Multiple Maladies of Indian Sports

The 119-strong contingent of the second most populous (1.2 billion) country brought back only two also-ran medals from the Rio Olympics — substantially less than the six won in the XXX Olympics staged in London four years ago. Against this dismal performance, it’s revealing that the People’s Republic of China, which has a comparable size population and landmass, bagged 70 medals including 26 gold, and tiny Jamaica (pop.2.7 million) garnered 11 including six gold.

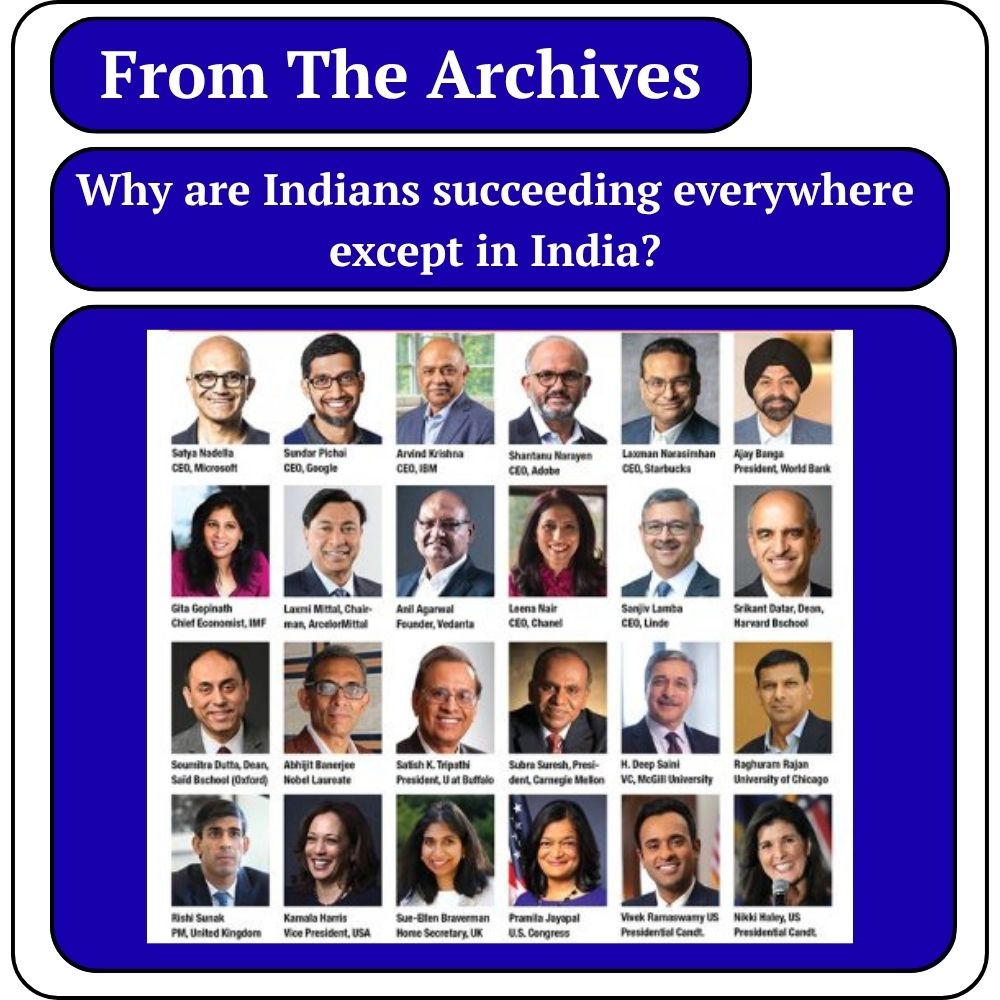

The most obvious cause of India’s inability to put its sportspersons on the global map, is the stranglehold of manipulative, sports-agnostic politicians and bureaucrats over sports and athletics organisations — most of them government-funded — countrywide.

Despite the autonomously-funded and administered Board of Cricket Control of India (BCCI) having nurtured and transformed the Indian cricket team into world champions and India into the Mecca of world cricket, and the Gopichand Badminton Academy, Hyderabad, promoted and managed by former All England champion Pullela Gopichand, training and developing world class women champions Saina Nehwal and P.V. Sindhu (the latter won a silver in Rio), neither the Centre nor state governments seem willing to decree that all government-funded sports organisations should be headed by eminent sportspersons.

Yet at the root of India’s disgraceful record in Olympic sports is woefully inadequate funding. In 2015-16, the annual budget of the Union ministry of sports and youth affairs was a mere Rs.1,541 crore, of which two-thirds is consumed by official salary and admin expenses, leaving minuscule amounts for disbursement to state governments and sports associations and federations. Against this the British government’s budget to prepare the kingdom’s 366 athletes for the Rio Olympics aggregated £350 million (Rs.3,220 crore).

Increased government funding apart, miserly corporate India also needs to learn from the US, where it’s commonplace for local industry and firms to combine business (brands promotion) with philanthropy by sponsoring school/collegiate sports tournaments. Public-private partnerships are crucial to building contemporary sports infrastructure enabling children and youth easy access to stadiums, gymnasia and playgrounds.

Even more important is an urgent need for managements of the country’s 1.4 million schools, 37,000 colleges and 744 universities to develop health, fitness and sports cultures. This requires a revolutionary mind-set change within the academic and parents’ communities to accept that co-curricular and sports education is as important as academics.

As a response to India’s Rio debacle, prime minister Narendra Modi has announced a ‘task force’ to prepare a comprehensive action plan for “effective participation” of Indian sportspersons in the next three Olympic Games — 2020, 2024 and 2028. But it’s doubtful whether government committees are the prescription for reviving Indian sports.

Add comment