No products in the cart.

Private varsities catalysing sea change in Higher Education

A spate of new genre private universities enabled by state government legislation and led by brilliant academics with excellent project management and leadership skills are generating overdue stir within the shady bowers of Indian academia, writes Dilip Thakore

IN THE LATEST (NOVEMBER) WORLD University Rankings (WUR) 2023 of the London-based Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) and Times Higher Education (THE), the authoritative rating/evaluation agencies of higher education institutions worldwide, India’s most reputed universities which top domestic league tables, including the Union education ministry’s NIRF (National Institutional Ranking Framework), the annual EducationWorld India Higher Education Rankings (EWIHER), India Today rankings, among others, are ranked way down near bottom.

In the QS WUR, only three Indian universities — the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore (IISc, estb.1909); Indian Institute of Technology-Bombay (IIT-B, estb.1958) and Indian Institute of Technology-Delhi (IIT-D, estb.1961) are ranked among the Top 200 worldwide in that order with IISc ranked #155. In the THE global league table which gives greater weightage to research and citations, IISc is awarded a ranking of 251-300 (institutions ranked below the Top 200 are not awarded a precise rank) followed by the JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Mysuru and Shoolini University of Biotechnology & Management, Solan (Himachal Pradesh) awarded 351-400 ranking.

On the other hand, China’s Peking University is ranked #12 and Tsinghua University #14 by QS with eight Chinese universities ranked among the QS global Top 200. In the THE WUR league table 11 Chinese universities are ranked in the Top 200. Moreover several South-east Asian universities including Seoul National, Yonsei, Korea Academy of Science & Technology and five others are ranked among the THE Top 200 as are four in Japan. In the QS WUR 2023, eight South Korean universities are ranked among the Top 200 cf. India’s three and ten in Japan. Even Malaysia, a late-comer in higher education, has four universities in the QS Top 200 league table. Against this, it’s pertinent to note that the Indian Institute of Science was established in 1909, and the Bombay, Madras and Calcutta universities admitted their first batches in 1857.

[userpro_private restrict_to_roles=

Clearly, successive governments in New Delhi and state capitals — all the Indian universities listed above are public, i.e, government administered institutions of higher learning — have blown the early movers advantage that India had in higher education. This dismal conclusion is supported by the depressing fact that India’s academy has not produced a science/technology Nobel Prize winner since Sir C.V. Raman conducting research in Calcutta University was awarded the physics Nobel in 1930 for research studies in the phenomenon of light scattering. The only other Indian to be awarded a Nobel Prize for studies conducted in India is Rabindranath Tagore for literature in 1913.

The failure of India’s public universities to cash their early movers advantage is also testified by the grim reality that not a single major world-beating invention — computer, Internet, cell phone, jet aeroplanes, motor car etc — has emerged from the country’s universities whose number has risen to 1,072.

Some successes have been claimed in agriculture productivity by a dozen universities grouped under the banner of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, who claim they are the authors of India’s much trumpeted Green Revolution which has quintupled foodgrains — rice and wheat — production in India from 50 million tonnes per annum in 1950 to over 250 million tonnes currently. But the weight of evidence indicates that the primary research into developing a new genre of high-yield, disease resistant semi-dwarf Mexican wheat strain was conducted by American agri-scientist Dr. Norman Borlaug in Mexico and adapted to Indian soil conditions by ICAR-affiliated universities.

However despite the success of the Green Revolution (critics allege it has severely damaged soil quality across large swathes of rural India because of its heavy reliance on chemical fertilisers), the on-ground reality is that wheat yields in India are 4 tonnes per hectare cf. 6/h in China and Egypt and New Zealand’s 8/h and 9/h respectively. Moreover, ICAR with its head office in Krishi Bhavan, Delhi, has transformed into an inaccessible fortress and its admittedly superbly equipped affiliated 75 universities whose model farms report high per hectare yields, have almost abandoned field extension work. They have morphed into citadels of well-remunerated faculty engaged in esoteric research which seldom translates into widely disseminated farm practices. In 2020, when your editors published a detailed lead feature to investigate the track record and research dissemination practices of ICAR, the council’s top brass — despite the council being a publicly funded agriculture research and education institution — resolutely declined all interview and access requests (see https://www.educationworld.in/indias-ivory-tower-agriculture-universities/).

