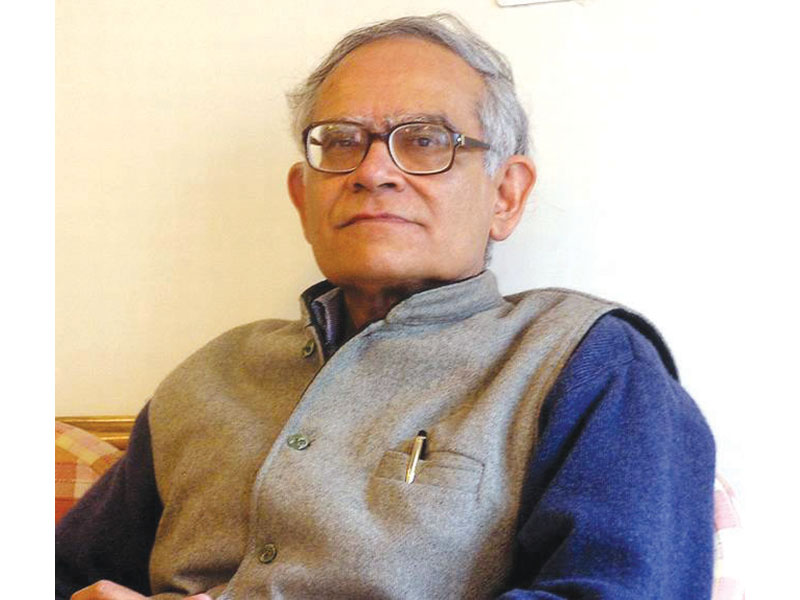

– Dr. Krishna Kumar is honorary professor of education, Panjab University, and a former Director of NCERT

The 200 questions that NEET-UG asks candidates to solve are multiple choice questions. Students drilled into speedy cracking of questions are certain to get high rank. What have these skills to do with becoming a good doctor?

This summer’s awful story of NEET (National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test – the centralised national exam for undergrad admission into the country’s 706 medical colleges, written by 2.4 million school-leavers in 2024) reveals how far things have gone in a wrong direction.

But the NEET story is merely a symptom of what has happened to our system of education. If you start from June 4 when NEET-UG results were declared, you can recognize all efforts made by the authorities and institutions to ignore grave lapses. When it became impossible to ignore protests, attempts were made to use adhesive tape to make things look normal.

The images of 18-year-olds protesting in New Delhi’s sweltering heat will not endure in the ever-changing world of the new digital media, but the troubles afflicted by NEET will. Can the expert committee appointed to look into them provide applicable solutions? Can the National Testing Agency (NTA) which conducts NEET and other entrance tests learn from the experience and improve itself?

These questions are not real, in the sense that they don’t reveal how deep the rot has penetrated. Even if NEET had delivered a result without convulsions, we would still be unsure if the successful candidates are better suited to pursue the medical practitioner’s career than those who did not succeed. The 200 questions NEET-UG asks candidates to solve at furious speed are like ones asked in any Multiple Choice Question (MCQ)-based exam. They are all drawn from the NCERT’s senior secondary level textbooks for three science subjects. If you ‘master’ (meaning, memorise) these textbooks, and if you’ve been drilled into speedy cracking of question items, you are certain to get a high rank.

What have these skills to do with becoming a good doctor? Will these skills help a medical practitioner maintain her devotion to the profession throughout a long career? Not really. All that NEET does is to offer a process to eliminate a vast number of candidates and arrange the rest into a ranked order.

It is no secret that success in NEET depends on being professionally coached. The legal battle for and against re-doing NEET is led by coaching institutions. In televised debates one saw several famous coaches of the different science subjects, but not one teacher from a regular higher secondary school. NEET and other competitive exams have pushed science school teachers to the margins. Schools have no choice but to allow students to attend coaching classes in school time, and NEET candidates seldom worry about (the school-leaving) board exam results. A few years ago, the IIT admission test allotted a certain percentage of marks to students’ board exam performance. Later, this arrangement was cancelled.

By usurping the school, NEET has rendered school curricular reforms irrelevant. In science, these reforms had focused on practical experimentation to encourage students to observe and think on their own. Coaching institutes have no place or time for labs or practicals.

Break-down of each item and relentless practice of solving questions asked in different verbal ways is the focus of teaching at a coaching institute. Thus, its dominance has damaged the quality of science learning at the institutional and individual levels. Does this affect the quality of learning in a medical study programme? Obviously it does, but no one talks about it. Studies made in the IITs have shown that the quality of project work and other activities has suffered as a consequence of the role of coaching in the selection of entrants.

Young people don’t know how far things have slid. To be young means to be unaware of the history in which your own life is wrapped. If coaching is the way to get into a medical career, so be it, say NEET aspirants. Their parents too see no better option. The government has accepted the clout of coaching institutes and recognised their contribution to the economy of towns like Kota.

The coaching industry has now absorbed a considerable number of the academically qualified but jobless youth of at least two generations as coaches. The industry also keeps the dream of professional careers and civil service alive for millions. The dream lingers on with repeated attempts at exams like NEET.

Incompetence and malpractice have muddied the NEET story this year. Yet the idea of an overarching exam — that too based entirely on MCQs — is flawed. Will it be rectified in coming years? Hard to tell. Generally, the system muddles along, and when it gets stuck, a lot of noise is made, giving the impression that radical reform measures will be taken soon.

That rarely happens and when the wheel is pulled out of fresh mud, the bullock cart carries on. This is hardly a cynical description. All it does is to remind ourselves that real reforms demand sustained critique and will.