. In several news reports and editorials, we pressed upon the Central and state governments to legislate new policies and provide funding to attain these MDGs in particular.

2001

Mission SSA. Perhaps in response, in March 2001, the NDA/BJP government led by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee launched the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (Education for All) mission. Described as a ‘National Programme for Universal Elementary Education’, SSA’s main objective was to provide eight years of elementary education to all children in the 6-14 age group by 2010. An allocation of Rs.500 crore was made for SSA for 2001-2002. Over the years, SSA has evolved into the country’s flagship education programme and in 2018 was merged with other educational schemes — Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) and teacher training initiatives to form the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan.

EW comment. EW enthusiastically welcomed SSA, endorsing its objectives especially of increasing student enrollment, improving infrastructure in schools and providing teacher training. However, your editors also highlighted insufficient funding for SSA as the prime factor for its limited success in improving student learning outcomes. In a progress report titled ‘SSA: Way behind targets’ (EW May 2005), we warned that “given the sheer scale of the undertaking, and the Centre and states’ deplorable record of plan and project implementation, in all probability the SSA programme will fall well short of its ambitious targets”

86th Constitution Amendment. In November, the Constitution (Ninety-third Amendment) Act, 2001 (later renumbered to 86th), which promised to deliver the long-cherished dream of universal primary education for all children countrywide, was unanimously passed by the Lok Sabha. The Act made education a fundamental right of children and mandatory for government “to provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of six to 14 years as the state may by law determine”.

EW comment. EW cover story ’93rd Amendment: Entitlement or Illusion’ (January 2002), while heralding the landmark Act as a “historic milestone in the long struggle for etching the fundamental right to education of all children into the holy writ that is the Constitution of India,” raised the question about its effective implementation. More pertinently, it advocated that a ‘law’ to implement the Amendment should be drafted and implemented without delay.

2002

Supreme Court frees Indian education. In a historic majority judgement in the TMA Pai & Ors vs State of Karnataka & Ors delivered in October, a full 11 judges bench of the Supreme Court by a 6-5 majority affirmed the right of private unaided (financially independent) professional education colleges to regulate admissions, determine fee structure and administer their institutions with minimal interference from government. Simultaneously, the apex court not only upheld the right of minorities to “establish and administer educational institutions of their choice”, but also expanded this right to all citizens (including non-minorities).

EW comment. In a cover feature titled ‘Supreme Court’s freedom charter for Indian education’ (February 2003), EW hailed this historic judgement curtailing government interference and micro-management of private unaided education institutions. “It heralds a new era for Indian education and a rollback of the licence-permit-quota raj which has migrated from industry into the vitally important education sector,” commented your editors.

Saffronisation of school textbooks. In October, more than two years after the Delhi-based National Council for Educational Research & Training (NCERT) — an autonomous subsidiary of the Union HRD (education) ministry — drew up a new National Curriculum Framework for School Education (2000), it presented the nation with a new set of model social science textbooks for classes VI-IX.

Saffronisation of school textbooks. In October, more than two years after the Delhi-based National Council for Educational Research & Training (NCERT) — an autonomous subsidiary of the Union HRD (education) ministry — drew up a new National Curriculum Framework for School Education (2000), it presented the nation with a new set of model social science textbooks for classes VI-IX.

These textbooks generated a storm of protest from opposition parties, historians and academics who charged that they contained hindutva propaganda of the ruling BJP and its affiliates such as the RSS, Vishwa Hindu Parishad and the Bajrang Dal. Several well-established historical facts were omitted, reinvented and/or ‘saffronised’ in the new texts to align with the ideological predilections of the BJP.

EW comment. In a detailed story titled ‘Creeping saffronisation of Indian history’ (March 2003), your editors warned government and NCERT — the country’s largest school textbooks publisher — about the dangers of “undermining the nation’s plural cultural tradition, and planting the seeds of intolerance and discord in the minds of hundreds of thousands of impressionable young students in classrooms of the country”.

2003

Academic freedom with fetters. On August 14, in Islamic Academy vs Union of India, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court “clarified” the TMA Pai judgement and whittled down the right conferred upon unaided college managements to determine admissions and fix tuition fees. The apex court decreed the establishment of state-level committees chaired by retired high court judges to determine if admissions to private unaided professional education were made on merit, and if tuition fees they levied were reasonable.

EW comment. This dilution of the TMA Pai judgement was criticised in a cover story titled ‘Freedom with fetters: Supreme Court’s new fiat on professional education’ (EW September 2003). “The court has increased bureaucratic discretion and consequent corruption by allowing state governments to fix the management quota of each private college,” wrote your editors.

2004

Assault on IIMs/ IITS. On February 5, Union HRD minister Dr. Murli Manohar Joshi issued a terse five-paragraph order directing all six Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) to slash tuition-cum-residence fees payable by students admitted in the new academic year (2004-05) by 80 percent from Rs.1.3-1.75 lakh to a uniform Rs.30,000 per year. Earlier, Joshi had targeted the country’s seven Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) ordering them to route all alumni donations through a government constituted Bharatiya Shiksha Khosh trust.

Assault on IIMs/ IITS. On February 5, Union HRD minister Dr. Murli Manohar Joshi issued a terse five-paragraph order directing all six Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) to slash tuition-cum-residence fees payable by students admitted in the new academic year (2004-05) by 80 percent from Rs.1.3-1.75 lakh to a uniform Rs.30,000 per year. Earlier, Joshi had targeted the country’s seven Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) ordering them to route all alumni donations through a government constituted Bharatiya Shiksha Khosh trust.

EW comment. Our cover story ‘OUTRAGE! Joshi’s IIM-grab angers middle class India’ (EW March) joined the storm of protest from industry, academia and students against this diktat. “The minister’s tinkering with the proven structures and processes of the IITs and IIMs which have acquired global reputations for the high quality of problem-solving engineers and managers they produce, has proved particularly galling for the nation’s upwardly mobile urban middle class which highly values quality education, and has provoked a declaration of war… The ministerial order is clearly a case of arbitrary and irrational exercise of power,” wrote your editors while recommending the IITs/ IIMs to “reduce their dependence on government and evolve into self-governing independent institutions”.

General Election. In the 13th General Election called by the NDA government in April-May 2004, the BJP-led NDA suffered a shock defeat with the imperious Union HRD minister Dr. Murli Manohar Joshi failing in his bid for re-election from the university town of Allahabad.

Congress-led UPA government. Following the unexpected electoral rout of the BJP, a Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government was sworn in on May 22 in Delhi. In its Common Minimum Programme announced on May 28, the UPA pledged to increase spending on public education to 6 percent of GDP, impose a cess on all Central taxes to “universalise access to quality basic education”, and reverse the creeping communalisation of school syllabuses and texts.

EW comment. EW welcomed the intent of the new UPA government to increase national spending on education and “de-saffronise” school textbooks, advising it “to tread carefully”.

2005

National Curriculum Framework. The Congress-led UPA government released the National Curriculum Framework (NCF) for School Education 2005. The outcome of a mountain of labour spread over ten months of 21 national focus groups chaired by well-known scientist Prof. Yash Pal, NCF 2005 recommended a revised curriculum for schools to discourage rote learning; make curriculums holistic rather than textbook-centric and reduce the stress of terminal examinations.

EW comment. In a lead feature (July), while lauding NCF 2005 for being brilliantly written and “connecting knowledge to life outside the school; ensuring that learning is shifted away from rote methods; enriching the curriculum to provide for overall development of children rather than remain textbook-centric, and making examinations more flexible and integrated with classroom life”, we criticised it for fudging the vital question of the resource mobilisation effort required to implement its recommendations.