The standard excuse of Indian academics and education ministry mandarins for the dismal ranks awarded to India’s universities by the authoritative QS and THE (as also the well-respected Shanghai Jiao Tong) league tables rating and ranking the world’s best 1,500-plus universities, is Indian exceptionalism.

The QS and THE evaluation parameters don’t accord any weightage to access and inclusion which is a priority of Indian universities. Moreover they give too much weightage to research, whereas Indian universities primarily tend to be teaching institutions because under the indigenous higher education system, high research falls within the purview of the Central government-funded Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR, estb.1942). Unfortunately the breakthrough research record of the politics infested Soviet-inspired CSIR which has established 37 labs across the country, is even worse than of India’s globally low-ranked universities.

DISMAL QUALITY HIGHER Education dispensed by the overwhelming majority of India’s universities — only 10 percent of the country’s 1,072 universities ranked in the annual EW India Higher Education Rankings provide globally benchmarked study programmes — explains why the number of Indian students enrolling not only with American, British, Australian, Canadian, but also with higher ed institutions in non-English speaking countries, has risen to record numbers, despite foreign universities continuously raising tuition, residential and other fees. In November, the number of Indian students admitted into British universities at 127,731 was the largest foreign cohort, surpassing the number from China for the first time. Likewise, over 199,462 Indian students were admitted in US universities, with the unnerving prospect of the majority never returning.

With addle-headed leftists having dominated — and continuing to dominate — the academy and higher education since independence, India’s universities have been rendered rudderless by multiplicity of objectives. The prime objective of the university — to pursue academic excellence and generate new knowledge through serious research — has become obscured. Instead, the academy has become a provider of well-remunerated sinecures for left and left-liberal ideologues who have given ‘inclusion’ and ‘equity’, rather than academic excellence, highest priority.

Thus over the years, reservation of 15 percent and 7.5 percent admission quotas for students (and often faculty) from historically deprived scheduled castes and tribes, have been gradually increased by reserving 27 percent for OBCs (other backward castes/classes) and latterly another 10 percent for EWS (economically weaker sections) in the general category.

Therefore with almost 60 percent of students admitted under criteria other than merit, the prime purpose of universities — pursuit of higher education excellence — has been lost. Hence the continuous — and accelerating — exodus of students to institutions of education abroad.

“The major infirmity of higher education in India is continuous under-investment in public education and discouragement of private investment in higher education. Relative to our 1.4 billion population, the number of higher ed and professional institutions is much too few. India has a GER (gross enrolment ratio) of only 26 percent in higher education against 60 percent in the US and European countries, and 85 percent in South Korea. This means that only one of four youth in the 18-24 age group is in higher education. Against this backdrop, it’s a very positive development that large numbers of private universities are mushrooming across the country. However, most of them are in the liberal arts and humanities space whereas the pressing demand is for science, technology and medical education. Against the 1.5 million school-leavers who write the IIT-JEE exam, a mere 30,000 toppers are admitted by the country’s 23 IITs, and NITs. Therefore tens of thousands of aspirational school-leavers with good board exam results are forced to apply to foreign universities. Moreover, most foreign universities offer the advantage of graduates being allowed to work in their host countries for a few years. This enables students to pay off a substantial part of their loans or accumulate savings. That’s why the accelerating outflow of students from India,” says Atul Thakkar, the Mumbai-based vice president of Anand Rathi Ltd and head of the company’s substantial education advisory practice.

Decades of under-investment in education — despite the high-powered Kothari Commission recommending a minimum of 6 percent of GDP in 1967, the annual outlay for public education (Centre plus states) has averaged 3.5 percent — and packing higher education institutions (HEIs) with non-merit students and faculty to attain social justice objectives, has diluted the quality of education in the country’s once hallowed universities.

This sin has been compounded by universal over-subsidisation of higher education. Tuition fees in the country’s public HEIs have remained frozen for decades and contribute 5-6 percent of institutional revenue against the global average of 20 percent. Moreover, fee subsidies in public HEIs are universal, rather than targeted, permitting the middle and elite classes to derive undue advantage. The issues of universal over-subsidisation of tuition fees and under-investment have been consistently obfuscated by Left academics who have benefitted from this iniquitous system which has not only diluted the value and quality of education in HEIs, but also continuously under-funded the country’s 1.02 million government primary-secondary schools.

