South Africa: Must Fall protests report

Debates over the legacy of colonialism on South African campuses have been reignited by recent publication of a report examining the impact of anti-fees and anti-racism protests that rocked the University of Cape Town (UCT).

Debates over the legacy of colonialism on South African campuses have been reignited by recent publication of a report examining the impact of anti-fees and anti-racism protests that rocked the University of Cape Town (UCT).

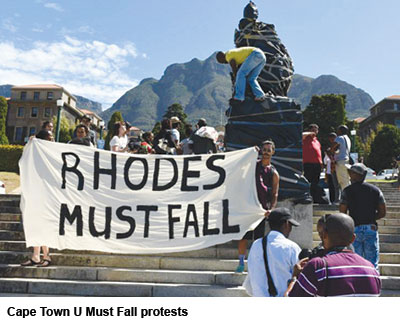

The Institutional Reconciliation and Transformation Commission, which produced the report, was created in the wake of the Rhodes Must Fall protests — which resulted in the removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes from Cape Town’s campus in 2015 — and the Fees Must Fall protests of 2016, which sparked protests across South Africa and ultimately resulted in the abolition of fees for poorest students.

The initial protests triggered a worldwide debate about the status of university monuments that are perceived to be tainted by racism or colonialism. Closer to home the protests had “a devastating impact on individuals, their families and communities, as well as the academic community as a whole”, according to the report. The report says many students who were involved in the protests have been suspended or expelled, with criminal charges brought against some, actions that had particular impact on students who were first generation learners.

It adds that the impact on the academic community was “most shocking”, with the protests causing divisions and cleavages along racial lines, and an overall “atmosphere of mistrust” among staff and between staff and students. The commission concludes that racism “does exist at UCT”, going beyond attitudes and into institutional practice. “Submissions are rife with stories of better-qualified black academics being passed over for employment and promotion in favour of white academics,” says the report.

Tiri Chinyoka, acting chair of Cape Town’s Black Academic Caucus, told Times Higher Education that the assessment is “100 percent correct”. “Institutional and structural racism, as well as unjust discrimination, victimisation, and other forms of structural violence have been and continue to be our lived experience at UCT,” says Dr. Chinyoka, a member of Cape Town’s department of mathematics and applied mathematics. “Unfortunately, the university does not seem to be doing anything tangible to tackle the issues raised in the report,” he adds.

However, Belinda Bozzoli, South Africa’s shadow higher education minister, criticises the report for being “conceptually weak and politically correct to a fault”. “It seeks to apply the notion of ‘restorative justice’ in a setting where serious and often violent infringements were committed by students on academic freedom, artistic freedom, personal freedom and the stability of one of the most revered academic institutions in Africa,” says Prof. Bozzoli, a former deputy vice chancellor (research) at the University of the Witwatersrand.

(Excerpted and adapted from The Economist and Times Higher Education)

Add comment