Quota cloud over private schools. Earlier in June in a draft Right to Education Bill, 2005, a special committee chaired by legal luminary Kapil Sibal recommended that 25 percent of capacity in elementary education (class I-VIII) in private schools should be reserved for poor children in their neighbourhoods.

Quota cloud over private schools. Earlier in June in a draft Right to Education Bill, 2005, a special committee chaired by legal luminary Kapil Sibal recommended that 25 percent of capacity in elementary education (class I-VIII) in private schools should be reserved for poor children in their neighbourhoods.

EW comment. In our cover story ‘Quota cloud over private schools’ (September 2005), we warned this government quota would become the thin end of a wedge for incremental government interference in the administration and operations of India’s private schools and encourage “backdoor nationalisation and/or intensifying inspector raj”. Earlier in January 2005, in a cover story titled ‘Rising criticism of Right to Education Bill 2005’, your editors cautioned: “the new Bill relies heavily upon the education bureaucracy which has conspicuously failed to improve quality of learning in government schools and has imposed asphyxiating stranglehold on private schools”.

Apex court clarification judgement. On August 13, 2005 delivering its verdict in P.A. Inamdar v. State of Maharashtra (2005), the apex court upheld its earlier verdict in TMA Pai v State of Karnataka (2002) and also “clarified” its judgement in the Islamic Academy Case (2003) which had diluted the apex court’s judgement in TMA Pai’s Case. Moreover it overruled its earlier judgement in Unnikrishnan’s Case (1993) in which it had held that private unaided colleges were obliged to provide professional (medicine, engineering) education to state government mandated quotas of students who topped their CETs (common entrance tests), at government prescribed tuition fees. Reaffirming its verdict in the TMA Pai Case, the court reiterated that Central and state governments have no right to appropriate admission quotas at arbitrary tuition fees in private professional colleges they haven’t funded or financed.

EW comment. The Supreme Court’s judgement and especially its abolition of state government quotas at prescribed fees outraged state governments and political parties nationwide. In a cover story titled ‘Professional education freedom verdict sparks constitutional crisis’ (October 2025), your editors welcomed the apex court’s judgement stating that rather than increasing capacity in government professional colleges, “profligate Central and state governments had resorted to the easy option of expropriating incremental capacity in private sector institutions at arbitrarily imposed, populist tuition fees to favoured constituencies,” thus wrecking private college finances.

2006

93rd Constitution Amendment 2006. To nullify the judgement of the Supreme Court in PA Inamdar vs. State of Maharashtra which reaffirmed that the State cannot impose its quota reservation policies on private unaided colleges, the Union HRD ministry responded with the 104th Constitution Amendment Bill which pointedly overruled this unanimous apex court judgement. Parliament unanimously approved the Bill which became the Constitution 93rd Amendment Act, 2005 when President Kalam signed it on January 20, 2006. Subsequently, a new clause was added to Article 15 of the Constitution permitting the State to decree reservations for any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes in all private educational institutions, including schools.

EW comment. In a cover story titled ‘Licence permit-quota-raj blitzkrieg dismays Indian academia’ (EW February), your editors criticised the UPA government for “recklessly pushing ill-considered legislation though a distracted Parliament” and “reservations policy which threatens to dumb down India’s few education institutions which can justifiably claim to be internationally benchmarked”, and discouraging private investment in higher education.

First ASER Report. The inaugural Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2005 — the country’s first independent nationwide survey of rural primary education — was released in January 2006. Published by the education NGO Pratham, ASER 2005 revealed that almost 60 percent (i.e 105 million) children in the age group seven-14 cannot read and comprehend a simple story of class II level difficulty, and 35 percent (62 million) cannot read a simple paragraph of class I level difficulty. The survey (confined to government and private schools in rural India) also revealed that 41 percent (72 million) children in the age group seven-14 are unable to solve two-digit subtraction or three number division sums.

EW comment. “ASER 2005 is a damning indictment of the abysmal quality education being delivered in the country’s 700,000 rural government and private primary schools… Six years after publication of PROBE 1999 stirred the conscience of the public and rudely awoke the nation’s educationists from their stupor, ASER 2005 indicates that teaching-learning achievements within the vitally important elementary education system continue to be abysmal. Against this backdrop, the emphasis of SSA and the massive universalisation of elementary education effort in general being made by the Central and state governments needs to be shifted from inputs to outcomes,” wrote your editors in a cover story ‘Taxes down the drain: Little learning in government schools’ (EW March 2006). Since then, the annual ASER survey and its findings have been regularly cited in EW stories, calling the government to focus attention on improving student learning outcomes.

EW comment. “ASER 2005 is a damning indictment of the abysmal quality education being delivered in the country’s 700,000 rural government and private primary schools… Six years after publication of PROBE 1999 stirred the conscience of the public and rudely awoke the nation’s educationists from their stupor, ASER 2005 indicates that teaching-learning achievements within the vitally important elementary education system continue to be abysmal. Against this backdrop, the emphasis of SSA and the massive universalisation of elementary education effort in general being made by the Central and state governments needs to be shifted from inputs to outcomes,” wrote your editors in a cover story ‘Taxes down the drain: Little learning in government schools’ (EW March 2006). Since then, the annual ASER survey and its findings have been regularly cited in EW stories, calling the government to focus attention on improving student learning outcomes.

OBC reservation diktat. On April 5, Union HRD minister Arjun Singh announced that the 17-party coalition UPA government at the Centre has approved his ministry’s proposal to reserve an additional 27 percent (in addition to the 22.5 percent reserved quota for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes) of capacity in Central government promoted universities and education institutions (JNU, IITs, IIMS, AIIMS, etc) for OBC (other backward castes) students. While this out-of-the-blue reservation diktat evoked studied criticism from the intelligentsia and media, the student community particularly in north India, responded with nationwide protests and campus rioting.

EW comment. Our cover story ‘Reservation shadow over campus India’ (EW May 2006) highlighted that this new reservation diktat would intensify competition for admission into the nation’s too-few high-quality institutions for ‘merit’ students. “The prime objective of the HRD ministry should be to address the supply side of higher education while simultaneously upgrading academic and research activities in India’s 380 universities, 15,800 colleges and other institutions to global standards. Legislating additional caste quotas will surely dilute academic standards and generate social tensions in campus India and society,” wrote your editors. Following a huge public furore and media (including EW) criticism, a special government committee recommended expansion of institutional capacity of Central government institutions to avoid reduction of the merit students’ quota.

2007

Foreign Educational Institutions Bill. Responding to persistent calls from a minority of academics and media (including EW), in March the Union HRD ministry released a Draft Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulation of Entry, Operation, Maintenance of Quality and Prevention of Commercialisation) Bill 2007, for public comment. The Bill while allowing foreign universities to set up physical campuses in India also set out a plethora of preconditions and regulations for them to fulfill. However, the tabling of the Bill in Parliament was scuttled at the last minute by the communist parties which formed part of the ruling UPA I coalition government.