With acceptable standards of teaching-learning and research restricted to at best 10 percent of the country’s 1,072 universities, the rush of students from the expanding middle class to well-funded and quality-conscious HEIs abroad is hardly surprising. Vineet Gupta, promoter-director of the Delhi-based Jamboree Education Pvt. Ltd (estb.1993), one of the country’s largest test prep companies for foreign universities, identifies too-few globally comparable domestic HEIs, for which admission competition is too intense and conducive conditions in the academy and liberalisation of post-graduation work rules in Western countries as the prime attractions of study abroad. An alumnus of IIT-Delhi, Gupta is highly knowledgeable about the higher education scenario in India and abroad. Jamboree Education trains 20,000 students per year for admission into universities abroad.

WITHIN INDIA’S FAST-expanding middle class, high-quality education is a common aspiration. And the plain truth is that acceptable quality education is a big issue with India’s HEIs and universities. Only a few dozen offer globally benchmarked education for 160 million children and youth in the 10-19 age group. Against this backdrop, the emergence of a substantial number of private universities has prevented a crisis in Indian higher education. The best new millennium private universities offer globally comparable faculty, study programmes and infrastructure, and have completely transformed India’s higher education landscape. We need at least 200 more of them,” says Gupta, an early co-promoter of the highly ranked liberal arts Ashoka University, Sonipat (estb.2014) and science and technology focused Plaksha University, Mohali (2021).

Even if somewhat belatedly, accelerating winds of change are blowing over post-independence India’s higher education sector ruined by continuous control-and-command exercised by the omniscient neta-babu brotherhood comprising ill-educated politicians and IAS generalists who insist on supervising and monitoring even highest qualified academics and educationists. Fortuitously in the new millennium, a latter-day triumvirate of intelligent lawyers, private education entrepreneurs (edupreneurs) and state governments discovered that education is a ‘concurrent’ subject under the Constitution, i.e, the Central and state governments can enact education legislation. With states confronted with a ballooning problem of youth unemployment, beginning to compete furiously to attract investment in industry and business, especially in the new age ICT (information communication technologies) sector, ready availability of well-educated human resources has become a necessary precondition.

With poorly educated graduates of colleges affiliated with over 460 state government universities increasingly being rejected by industry, in 2017, under pressure from state governments the Delhi-based UGC (University Grants Commission) — the apex administrative body supervising non-technical higher education countrywide — issued a guideline permitting well-reputed, high-performing colleges granted academic autonomy (by UGC) to introduce new employment-oriented study programmes with substantial freedom to prescribe syllabuses, design curriculums, recruit faculty and levy market-determined tuition fees.

This liberalisation firman of UGC is a divinely inspired initiative which has the potential to transform over 1,000 autonomous colleges affiliated with state government universities, says Balkishan Sharma, a Mumbai-based visionary education consultant who has pioneered introduction of contemporary, employment-oriented degree programmes in a rising number of autonomous undergraduate colleges countrywide.

“For several decades, undergrad colleges affiliated with state universities have been offering generalist arts, science, commerce and engineering programmes, which, although they provide students basic knowledge of literature, the humanities, science and engineering, don’t ready them for employment. After UGC issued the new liberalisation guidelines to autonomous colleges five years ago, several autonomous colleges have introduced well-designed degree programmes such as BBA (bachelor of business administration) which offer marketing, sports and events management and entrepreneurship as majors. In the science stream, they offer integrative nutrition and dietetics and in engineering, majors in AI (artificial intelligence) and data science. These degree programmes designed by experienced academics working in close collaboration with industry leaders, prepare employment-ready graduates who are quickly snapped up by industry. Now with the new National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 committed to granting autonomy to all undergrad colleges in a phased manner, they will be able to introduce jobs-oriented study programmes and compete with private universities. This is a very welcome development,” says Sharma, a highly qualified commerce graduate of Mumbai University and IIM-Ahmedabad, who has enabled introduction of new innovative programmes in Nagindas Khandwala, B.K. Birla College (Kalyan) and Ramanand Arya DAV College, autonomous colleges affiliated with Mumbai University. The first batch of 500 graduates of these courses have been “readily accepted” by industry, adds Sharma.

