Seven out of 10 schools in India private: UNESCO

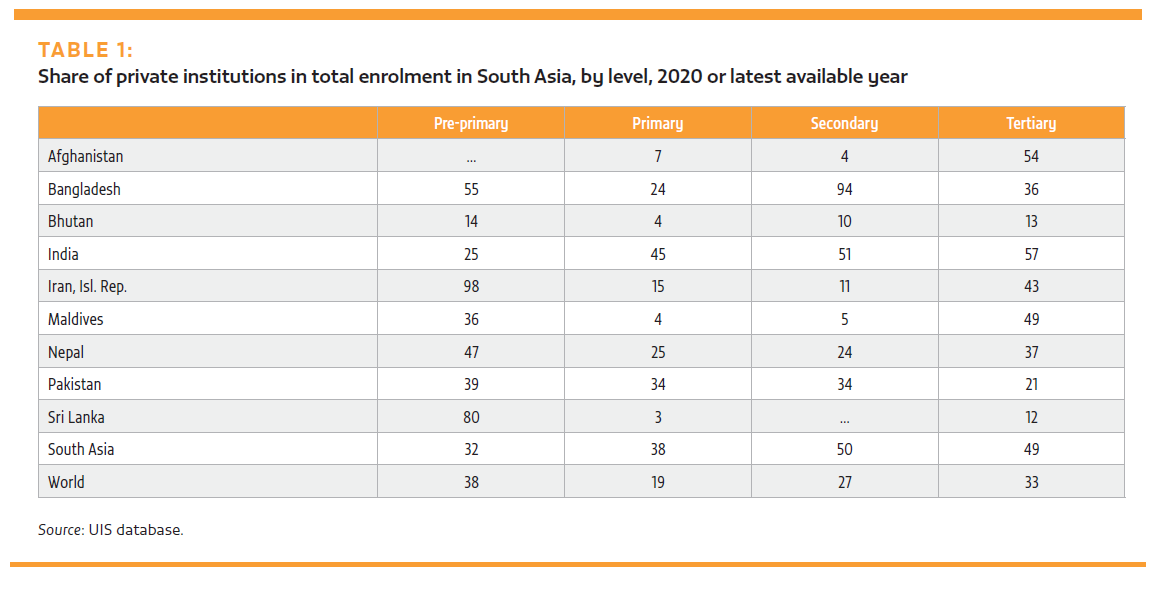

Private education in South East Asia has experienced rapid education expansion and are more involved in every aspect of education systems than in any other world region, according to a UNESCO report. Out of all new schools established in India since 2014, seven out of 10 are private independent schools. In Bangladesh, a quarter of primary and almost all secondary school enrolment is in private institutions.

Highly competitive examination pressures and dissatisfaction with public schools have led to the highest levels of enrolment in private institutions in primary and secondary education than in other regions, but also to extensive private tutoring and an explosion of education technology companies, says the report.

In early childhood, the private sector is often the main provider, educating 93 per cent of children in the Islamic Republic of Iran. At the primary level, private schools educate a quarter of students in Nepal, over a third in Pakistan and almost half in India. Low-fee private schools have flourished. International schools have grown alongside the demand for English-language education, effectively doubling in Sri Lanka between 2012 and 2019.

With fragmented systems stretched during the pandemic, and evidence of a shift of students from private to public schools, the report calls for a review of existing regulations on private institutions and how they are enforced. While access to education has grown faster than in any other region in the past few decades in South Asia, learning levels are more than one-third below the global average and growing more slowly than in the rest of the world. It recommends that all state and non-state education activities be viewed as part of one system, supported and coordinated ministries of education so that quality and equity can be improved.

Combining the experiences of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, it looks at occasions where the growing advent of private education has put equity under pressure but also at positive practices that have created cohesion across all actors involved.

Tertiary education is increasingly private due to insufficient public supply, covering over half of enrolment in Afghanistan by 2020. In Nepal, the limited capacity of the main public university in the country led to the establishment of non-state campuses. Teacher training institutions are also often private with teacher education only provided exclusively by the state in two countries, Bhutan and the Islamic Republic of Iran. In 2020, more than 90% of recognized pre-service teacher education institutions in India were privately funded through student fees.

Competitive education systems and labour markets have led to a surge in private tutoring, putting pressure on household finances. In Sri Lanka, the percentage of households spending on private tutoring increased between 1995 and 2016 from 41 per cent to 65 per cent of urban households and from 19 per cent to 62 per cent of rural households; it increased in Bangladesh between 2000 and 2010 from 28 per cent to 54 per cent in rural areas and from 48 per cent to 67 per cent in urban areas. The popularity of private tutoring has led to a rise of coaching centres; in India, their number may run into the hundreds of thousands.

Manos Antoninis, director of the report said “There is no one way of designing an education system. The call this report makes does not cast judgement on what system to choose, but on how that system is shaped. Millions of children at this point would have no education at all if non-state actors had not arrived to fill the gap. But a magnifying glass should be put upon the arrangements so that the balance does not tip towards profit-making and business interests and away from the interests of the child.”

In South Asia, households account for the largest share of total education spending (38%) among all world regions. Their share is particularly high in Nepal (50%), Pakistan (57%) and Bangladesh (71%). In 2017-18, average household expenditure per student attending a private-unaided school in India was over five times than that spent on a student attending government school. In addition, 13% of families saved and 8% had to borrow to pay for school fees. In Bangladesh, around a third of families borrowed money for their children to study at private polytechnics.

Antoninis continued: “A large part of the reason for the growth of private education in the region is the fact that governments spend far less than the recommended 15% of total public expenditure on education. But this leaves a ticking bomb for the poorest who are increasingly faced with high costs to access an education that should normally be free. We hope this report will act as an urgent call for reflection on how we are building education systems and who is missing out.”

Also Read: More than 80 million children will still be out of school by 2030: UNESCO

Add comment