EW comment. In a cover feature titled ‘Time to welcome foreign universities’ (October) your editors welcomed the Draft FEI Bill. “With only 9 percent of India’s youth in the 18-24 age group being able to access institutions of higher education against 15 percent in China, 50 percent plus in Europe and 80 percent in the US, and widespread protest in India Inc. about the employability of the great majority of India’s 2.5-3 million graduates per year, quite clearly the country’s tertiary education sector needs a radical makeover. And the best option available to attain both these objectives expeditiously is to roll out the red carpet for the brightest and best foreign education providers ready and willing to offer their superior campuses, contemporary curriculums and smart pedagogies to India’s eager-to-learn student community. But for this win-win outcome, some heavy ideological baggage in government as well as Indian academia has to be jettisoned,” wrote your editors.

NB. Continuous advocacy by progressive academics and media (including EducationWorld), resulted in the BJP/NDA government, voted to power at the Centre in 2014, to permit top-ranked, bona fide foreign universities to establish brick-n-mortar campuses in India in 2023.

NB. Continuous advocacy by progressive academics and media (including EducationWorld), resulted in the BJP/NDA government, voted to power at the Centre in 2014, to permit top-ranked, bona fide foreign universities to establish brick-n-mortar campuses in India in 2023.

EW India School Rankings. The inaugural EducationWorld India’s School Rankings field-based survey rating and ranking 83 schools was published. Since then, this annual survey conducted by professional market research agencies has evolved into the annual EW India School Rankings (EWISR) — the world’s largest and most comprehensive school rankings survey — rating and ranking over 4,000 schools in 458 cities and towns countrywide across 14 parameters of K-12 education excellence.

EW comment. “The objective of EWISR is to aid and enable parents to select the most aptitudinally suitable school for their children. Simultaneously, a parallel objective is to stimulate and motivate institutional managements to strive for delivering balanced, holistic education and benchmark themselves with globally admired schools,” wrote your editors (EW August 2007). Since then, the annual EWISR has transformed primary-secondary education, impacting the importance of holistic (cf. academic) education upon the entire K-12 sector and promoting healthy competition among schools to be top-ranked in their categories.

2008

EW blueprint for supplementary education budget. Union Budget 2008-09 was presented by Union finance minister P. Chidambaram. In his 90-minute budget speech, the finance minister acknowledged that “education and health are the twin pillars on which rests the edifice of social sector reforms” and announced that the Central government’s expenditure in the education sector will be 20 percent higher at Rs.34,400 crore in fiscal 2008-09, of which Rs.13,100 crore is for the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (elementary education for all) programme; Rs.8,000 crore for the mid-day meal scheme (to cover a massive 139 million children) and Rs.4,554 crore for upgrading secondary education.

EW blueprint for supplementary education budget. Union Budget 2008-09 was presented by Union finance minister P. Chidambaram. In his 90-minute budget speech, the finance minister acknowledged that “education and health are the twin pillars on which rests the edifice of social sector reforms” and announced that the Central government’s expenditure in the education sector will be 20 percent higher at Rs.34,400 crore in fiscal 2008-09, of which Rs.13,100 crore is for the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (elementary education for all) programme; Rs.8,000 crore for the mid-day meal scheme (to cover a massive 139 million children) and Rs.4,554 crore for upgrading secondary education.

EW comment. With the Union Budget 2008-09 making a paltry allocation for education, in our path-breaking story ‘Blueprint for a Supplementary Budget for Primary Education’, your editors presented an innovative supplementary resource mobilisation schema for public education to equip government schools suffering infrastructure deficiencies such as laboratories, libraries and lavatories. With Dr. AS Seetharamu, former professor of education at ISEC, Bangalore, estimating the expenditure of equipping all government schools countrywide with libraries, laboratories and lavatories (lib-lab-lav) at Rs.47,725 crore, the EW schema provided a roadmap/calculus to mobilise the said sum by way of reducing establishment expenses; modestly reducing unwarranted middle-class subsidies; gradual disinvestment of public sector enterprises; a modest Rs.1,000 flat tax for all income tax payers and cess on corporates, among other proposals. Since then coterminously with presentation of the Union Budget every year, your editors have been presenting updated resource mobilisation schemas to massively fund public education. Alas, despite inviting debate and critiques of these schemas, there has been no response from government or eminent economists.

2009

Parliament passes RTE Act. On August 14, the Lok Sabha unanimously passed the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Bill, 2009 (aka RTE Act), which made it incumbent upon the State to provide free and compulsory education to all children aged between six to 14 years. The Bill was earlier passed by the Rajya Sabha on July 20.

Parliament passes RTE Act. On August 14, the Lok Sabha unanimously passed the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Bill, 2009 (aka RTE Act), which made it incumbent upon the State to provide free and compulsory education to all children aged between six to 14 years. The Bill was earlier passed by the Rajya Sabha on July 20.

EW comment. While EW welcomed unanimous legislation of the RTE Act, 2009 by Parliament, in an early response editorial the very next month (September), we warned that s.12 (i) (c) of the RTE Act, 2009 which mandates all private unaided schools to reserve 25 percent of capacity in class I for children from poor households in their neighbourhood and retain them until class VIII will “encourage creeping nationalisation of these institutions”. “While it’s true that elite private schools will benefit by way of greater student diversity, it’s unjust and probably unconstitutional for government to visit the consequences of its failure to improve standards in its own schools, upon privately-promoted institutions,” wrote your editors.

Subsequently in a detailed cover story ‘RTE shadow over India’s most admired schools’ (EW October 2010), we reiterated that “the misgivings of private school managements and other stakeholders (parents, teachers) have transformed into snowballing fear of creeping erosion of academic and administrative autonomy.”

NB. Since it was enacted in 2009, the high promise RTE Act has permitted blatant discrimination against private schools. For instance s.19 prescribes a wide range of mandatory infrastructure provisions for private schools but exempts 1.20 million government schools from adhering to them. Moreover, the impact of s.12 (1)(c) has been diluted by a Supreme Court judgement (2012) which exempted minority (and boarding) schools. Since then, the provision has been substantially rendered ineffective with a large number of schools claiming linguistic and religious minority status.

2010

First ranking of India’s most admired preschools. The inaugural EW India Preschool Rankings (EWIPR) survey (conducted by an independent market research agency which interviewed 1,522 sample respondents in six major cites across the country) was published. The respondents rated the country’s most prominent pre-primaries under ten parameters of early education excellence rating and ranking Top 20 pre-primaries in six major cities. Aware of popular ignorance about the critical importance of professionally administered ECCE (early childhood care and education), this was followed by the first EW Early Childhood Education Global Conference staged in India. Since then, the annual EWIPR has evolved into the country’s largest preschools rankings survey with league tables ranking over 500 preschools in 17 cities countrywide under ten parameters of early childhood education excellence.

First ranking of India’s most admired preschools. The inaugural EW India Preschool Rankings (EWIPR) survey (conducted by an independent market research agency which interviewed 1,522 sample respondents in six major cites across the country) was published. The respondents rated the country’s most prominent pre-primaries under ten parameters of early education excellence rating and ranking Top 20 pre-primaries in six major cities. Aware of popular ignorance about the critical importance of professionally administered ECCE (early childhood care and education), this was followed by the first EW Early Childhood Education Global Conference staged in India. Since then, the annual EWIPR has evolved into the country’s largest preschools rankings survey with league tables ranking over 500 preschools in 17 cities countrywide under ten parameters of early childhood education excellence.

EW comment. The annual EW India Preschool Rankings and EW Early Childhood Education Conferences together have impacted the critical importance of early childhood care and education upon the national consciousness. “Hopefully this pioneer preschools survey will stimulate the multiplication and upgradation of nascent ECE institutions countrywide. Indeed, the rapid multiplication and improvement of preschools across the country is an essential pre-condition of endowing the vast majority of India’s neglected and short-changed children with a sound foundation for life-long learning,” wrote your editors in a cover story (EW May 2010).