NEP 2020 is not only likely to give a new lease of life to state universities but also to the country’s 45 Central government varsities which after decades of infantalisation, have been awarded substantial latitude to enter into foreign academic and research collaborations.

Way out in the rural hinterland of Bihar, a new Nalanda University (NU) — successor of the ancient University of Nalanda which was a global centre of learning in the 5th century — promoted by the Central government in collaboration with 17 Asian countries and “envisaged as an icon of the new Asian renaissance: a creative space that will be for future generations a center of inter-civilisational dialogue”, is assuming shape and form. NU has had a slow start because of political and funding problems — including the resignation in 2015 of founding chancellor and economics Nobel Laureate Dr. Amartya Sen, citing “political interference in academic matters”.

However, Dr. Suanaina Singh, an English and comparative literature postgrad of Osmania University and former vice chancellor (2012-17) of the highly-respected English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, appointed vice chancellor of NU in 2017 is satisfied with the progress of this monumental project for which the Centre has allocated Rs.900 crore over the past five years.

“Five years ago, the 455-acre NU campus in Rajgir housed two porta cabins. Today our sustainable ecology campus with a built-up area of 2.25 million sq. ft is 95 percent complete and 250 students of our 700 registered students from 32 countries are on campus in globally benchmarked residential accommodation. Moreover, five schools and three research centres offering liberal arts and science projects are operational with scholars researching 50 projects and assignments. We are determined to build a solid foundation for NU to which students are returning after an interregnum of almost 1,000 years. I am very confident about the future of this high-potential higher education project,” says Dr. Singh.

ALTHOUGH WINDS of change are blowing across Central and state higher education campuses, reform and contemporisation of government HEIs steeped in dead habit and hobbled by vested interests is likely to proceed at glacial pace. On the other hand, the pace of reform, teaching-learning innovation and global benchmarking in the country’s new genre new millennium HEIs is fast and furious. And contrary to popular belief, 70 percent of India’s institutions of higher education are privately-promoted. Academically and financially independent and fully empowered by their host state governments, India’s new genre post-liberalisation private universities are catalysing a teaching-learning and research revolution that at long last offers real promise to meaningfully develop India’s abundant human resource, a prerequisite of national development.

A case in point is the O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana (JGU, estb.2009). Within 12 years of admitting the first batch of 100 students into its law school, this fast track university promoted with an initial endowment of Rs.500 crore (going on to Rs.1,500 crore) from steel tycoon Naveen Jindal, has acquired national and global reputation. Currently, JGU is ranked India’s #1 private liberal arts university by EducationWorld and #1 private varsity

by the London-based Quacquarelli Symonds (QS). Over the past decade, the number of students has grown to 10,000 mentored by 1,000 faculty, including 115 highly-qualified professors drawn from 48 countries. Moreover the number of schools — law, humanities, business management, international relations among others — under the JGU umbrella has multiplied to 12 providing 50 undergrad and postgrad degree programmes even as this young private university has signed academic exchange and research collaboration agreements with 375 universities in 67 countries worldwide. Evidently, the varsity’s management takes the descriptive ‘global’ incorporated into its title, seriously.

Dr. (Prof.) C. Raj Kumar, a polymath alum of Delhi, Oxford and Harvard universities and founding vice chancellor who has catapulted JGU into a globally respected law and liberal arts university in record time, is “totally bullish” about the future. “NEP 2020 is an enabling policy charter which has conferred real autonomy on HEIs — especially universities designated institutions of eminence by the Central government — by removing hurdles and impediments. After recently introducing a new Masters programme in public health and five online degree programmes with Coursera and Upgrad, we are stepping up our research activity — during the pandemic, our faculty wrote a record 800 papers cited in the globally respected Scopus Index. Now we are focused on designing new age interdisciplinary degree programmes while shifting our international academic collaborations focus from the West to universities in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America,” says Raj Kumar.

