No products in the cart.

Partitions history retold

Partitions history retold

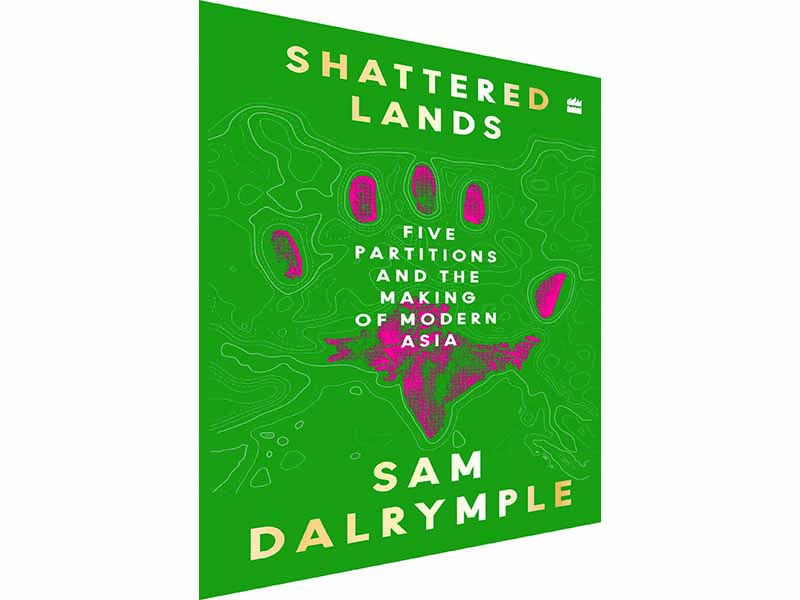

Shattered lands: five partitions and the making of modern asia

Sam Dalrymple

William collins

Rs.799 Pages 520

For a considerable period of time, historical studies on the Partition focused primarily on the role that key non-colonial actors, including the Indian National Congress, Muslim League, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah played in the days leading to the Partition. The part that the British colonial state played was relegated to the margins.

Moving away from this skewed perspective, historians, in more recent times, have made attempts to examine the pivotal, and at the same time dubious, role that the Mountbatten-led British Indian government played in dividing the country and its people on religious lines. Colonialists, given that all the instruments of power were in their hands, were majorly responsible for Partition as well as the mass displacement and bloodshed of 1947. Recent analyses have demonstrated conclusively that the British Indian government was determined to divide the country, with individuals like Mountbatten exerting immense pressure on colonial cartographers and officials to finish the ‘task’ at the earliest.

Historians studying the Partition of India have seldom tried to go beyond their area of research and study this human tragedy on a bigger scale. Comparative studies on the Partition are still few and far between. In light of this lacuna, young historian Sam Dalrymple’s new approach to the subject in his recent book Shattered Lands, becomes relevant.

Dalrymple draws attention to Partitions played out in different parts of Asia, including Burma, the Arabian Peninsula, Pakistan and Bangladesh. In addition to these, the complex issue of integration of the Princely States with India, Pakistan and Burma, has been termed as the ‘fourth partition’ by the author.

The source of all the five partitions was a political entity known officially as the ‘Indian Empire’ or ‘the Raj’. This study argues that till about the 1930s, the Indian Empire, comprising the region including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma, Nepal, Bhutan, Yemen, Oman, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait, was a political unit. However, within a span of barely 50 years, this entity, referred to as the crown jewel of the British Empire, collapsed, or, to use Dalrymple’s description ‘shattered’.

While most issues concerning partitions of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have been examined extensively, it is the detailed study of lesser-known separations of Burma and the Arabian Peninsula that makes the present work illuminating.

In a lengthy portion, the author outlines not only socio-political conditions which led to the separation of Burma from the Indian Empire, but also highlights fascinating details pertaining to inauguration of the new state. The challenges that emerged in the wake of this partition are thoroughly examined by the author. From mundane problems like release of a new set of stamps depicting the Shwedagon Pagoda instead of the Taj Mahal, to more complex issues concerning the demographic profile of India, the colonial state, in days following the political separation.

Among others, an important point that Dalrymple makes, with regard to this ‘first partition’ which occurred in 1937, is that by drawing partition lines between India and Burma, a ‘non-Hindu’ region, the British India government gave credence to the idea that India belonged primarily to Hindus, a claim reiterated by the right-wing Hindutva forces.

Along with Burma, the far-flung Aden region too was separated from the Raj in 1937. And this was also the year when the Congress adopted Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Vande Mataram as the national song of India. All these developments, according to the author, contributed towards alienation of a large number of Muslims, including Jinnah. These events acted as triggers for the Partition of India and Pakistan, which occurred merely a decade later in 1947. In fact, it may be suggested that Partition is an integral part of the British Empire’s legacy.

Analysing British perception of the Indian Empire, the author makes an interesting observation. He argues that primarily for diplomatic reasons, the colonial state played safe on the issue of describing the extent of the empire. Maps depicting the Raj in its entirety were almost always published in ‘top secrecy’. Regions such as Oman, Nepal, Tibet and a few Arab states bordering the Ottoman Empire never appeared in colonial maps. Indeed even though some of these places were separated from the Indian Empire in course of time, the uncoupling process was without large-scale violence.

On the other hand, states which comprised the core of the Empire — India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Burma, witnessed unprecedented bloodshed and displacement, in times of Partition. Shattered Lands stresses that the British-sponsored partition(s), rather than solving issues, complicated them further.

In this context the cases of Burma, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are very relevant. The problems that plagued these nations at the time of their formation continue to fester. The fact that issues concerning Kashmir, insurgencies, coups and unstable governments, have become more complicated over the years, has been well defined by the young historian.

Written in an easy and engaging style, Sam Dalrymple’s meticulously researched history refreshingly destroys the depiction that British imperialism was benign. That partition, rather than being a ‘simple’ and an ‘innocent’ political act, was ‘layered’ and a ‘shrewd’ tactic that the colonial state employed to achieve personal gains, is highlighted in the study.

Also, by delineating the rather long and tiring process of integration of princely states with India, Pakistan and Burma, Dalrymple is able to convincingly demonstrate that shattering of the ‘Indian Empire’ occurred at multiple levels, a fact rarely acknowledged.

The book does have its share of flaws. Given that Britain played a crucial role in sowing the seeds of discontent between Palestine and Israel, an account of what we may term as the ‘sixth partition’ is conspicuously absent.

Similarly, while the author touches upon the reign of Zia-ul-Haq in his recitation of the internal strife in Pakistan, following the death of Jinnah and the formation of Bangladesh, there is hardly any discussion on the atrocities that were inflicted on Communist intellectuals, including Faiz Ahmad Faiz, by the General’s government.

Dalrymple’s account of South Asia’s chaotic 20th century is vivid, incisive and expansive, all at once. Peppered with anecdotes and rare archival photographs, Shattered Lands is an unputdownable history of the collapse of the Indian Empire and the layered concept known as ‘Partition’. And for this the young historian should be commended.

Amol Saghar (The Book Review)

Post Views: 91

Add comment