NB. Your editors’ persistent advocacy of professionally administered ECCE has paid off. National Education Policy 2020 mandates three years of compulsory ECCE for all children in the 3-6 age bracket countrywide. To this end, the centuries-old 10+2 school system has been replaced by a new 5+3+3+4 school continuum for all children.

2011

Mandatory Teacher Eligibility Test. On February 11, the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE) issued guidelines to all state governments and Union territories for conducting the Teacher Eligibility Test (TET). In accordance with s.23 (1) of the RTE Act, NCTE made clearance of TET mandatory for all new teachers recruited by the Central and state governments with effect from the academic year 2011-12.

EW comment. EW endorsed the introduction of TET to ensure teachers meet minimum teaching quality standards. However subsequently with reports of large-scale cheating, marks-for-money and other teacher appointment scams being reported from several states (West Bengal, Maharashtra, etc), EW news reports made a strong case for overhauling of TET exams.

EW comment. EW endorsed the introduction of TET to ensure teachers meet minimum teaching quality standards. However subsequently with reports of large-scale cheating, marks-for-money and other teacher appointment scams being reported from several states (West Bengal, Maharashtra, etc), EW news reports made a strong case for overhauling of TET exams.

Cabinet clears NCHER Bill. On December 21, the Union cabinet cleared the National Commission of Higher Education and Research (NCHER) Bill 2011, which envisages an overarching body in higher education to supervise universities and technical institutes. NCHER will subsume all existing regulatory bodies, including UGC, AICTE and Council of Distance Education, and will comprise 70 members, with representatives from every state and regulatory bodies. The proposal to establish NCHER was recommended by the Yash Pal Committee and the National Knowledge Commission.

EW comment. In our special report ‘Need for genuinely inclusive debate’ (EW February 2012), while welcoming the NCHER Bill, as a “brave reformist initiative”, your editors criticised its drafting committee for not consulting “any private university or higher education institution”. “This historic initiative which proposes a new architecture for the country’s higher education system should be the outcome of a genuinely consultative process involving all stakeholders — state governments, private universities, academics and students — to ensure its smooth passage through Parliament and effective subsequent implementation,” wrote your editors.

NB: In September 2014, the new BJP-led NDA government withdrew the NCHER Bill, 2011.

2012

Supreme Court upholds RTE Act. On April 12, 2012 in a landmark verdict in Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan vs. Union of India & Anr (Writ Petition (C) No. 95 of 2010), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the Union government’s Right to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, and particularly the controversial s.12 (1)(c) (reservation of 25 percent capacity of poor neighbourhood children in elementary classes of private schools). But the full impact of reservation was diluted by exempting minority (and boarding) schools.

Supreme Court upholds RTE Act. On April 12, 2012 in a landmark verdict in Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan vs. Union of India & Anr (Writ Petition (C) No. 95 of 2010), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the Union government’s Right to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, and particularly the controversial s.12 (1)(c) (reservation of 25 percent capacity of poor neighbourhood children in elementary classes of private schools). But the full impact of reservation was diluted by exempting minority (and boarding) schools.

EW comment. Arguing that the judgement will force open the flood gates of private schools for entry of dreaded licence-permit-quota-raj, your editors in a detailed cover story ‘Supreme Court green light for licence-permit-quota-raj in school education’ (EW May 2012) wrote: “Quite patently, the majority judgement which is prefaced by the remark “to say that a thing is constitutional is not to say it is desirable” is based on a technical and strained interpretation of constitutional law, and indicates minimal awareness of the grassroots reality of the government school system which is in a state of rigour mortis because of numerous sins of omission and commission of the education bureaucracy at the Centre and in the states.

Regrettably, it has recklessly given a green light to these very educrats to introduce their discredited licence-permit-quota and inspector regime into private K-12 education. They will surely torpedo the country’s budget schools and spread the contagion of corruption within the country’s hitherto insulated private unaided non-minority schools.”

2013

India’s most admired engineering colleges. In June 2013, the inaugural EW ranking of (non-IIT and NIIT) engineering colleges and private B-schools was published. Since then, this survey has evolved into the annual EW India Higher Education Rankings which rates and ranks the country’s Top 300 private and government universities, Top 500 private/government autonomous and non-autonomous colleges, and Top 100 private engineering colleges and B-schools across 15 parameters of higher education excellence. IITs and NITs were omitted from the rankings as these highly subsidised Central government-funded engineering colleges routinely top all media rankings of engineering and technology institutions.

EW comment. “The EW survey will serve the useful purpose of aiding and abetting higher secondary school-leavers to choose institutes most suitable to their aptitudes and preferences,” wrote your editors in the cover story (EW June 2013).

National ECCE Policy. On September 20, the Union cabinet approved a draft National Early Childhood Care and Education (NECCE) policy of the Union ministry of women and child development (WCD). Stating that the “cardinal principles” on which the policy draft is based are “universal access, equity and quality in ECCE”, the policy recommended transformation of all 1.35 million Central government anganwadi centres (AWCs) — maternal and child nutrition centres — into AWCs-cum-creches “with adequate infrastructure and resources for ensuring a continuum of ECCE in a life-cycle approach and child-related outcomes”, a long-standing demand of EducationWorld. The policy also set minimum infrastructure, teacher qualifications and teacher-pupil ratio requirements for all private preschools.

EW comment. In our very next issue (EW October), in a news report welcoming “the provision for transforming the country’s 1.35 million anganwadis into full-fledged nurseries/preschools as long overdue”, your editors warned that “almost all noble and high-sounding education legislation has been perverted in implementation. In the circumstances, the admittedly necessary regulation of preschool education may prove to be a two-edged sword.”

NB. This warning/ prophecy proved correct. India’s AWCs have not been adequately upgraded to transform into full-fledged nurseries/ preschools and remain inadequately staffed mother and child nutrition centres to this day.

2014

SC medium of instruction verdict. In a landmark judgement delivered on May 6, 2014 in State of Karnataka & Anr. vs. Associated Managements of (Government Recognised Unaided English Medium) Primary & Secondary Schools & Ors, the Supreme Court upheld a 2008 Karnataka high court judgement which had quashed a state government order issued in 1994 mandating Kannada or mother tongue as the compulsory medium of instruction in all primary schools (classes I-V) statewide. The apex court ruled that imposing any language as the medium of instruction violates the fundamental right of parents and children to choose their preferred language of instruction in school.

EW comment. EW applauded the SC verdict in a detailed news report (EW June 2014): “Decades of confusion, obfuscation, harassment and corruption aided and abetted by successive governments in the southern state of Karnataka (pop. 57 million) on the issue of Kannada or mother tongue being employed as the mandatory language of instruction in all 60,000 primary schools (classes I-V) including private schools in the state, has been finally ended by the Supreme Court… and it’s curtains down for the state’s language chauvinists and vernacular language textbook publishers.”

Delhi University FYUP rollback. On June 27, Delhi University issued a directive to affiliated colleges to cancel its four-year undergraduate programme (FYUP). It directed affiliated colleges to admit students in the 2014-15 academic year “under the scheme of courses that were in the academic session 2012-13”. With the BJP, which won a landslide victory in General Election 2014, having promised in its manifesto to scrap FYUP, the Central government-funded University Grants Commission (UGC), the country’s apex higher education regulatory body which had approved FYUP in 2013, made a supine volte face directing DU to revert to the traditional three-year programme.