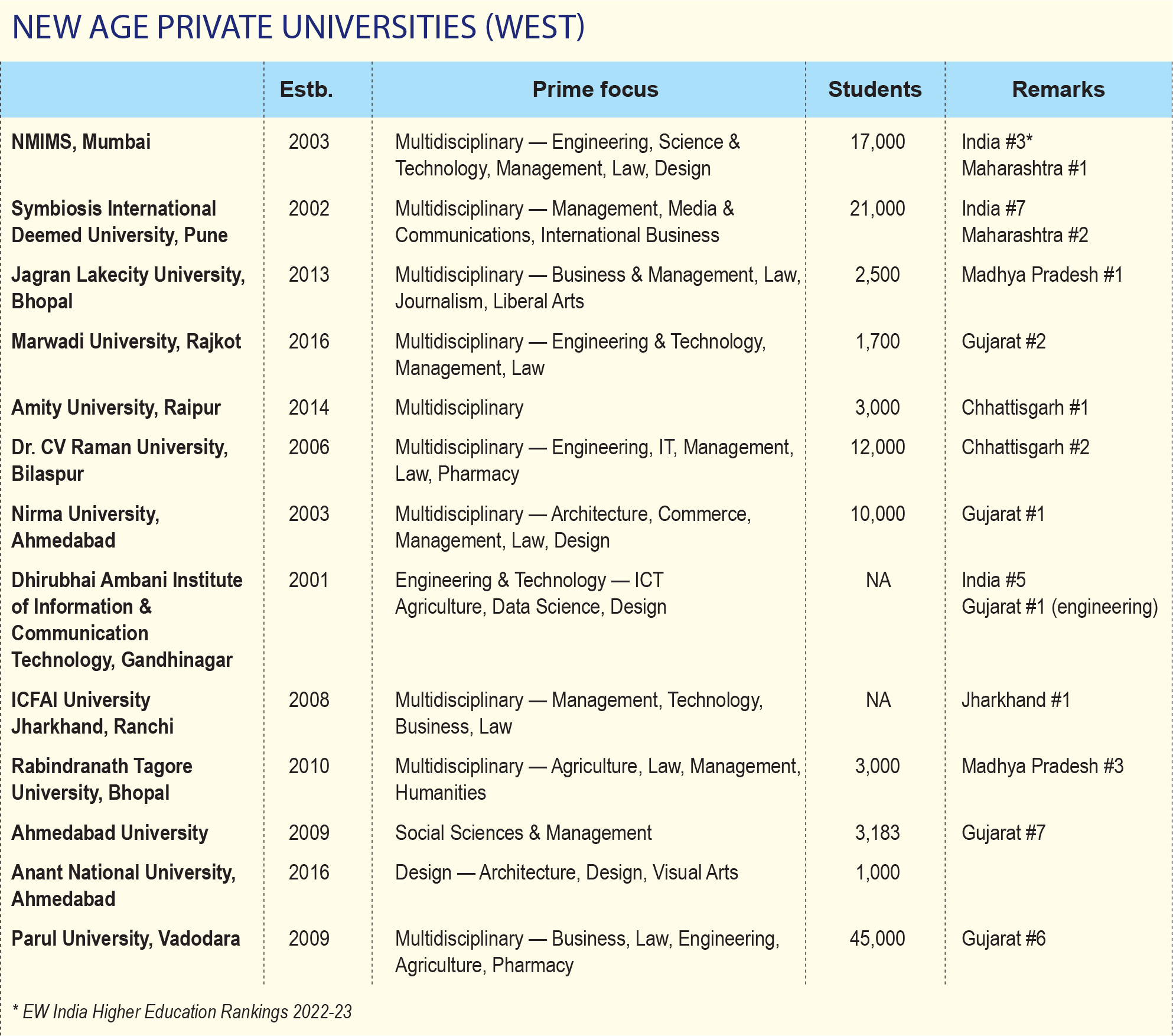

Undoubtedly following presentation of NEP 2020 to Parliament and the nation in July 2020, there is a discernible new buzz in Indian education — especially in higher education. In quick time dozens of contemporary private universities enabled by state government legislation and led by brilliant academics with excellent project management and leadership skills are generating overdue stir within the shady bowers of Indian academia. Even as private liberal arts institutions such as Ashoka, Jindal Global, Krea, Anant among others have quickly established national reputation, science, technology, skills universities necessary for transforming India’s predominantly agriculture economy into a modern manufacturing and digital services driven nation, are also springing up countrywide.