EW comment. In a Special Report titled ‘Delhi University’s FYUP disaster’ (EW July 2014), your editors lamented the rollback of FYUP. “Undeniably DU’s FYUP even if hastily and imperfectly designed as alleged, is a conceptually innovative undergrad programme which could have benefited India’s moribund and rapidly obsolescing higher education system which has failed to keep pace with the rest of the world…With India’s premier university opting for safe mediocrity over a great leap forward, the voyage of its graduates will continue to be bound in shallows and misery,” wrote your editors.

NB. The FYUP was reintroduced in 2022 by DU after promulgation of the National Education Policy 2020 which directs universities/colleges countrywide to introduce FYUP undergrad degrees.

2015

IIM Bill backlash. In June, the Union HRD ministry uploaded a new Indian Institutes of Management (IIM) Bill 2015 on its website for public comment and discussion. Although the stated objects of the Bill were to designate the IIMs as “institutions of national importance” and to invest them with degree awarding powers (under separate IIM Acts currently, they are restricted to awarding postgraduate diplomas and fellowships), several provisions of the Bill substantially expanded the supervisory and regulatory powers of the Central government, i.e, the Union HRD ministry. Appointments to the board of governors, academic council, director, faculty and even syllabus and curriculum formulation were subject to government approval. Moreover as per the draft Bill, the ministry’s approval will be required for matters related to admission criteria, scholarships and fellowships.

EW comment. EW strongly criticised the IIM Bill 2015 – the handiwork of HRD minister Smriti Irani. “Suddenly, there’s pervasive fear, not only within the academic councils and faculty but within all stakeholders — alumni, industry and students — that the national and global reputation of these B-schools painstakingly developed over six decades, could be quickly destroyed by a bull- in-a-china-shop BJP-led NDA government,” wrote your editors in a cover story titled ‘Hostile takeover bid 2.0’ (EW August). In subsequent issues, we continued to highlight the dangers of curtailing the autonomy of IIMs, resulting in the Bill being recast and HRD minister Irani being transferred to the textiles ministry a year later (2016).

EW comment. EW strongly criticised the IIM Bill 2015 – the handiwork of HRD minister Smriti Irani. “Suddenly, there’s pervasive fear, not only within the academic councils and faculty but within all stakeholders — alumni, industry and students — that the national and global reputation of these B-schools painstakingly developed over six decades, could be quickly destroyed by a bull- in-a-china-shop BJP-led NDA government,” wrote your editors in a cover story titled ‘Hostile takeover bid 2.0’ (EW August). In subsequent issues, we continued to highlight the dangers of curtailing the autonomy of IIMs, resulting in the Bill being recast and HRD minister Irani being transferred to the textiles ministry a year later (2016).

Skill India initiative launched. On the first ever World Youth Skills Day (July 15), the BJP-led NDA government launched the Skill India initiative. A National Skill Development Mission and a new National Policy for Skill Development & Entrepreneurship (NPSDE) 2015 are the main highlights of the initiative. The national mission is a booster to achieve NPSDE in mission mode.

EW comment. In an Education News report (EW August) EW welcomed the launch of Skill India mission as a “comprehensive, ambitious and overdue” initiative, but commented: “the moot point is whether the under-developed Indian economy has the capacity and resources to implement it”.

NB. Since then your editors have continuously highlighted the neglect of vocational education and slow progress of Skill India mission (only 2 percent of India’s 560 million workforce has received formal skills training as per The Economic Survey 2023-24) and advocated “a clear roadmap on how to meet the skilling challenge”. “To adequately skill the world’s largest youth population, the BJP/NDA 3.0 and succeeding governments have no option but to ideate resource mobilisation and deployment strategies to more than double the national expenditure for public education from the current 2.7 percent of GDP to 7 percent,” wrote your editors in the cover story titled ‘Skilling reskilling upskilling fever raging countrywide’ (EW August 2024).

2016

National Institutional Ranking Framework. On April 4, the first official (Union HRD ministry) league tables ranking the Top 100 Indian universities, engineering colleges and B-schools were released in New Delhi. Based on a National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) devised by a 16-member “core committee” of academics selected by the HRD ministry, the first-ever government league tables evaluated category ‘A’ higher education institutions under six parameters, viz, teaching, learning and resources; research and professional practice; graduation outcomes; outreach and inclusivity. Since then, NIRF has evolved into India’s largest government higher education institutions (HEIs) rating and ranking exercise.

However unlike the EducationWorld India Higher Education Rankings (EWIHER) introduced in 2013, NIRF only ranks ‘participating” HEIs that submit prescribed data to the Union education ministry.

EW comment. Responding by way of a news report filed from Delhi (EW May 2016), we commented that the NIRF rankings — based entirely on self-submitted data — “are less than credible”. Subsequently in several critiques of the annual NIRF, your editors have highlighted voluntary participation and self-submitted data design features of NIRF. “HEIs that participate in NIRF are obliged to submit dozens of data sets in prescribed formats for evaluation of the quality of their teaching, learning and research capabilities. The identity of assessors is not known and although participating institutions are warned that the information submitted by them is subject to cross-checking and audit, the assessment process permits a high degree of subjectivity. Moreover, there’s a widespread belief that NIRF is heavily biased in favour of government HEIs,” wrote your editors.

National Education Policy — Subramaniam Committee Report. The report of a five-member committee chaired by former Union cabinet secretary T.S.R. Subramanian, constituted in October 2015 by the Union HRD ministry to draft a New Education Policy (NEP) 2016, was presented to HRD minister Smriti Irani on May 28. The report provoked a storm when Irani refused to heed Subramanian’s demand to make the report available to the public for debate and discussion. Unfazed, Subramanian called a press conference in Delhi on June 23 and suo motu released the 217-page report of the committee, which has made 90 recommendations for incorporation into NEP 2016. Three months later, her successor HRD minister Prakash Javadekar dismissed the report as “only one of the inputs” for framing a new NEP.

National Education Policy — Subramaniam Committee Report. The report of a five-member committee chaired by former Union cabinet secretary T.S.R. Subramanian, constituted in October 2015 by the Union HRD ministry to draft a New Education Policy (NEP) 2016, was presented to HRD minister Smriti Irani on May 28. The report provoked a storm when Irani refused to heed Subramanian’s demand to make the report available to the public for debate and discussion. Unfazed, Subramanian called a press conference in Delhi on June 23 and suo motu released the 217-page report of the committee, which has made 90 recommendations for incorporation into NEP 2016. Three months later, her successor HRD minister Prakash Javadekar dismissed the report as “only one of the inputs” for framing a new NEP.

EW comment. In a cover story titled ‘Subramanian Committee Report: Love’s labour lost’ (EW November), your editors endorsed the comprehensive reforms-oriented report. “The detailed 217-page report diagnoses the myriad ills of the country’s education system (KG-Ph D) which has suffered continuous under-funding and neglect, and the reality that contemporary India grudgingly hosts the world’s largest child population (480 million). It proposes comprehensive reform… but the well-reasoned, constructive and indeed erudite recommendations of the Subramanian Committee have little chance of being incorporated into the New Education Policy 2016,” wrote your editors.