FOR INSTANCE, THE crowd-funded Plaksha University, Mohali (PU, estb.2021), which bills itself as India’s first technology university promoted after the 23 IITs (Indian Institutes of Technology). This mint new state-of-the-art digital technologies driven fully-residential private university established at a project cost of Rs.850 crore on a 50-acre campus in Mohali (Punjab) has 250 students and 30 faculty in four new-age interdisciplinary study programmes — computer science & artificial intelligence; cyber security systems; biosystems engineering and data sciences, economics and business.

“These future-oriented interdisciplinary study programmes have been ideated and designed with inputs from some of the world’s most respected academy and industry leaders, to prepare professionals equal to resolving several grand challenges confronting humankind — digital agriculture, health, water security, clean energy and climate change. On December 17, we celebrated Founders Day and I was very pleased to announce that we have enrolled students in all these programmes. Project Plaksha is being rolled out smoothly; everything is going according to plan,” says Dr. (Prof.) Rudra Pratap, an alum of IIT-Kharagpur, Cornell (USA) and former faculty at the top-ranked Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore (1996-2021), appointed founding vice chancellor of this ambitious, high-potential technology university earlier this year.

By all indicators the northern border state of Punjab in which successive state governments have been proactive to make up for lost time, is fast emerging as a hub of new age private universities. Another high-potential private HEI established by special state legislation is the Chandigarh-based Chitkara University, Punjab (CUP) ranked among India’s Top 10 private universities and #1 in Punjab (pop. 29.6 million) in the latest EducationWorld India Higher Education Rankings.

Promoted in 2002 as the Punjab Technical College, it rapidly transformed into a college of professional education (engineering, pharmacy, business management, nursing, hospitality etc) and was awarded university status by the state government in 2010. In 2008, the government of Himachal Pradesh, established the affiliated Chitkara University Himachal through special legislation. Currently the two private universities have 20,000 students mentored by 1,552 well-qualified faculty.

“I am very satisfied with the progress and development of CUP in particular during the past decade. We have been awarded A+ grade by NAAC; Platinum Ranking by the London-based QS; ranked # 2 among private universities under the Central government’s Atal Innovation Mission and #3 under the Swachhata campus cleanliness mission, and last but by no means least, Punjab’s #1 private university and #2 in Himachal and among the national Top 10 by EducationWorld. Currently we are focused on implementing the National Education Policy by introducing schools of liberal arts and converting both our institutions into multidisciplinary universities. Moreover we have signed academic and joint research collaboration agreements with 180 universities around the world and are rapidly transforming our institutions into global research hubs. The future is very bright and promising,” says Dr. Madhu Chitkara, an alumna of Delhi and Punjab universities and pro chancellor of CU, Punjab and Himachal.

DOWN SOUTH WHERE education institutions promoted by successful businessmen and industry leaders is a well-established tradition, highly-respected real estate tycoon Dayananda Pai, promoter-chairman of Century Real Estate Holdings Pvt. Ltd, has established the ambitious Vidyashilp University, Bengaluru (VU, estb.2021) which admitted its first batch of 74 students mentored by 16 faculty into its School of Computation and Data Sciences last August.

Graduates of this initial four-year study programme will be awarded degrees in data sciences or a unique decision sciences programme at their option. “With industry, business, services and entertainment the world over going digital, it’s very important for universities to provide students radically different, innovative study programmes to enable them to succeed in increasingly digitalised workplaces. Therefore, all our programmes will be interdisciplinary and digitally-enabled. For instance our next initiative, the Vidyashilp Business School will offer digital business as major and minor subjects. Fortunately under NEP 2020, universities have been granted substantial autonomy under liberal guidelines. Our goal is to develop our students into highly competent digital technologies savvy, conscientious citizens aware of their individual and social responsibilities,” says Dr. Vijayan Immanuel, founding vice chancellor of VU.

An alumnus of NIT-Suratkal and the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, with 22 years (1984-2006) teaching experience in NIT-Suratkal followed by hands-on industry experience in blue-chip IT major HCL Technologies (2006-11) and short stints with IMS Unison (Dehradun) and Presidency (Bengaluru) universities, with his near-optimal mix of academia and industry experience, Immanuel seems the best possible choice to get VU promoted with a corpus of Rs.600 crore, up and running quickly. “Twenty first century youth are digital natives who take naturally to exploratory, experiential learning. VU will incrementally evolve into a multidisciplinary university driven by cutting-edge technology,” he promises.