NB. The Subramanian Committee Report was shelved, and another NEP Drafting Committee was constituted under the chairmanship of former ISRO chairman Dr. K. Kasturirangan in June 2017

Mission Million Memorial Libraries Project Launch. On November 7, the first children’s library under the EducationWorld Foundation’s ‘Million Memorial Libraries Now’ project was inaugurated at the Parikrma Centre for Learning, Sahakarnagar, Bangalore, a free-of-charge K-12 school established for underprivileged children from slum households. The first library under this project was established following a donation of Rs.5 lakh contributed by your editors and Anil, Shyama and Bharati Thakore in memory of the late Malati & Vinoo Thakore. The expectation was that this memorial library would serve as a model for India’s large middle class (150 million households) to establish libraries in their neighbourhood and ancestral towns/villages in memory of parents and loved ones.

EW comment. Unfortunately, despite the Malati & Vinoo Thakore Memorial Library offering a model to establish libraries for underprivileged children in under-resourced schools, the ‘Million Memorial Libraries Now’ project has proved a dismal failure — evidence of gratitude and idealism deficit in middle class India.

2017

National Testing Agency constituted. In November 2017, the Union Cabinet cleared establishment of a National Testing Agency (NTA) to conduct all pan-India higher education admission entrance tests. Initially NTA will conduct all entrance exams currently being conducted by CBSE. Conduct of other higher education entrance examinations will be assumed by NTA progressively.

EW comment. EW welcomed the establishment of NTA as its creation “will free CBSE, AICTE, IITs, IIMs and other agencies from examination and assessment duties thus allowing them to focus on their core mandate of education and research provision”.

NB. Subsequently NTA suffered embarrassing glitches while conducting national examinations written by thousands of students clamouring for admission into the country’s much-too-few acceptable quality higher education institutions. In a cover story titled ‘Rectifying NTA exams disaster’ (EW July 2024), your editors recommended complete overhaul of NTA.

2018

Higher Education Commission of India Bill. On June 28, the Union Cabinet approved a draft Higher Education Commission of India (Repeal of UGC Act) Bill, 2018, and posted it on the website of the Union HRD ministry for public comment. The Bill proposed replacement of the University Grants Commission (UGC, estb.1956), the country’s apex higher education regulatory authority with a Higher Education Commission of India (HECI), to improve the quality of academic instruction and maintenance of academic standards.

EW comment. While EW welcomed disbandment of the Soviet-style over-arching command and control UGC, your editors reported strong opposition from higher ed academics and highlighted that the commission is likely to be dominated by Central government bureaucrats and appointees. Moreover, the Bill is silent on the issue of grants sanctioned and disbursed to the country’s higher education institutions (HEIs), an important function of UGC. “The Bill proposed that the Union HRD ministry will directly fund Central and state universities arousing fears of erosion of autonomy of HEIs,” wrote your editors, predicting that “it’s very unlikely that HECI will replace UGC in the near future” (Education News, EW August).

NB. The Higher Education Commission of India Bill is yet to be tabled in Parliament.

2019

Kasturirangan Committee’s Draft NEP. The Draft National Education Policy (NEP), authored by a nine-member committee of academics chaired by eminent space scientist K. Kasturirangan, former chairman of ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation), was released for public debate on May 30.

The 484-page KR Committee Report proposed an overhaul and restructuring of Indian education from pre-primary to Ph D. Among its major recommendations: integration of three years of foundational early childhood education into the school education continuum; shift from rote learning to inquiry-based and experiential pedagogies in primary-secondary education; integration of vocational education and training into school and higher education; establishment of State School Regulatory Authorities (SSRA) to monitor and regulate school education and a National Higher Education Regulatory Council (NHERC) for HEIs. In addition, the KR Committee recommended setting up several other committees — HECI, GEC, NAC, HEGC, NTF — all to be chaired by academics of “unimpeachable integrity” to supervise and regulate school and higher education.

EW comment. In a detailed 13-page cover story titled ‘More government more governance’ (July), EW critically analysed the KR Committee’s Draft NEP 2019. “Debated, deliberated and written over a period of two years, inevitably the KR Committee’s draft NΕΡ 2019 contains several valuable recommendations for the comprehensive reform of 21st century India’s obsolete education system across the board from pre-primary to Ph D… But unfortunately, the KR Committee composed as it is of establishment academics with statist, if not shop-worn leftist mindsets, has not been able to resist the temptation to recommend strict control and command of private education institutions which to all intents and purposes are doing very well, especially when compared to government owned/managed schools and HEIs. What Indian education needs is the Central and state governments to focus on nurturing the country’s government-run 1.6 million anganwadis, 1.20 million primary-secondaries, and public undergrad colleges and HEIs and lightly, if at all, regulate private education institutions,” wrote your editors.

EW comment. In a detailed 13-page cover story titled ‘More government more governance’ (July), EW critically analysed the KR Committee’s Draft NEP 2019. “Debated, deliberated and written over a period of two years, inevitably the KR Committee’s draft NΕΡ 2019 contains several valuable recommendations for the comprehensive reform of 21st century India’s obsolete education system across the board from pre-primary to Ph D… But unfortunately, the KR Committee composed as it is of establishment academics with statist, if not shop-worn leftist mindsets, has not been able to resist the temptation to recommend strict control and command of private education institutions which to all intents and purposes are doing very well, especially when compared to government owned/managed schools and HEIs. What Indian education needs is the Central and state governments to focus on nurturing the country’s government-run 1.6 million anganwadis, 1.20 million primary-secondaries, and public undergrad colleges and HEIs and lightly, if at all, regulate private education institutions,” wrote your editors.

2020

Covid-19 pandemic schools’ lockdown. On March 16, the Union government announced the closure of all schools, colleges and universities across the country to control and check the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. All major examinations, including public entrance exams such as JEE and NEET were postponed and several school-leaving board exams in the states of the Indian Union abandoned midway. This story was repeated in higher and professional education institutions, which also had to close down campuses and discontinue classes and project work mid-semester. Schools and HEIs were advised to move their classrooms to the online mode.

Covid-19 pandemic schools’ lockdown. On March 16, the Union government announced the closure of all schools, colleges and universities across the country to control and check the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. All major examinations, including public entrance exams such as JEE and NEET were postponed and several school-leaving board exams in the states of the Indian Union abandoned midway. This story was repeated in higher and professional education institutions, which also had to close down campuses and discontinue classes and project work mid-semester. Schools and HEIs were advised to move their classrooms to the online mode.

EW comment. Initially your editors welcomed the closure of schools as a cautionary measure to protect vulnerable children from the dreaded Coronavirus. However, with the schools’ lockdown countrywide transforming into the world’s second longest (after Uganda) education lockdown of 56 weeks and resulting in unprecedented learning loss, EW was at the forefront of the restart school campaign. In a cover story titled ‘Why schools should reopen now’ (EW July), your editors highlighted the unprecedented damage suffered by the world’s largest child and youth population by way of loss of learning and called for immediate reopening of schools. “The balance between children’s safety against the Covid-19 pandemic and their right to protect their future livelihoods needs to be restored. The national interest demands no more time is lost in restarting India’s long shuttered schools with adequate safety protocols,” wrote your editors.

NB: Schools reopened in late 2021 after 56 weeks of closure, and longer in some states.

National Education Policy 2020. The much-awaited National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, formulated after an interregnum of 34 years and incorporating most of the detailed recommendations of the K. Kasturirangan Committee, was presented to the public on July 29. The 65-page NEP 2020 mandates reconfiguration of the 10+2 school system with a new 5+3+3+4 school continuum to include three years of compulsory ECCE for all children countrywide in the 3-6 age bracket; curriculum, pedagogy and exam reforms in school education to encourage conceptual comprehension, creativity and critical thinking capabilities rather than rote learning; introduction of certified multiple exit and re-entry options and a system of credits to be stored in a national ABC (academic bank of credits) digital repository; phasing out the system of all undergrad colleges affiliating with parent universities, and graded autonomy for undergrad colleges under a ‘light but tight’ regulatory framework; establishment of a National Research Foundation and permitting top-ranked foreign universities to set up campuses in India.

EW comment. Our comprehensive cover story ‘NEP 2020: Visionary charter, educracy shadow’ (EW August 2020) carefully examined NEP 2020 and its recommendations for reforming Indian education from early childhood to higher education. It concluded that the policy is an amalgam of high rhetoric clouded by implementation uncertainty, because it has established too many regulatory supervisory agencies. “Formulated after an interregnum of 34 years and crafted over four years following recommendations of two high-powered committees, the new education policy aroused great expectations. But NEP 2020 is an amalgam of high rhetoric clouded by implementation uncertainty because of its conspicuous failure to make a clean break from bureaucratic control-and-command,” wrote your editors.

NB. Four years after NEP 2020 was approved, the supervisory and regulatory committees it mandates including GEC, NAC, HEGC have not been constituted. After writing the 484-page NEP draft, committees chaired by Dr. Kasturirangan have drafted NCF-FS (National Curriculum for Foundational Stage) and National Curriculum for School Education (NCF-SE). But with Dr. K’Rangan suffering bad health, all further work on writing curriculums for teacher and adult education seems to have slowed if not halted. The ground has been prepared for NCFSE, but the country’s 1.4 million Central government anganwadis have not received the funding and upgradation necessary to implement the NCF-FS in the government sector. While ECA (Early Childhood Association) and the country’s estimated 55,000 private pre-primaries have welcomed NCF-FS, government sector pre-primaries which require Centre-State government funding are in stasis.

Likewise, in K-12 education while 30,000 upscale private (and Central government) schools affiliated with the national CBSE and CISCE exam boards have begun implementing pedagogy and curriculum reforms mandated by NEP 2020, the vast majority of schools affiliated with 52 state examination boards are still stuck in the rote memorisation pedagogies rut. And in higher education, the process of conferment of autonomy to even premier, top-ranked government and aided undergrad colleges by their massive parent universities has not begun, even as autonomous new genre private varsities enthusiastically welcomed by your editors, are rapidly closing the gap with best offshore institutions of higher education.

As a result, the teaching-learning standards gap between government and private education institutions is widening instead of narrowing. In the final analysis, it’s the conspicuous failure of the Central and state governments to raise their annual outlays for public education that’s the root of the problem. Unless this nettle is grasped, the backwardness of public education will persist. For instance in the Union Budget 2024-25, the Centre’s allocation for education at Rs.1.48 lakh crore has declined as a percentage of GDP compared to 2023-24. Ditto in the states as government expenditure on populist freebies increases, allocations for education are being slashed.

2021

Landmark fees regulation judgement. Upholding two sets of appeals filed by the Indian School, Jodhpur and Association of Private Unaided Schools of Rajasthan against the state government of Rajasthan, on May 3, the Supreme Court read down, i.e modified, sections of the Rajasthan Schools (Fees Regulation) Act, 2016 (FRA). The appeals challenged an order of the state government — upheld by the high court — directing private schools to collect only 70 percent of tuition fees — and no other — from parents for the academic year 2020-21 since all schools had been under lockdown during the Covid pandemic and were teaching online. The state government contended that private schools had not provided co-curricular education and transport and other services to students, and therefore parents were not obliged to pay for them. In a detailed judgement the Supreme Court bench held that the right to determine the fees payable by students is vested in every school’s “management alone” by the apex court’s verdict in the T.M.A. Pai Case, and that the state government has no right to vary the terms of the contrac between schools and parents.

EW comment. In an Education News report in the very next issue (EW, June) your editors welcomed the apex court’s detailed and well-reasoned judgement as it “lays down important principles of law which are applicable countrywide. It unambiguously affirms the right of school managements to determine the total fees payable by parents and upholds the sanctity of contracts between parents and schools”.

Moreover with several state governments following Rajasthan’s example and succumbing to intensifying pressure from parents demanding reduction of private school fees because of income and job losses suffered during the Covid-19 pandemic, “this landmark judgement is a slap in the collective face of the Central and state governments whose officials believe that they have an unfettered right to interfere with contracts voluntarily negotiated between citizens,” wrote your editors.

2022

Common University Entrance Test. On March 21, University Grants Commission announced a Central University Entrance Test (CUET) for admission into undergraduate programmes of all 45 Central government universities (including Delhi University and affiliated colleges) from the start of the academic year 2022-23. The objective: to lessen financial and mental stress of school-leavers having to write multiple entrance tests of undergrad colleges, to free undergrad colleges and universities from the stress of conducting their own entrance tests and eliminate the phenomenon of popular colleges notifying sky-high cut-off scores in class XII board exams for admission into some study programmes.

EW comment. The following month (April), EW deplored the hasty promulgation of CUET without debate and warned that the introduction of a mandatory CUET for admission into much-prized undergrad colleges of Central universities poses the danger of diluting formal higher secondary schooling to the advantage of edtech and coaching/tutorial companies that drill and skill students to pass examinations rather than acquire in-depth knowledge of subjects. Moreover with the first phase of the exam held on July 15-20 in 554 cities countrywide marked by chaos and confusion, in a Special Report titled ‘Repairing CUET collateral damage’ (EW August 2022), your editors wrote: “even though CUET is a fait accompli, its rules, regulations and mandate have to be tweaked to repair the collateral damage that its peremptory introduction has caused”.

NCF for Foundational Stage 2022. The National Curriculum Framework for Foundational Stage (NCF-FS) 2022 for children in the three-eight age group was formally launched by Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan on October 20. The 360-page NCF-FS 2022 unambiguously prescribes learning through play — conversation, stories, toys, music, art and crafts — and prohibits textbooks for children below age six. This unambiguous pedagogy prescription for the foundational stage cleared widely prevalent confusion among ECCE providers, many of whom prematurely impose textbooks and exams on youngest children.

EW comment. NCF-FS 2022 was welcomed by EW “for the vastness of areas covered and great combination of curriculum assessment and teacher training” (Education News December 2022). However your editors pointed out that “the real challenge is for the Central and state governments to operationalise NCF-FS 2022 in government schools, particularly the country’s 1.4 million Central government anganwadi centres” because of poor funding to the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme which funds AWCs. “As in the case with numerous official initiatives in education, NCF-FS is likely to flounder on the rock of funding,” predicted your editors.

2023

NCF for School Education 2023. The National Curriculum Framework for School Education (NCF-SE) 2023 outlining ways and means to implement the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 in the country’s 1.5 million primary-secondary schools was presented to the nation on April 6. NCF-SE is an exhaustive and detailed document of 628 pages providing a road-map for seamless integration of 13 curricular goals for transforming school education in all its stages. The draft is supplemented by manuals written by 25 focus groups.

EW comment. In a detailed cover story (EW August), we summarised the NCF-SE 2023, its implementation challenges and way forward, for the benefit of teachers, parents and students. Commented your editors: “A common factor for the successful implementation of NCF-FS, NCFSE and the imminent National Curriculum for Teacher Education and National Curriculum for Adult Education is larger budgetary allocation. Therefore, government expenditure (Centre plus states) for public education must forthwith be raised to 6 percent of GDP.”