Climate change in the education sector catalysed a combination of factors — emergence of new can-do tribes of edupreneurs, philanthropists, state government leaders competing for industry and business investment, not least EducationWorld which has been evangelising improved learning outcomes from preschool to Ph D — have not only stimulated business and industry leaders, but edupreneurs already invested in education to expand their footprint and operations.

An exemplar is Sanjay Padode, alumnus of the blue-chip BITS-Pilani. In 1995, Padode founded and nurtured the AACSB (USA)-accredited IFIM Business School, Bengaluru (rechristened the Jagdish Sheth School of Management aka JAGSOM), routinely ranked among the country’s Top 15 private B-schools by EducationWorld and #2 in Karnataka. In 2019, Padode took a giant leap forward to promote Vijaybhoomi University — “a unique multidisciplinary liberal arts professional courses university” — on a scenic 200 acre fully-wired campus in Karjat, a two-hour drive from Mumbai. Although its smooth take-off was impeded by the Covid lockdown of almost two years, Vijaybhoomi has taken wing. Currently, it has 340 students enrolled in its two-year foundational liberal arts programme.

“The curriculum offered by Vijaybhoomi U for liberal professional education is unprecedented and unique in India. After a wide and strong two years common foundational programme, our students can study two majors and two minors in disciplines of their choice. Thus a student can graduate with a BBA (bachelor of business administration) degree combining widely disparate subjects such as business, AI, music and data science. Similarly a B.Tech student can combine AI, design, music and business. Our objective is to allow students total freedom to study subjects that interest them, so that they have an enjoyable and fulfilling higher education experience. By investing learners with the power of choice we have transferred authority from the university to students,” says Dr. Atish Chattopadhyay, founding vice chancellor of Vijaybhoomi U.

A business management graduate of Aligarh Muslim University and Indian Institute of Social Welfare & Management, Kolkata, Chattopadhyay has a wealth of experience in industry (Oberoi Hotels, Bakery Chain Kolkata), and B-schools (ICFAI, S.P. Jain, MICA, IMT, Ghaziabad and IFIM/JAGSOM).

QUITE CLEARLY, THE proliferation of new genre private universities in the new millennium has catalysed a sea change in India’s education landscape dominated by less than 100 Central universities, IITs, IIMs providing acceptable quality education to a small minority of privileged students, and 460 state government universities routinely certifying millions of under-prepared, and largely unemployable graduates.

Suddenly the higher education scene has come alive with a spate of shiny new and well-equipped liberal arts, science and technology and business management HEIs offering globally benchmarked degree and postgrad study programmes and research facilities. Although disparaged by Left ideologues and academics who despite the collapse of communism around the world, continue to dominate the Indian academy, India’s new genre private universities are here to stay offering the exciting prospect of nurturing the world’s largest and enthusiastic youth into a high productivity workforce.

Yet even as the bullish sentiment is pervasive in India’s 42,000 junior and undergrad colleges and 1,072 universities and sundry HEIs buoyed by the rapid success of the country’s new millennium private universities which have emerged as globally competitive institutions of higher learning, it’s pertinent to bear in mind that at the heart of NEP 2020 which is being acclaimed as the magna carta — charter of liberty — of higher education, there is a dangerous contradiction.

Although proclaimed in trendy, liberal lingo, NEP 2020 mandates establishment of four government-promoted supervisory organisations— the apex HECI (Higher Education Commission of India) and four verticals, viz, NHERC (National Higher Education Regulation Council); NAC (National Accreditation Council); HEGC (Higher Education Grants Council), and GEC (General Education Council) to ensure “light but tight” regulation of higher education institutions countrywide.

On the other hand, NEP 2020 promises substantial institutional autonomy by phasing out the colleges affiliation system and gradual conversion of undergrad colleges into autonomous universities with degrees awarding power. Simultaneously, the charter makes the right noises about awarding high-performance private and public universities and HEIs wide latitude in signing foreign collaboration and student and faculty exchange programmes, and determining admission and tuition and other fees.

Therefore the question arises: if provision of education is indeed devolved upon educators, what purpose will the elaborate supervisory super-structure serve? The answer to this question will determine whether the promising sea change in higher education catalysed by India’s new genre private universities will prove to be real or illusory.

Add comment