NB. The issue of increasing the annual outlay (Centre plus states) for education has not been squarely addressed for the past half century since the Kothari Commission first proposed 6 percent of GDP in 1967. Your editors’ repeated calls and presentation of painless roadmaps to attain this desideratum, have been sidestepped by establishment economists and academics with nostrums such as “inputs don’t guarantee outcomes” and “priority should be efficiency of expenditure”. For mysterious reasons, politicians and academics can’t grasp the truism that schools and colleges should be infrastructurally well-equipped and furbished institutions that children and youth love to attend and learn within.

Green light to foreign universities. In early November, the Delhi-based University Grants Commission (UGC) notified the UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations, 2023. The notification provides a legal and regulatory framework for foreign universities to establish owned campuses in India and sets terms and conditions for entry of FHEIs. Among them: Applicant foreign universities have to be ranked among the Global 500 in league tables approved by UGC from “time to time”; degrees awarded have to be on a par with country of origin; tuition fees have to be reasonable; faculty employed have to be on a par with country of origin; study programmes should not be contrary to sovereignty of India and should adhere to public order, decency and morality.

Consequent to this formal UGC notification, Deakin University, Australia became the first foreign university to establish a campus in the Gujarat International Finance Tec-City (GIFT City), near Ahmedabad.

EW comment. In a detailed Special Report ‘Half-hearted invitation to foreign universities’ (EW January 2024), your editors commented that “bristling with a gamut of discretionary rules, regulations and conditions, the UGC Regulations are unlikely to enthuse top-ranked foreign universities to establish owned campuses in India”.

“Even modest success of this foreign universities’ initiative requires UGC to loosen its regulatory grip and create inviting ground conditions to attract the world’s best foreign universities. For foreign, especially Anglosphere universities, institutional autonomy is a live and serious issue. India’s ubiquitous educracy needs to learn to respect this concept,” wrote your editors.

2024

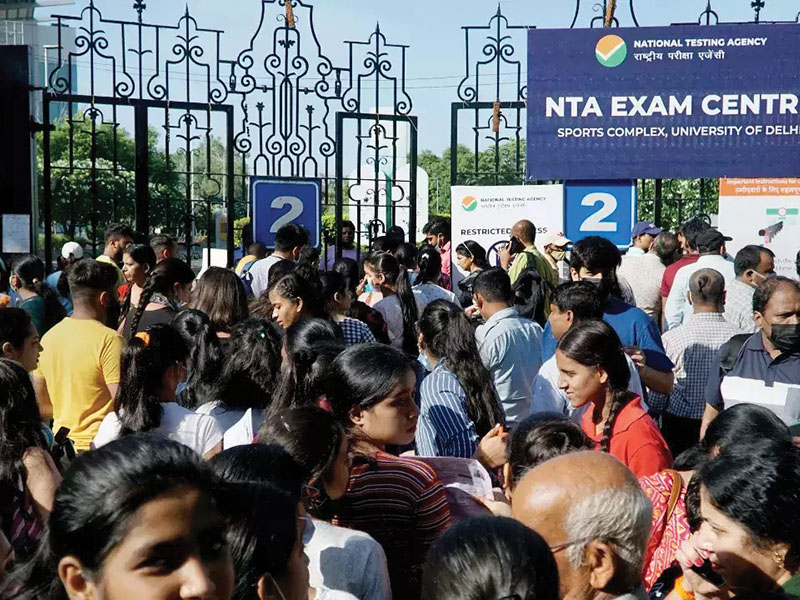

NEET exam scam. Results of NEET-UG (National Eligibility-cum-Entrance-Test-Undergraduate) 2024 — a centralised national exam for aspirant medical practitioners introduced in 2016 — were announced on June 4. Immediately thereafter, reports and evidence emerged of widespread exam malpractice including bribery of officials conducting and supervising this centralised exam written by 2.4 million school-leavers aspiring for admission into medical colleges countrywide. Following extensive public protests over NEET exam paper leaks, unprecedented grades inflation, and bribery, the NDA/BJP government constituted a high-level seven-member committee under the chairmanship of Dr. K. Radhakrishnan, former chairman, ISRO, to “quickly establish a robust tamper-proof exam system”.

EW comment. In an in-depth Special Report titled ‘Rectifying NTA exams disaster,’ EW reported on widespread cheating, favouritism and swindles in NEET-UG 2024 and suggested ways and means to fix this mess. “The scale and impact of the NEET-UG 2024 contretemps has again highlighted the sustained neglect of education and human resource development by successive administrations and the establishment. The NEET-UG scandal is the inevitable outcome of this national blindspot. It has shaken the faith and trust of students, parents and teachers communities in the country’s education system which has a long history of public exam malpractices because of capacity shortage across the spectrum. Restoring this massive loss of faith requires more than band-aid solutions from the BJP-led NDA 3.0 government which has begun its new shaky innings on the backfoot,” wrote your editors.

Dharmendra Pradhan’s second innings. On June 13 Dharmendra Pradhan was re-appointed education minister for a second term after the NDA coalition led by the BJP won a majority in General Election 2024. However within two weeks of his being re-appointed as education minister in the Modi 3.0 government, Pradhan has become embroiled neck deep in the NEET-UG exams scandal which jeopardised the future of 2.4 million school-leavers who wrote the exam.

Dharmendra Pradhan’s second innings. On June 13 Dharmendra Pradhan was re-appointed education minister for a second term after the NDA coalition led by the BJP won a majority in General Election 2024. However within two weeks of his being re-appointed as education minister in the Modi 3.0 government, Pradhan has become embroiled neck deep in the NEET-UG exams scandal which jeopardised the future of 2.4 million school-leavers who wrote the exam.

EW comment. In a detailed cover story titled ‘Dharmendra Pradhan’s second innings priorities’ (EW July), EW highlighted that though under Pradhan’s leadership the ministry has fast-tracked “some important recommendations” of the revolutionary NEP 2020, progress of implementation has been slow and constrained by inadequate budgetary outlays. “In his second innings which has got off to a shaky start, Pradhan needs to speak up forcefully in Union cabinet meetings for greater expenditure allocation for education which has to rise to 6 percent of GDP as recommended by the Kothari Commission way back in 1967 and promised in every BJP election manifesto,” wrote your editors.

Moreover your editors lamented that although “EducationWorld has published three lead stories featuring him on the cover, he has stubbornly refused to respond to important questions demanding accountability for progress of policy initiatives and directives emanating from Shastri Bhavan, Delhi.” We advised him to shed this “communication deficit” and invited “his cooperation in our common cause to provide high quality pre-school to PhD education to the world’s largest child and youth population, to enable India to attain a place of honour and respect in the comity of nations in the 21st century”.

End Note. The abridged history of Indian education recited above features the major milestones of the quarter century past as documented — and perhaps influenced — by EducationWorld. It’s important to note that during this epochal period, your editors have uninterruptedly published 289 editions of this sui generis news publication which translates into 17.34 million printed and curated words. On the occasion of our 25th anniversary, we once again call upon all right-thinking citizens in pre-primary to Ph D education, politics, bureacracy, business and industry to enable our mission to “make education and human resource development the #1 item on the national agenda.” Sine qua non.

It’s important to note that during this epochal period, your editors have uninterruptedly published 289 editions of this sui generis news publication

See www.educationworld.in Archives

Add comment