State of India K-12: Resilience Amidst Uncertainties 2024 Report: bright future for private school education

Against the backdrop of dismal conditions in Indian education, a mint new report authored by LoEstro Advisors, a Hyderabad-based education focused investment banking and consulting firm, says that a positive sea change is manifesting in private K-12 education countrywide writes Dilip Thakore

Seven decades after under the inspiring leadership of Mahatma Gandhi the country won its freedom from oppressive foreign rule, strong winds of change are blowing over post-independence India’s moribund education sector. Especially after the belated liberalisation and deregulation of industry in 1991 and after EducationWorld was launched in 1999 with the avowed mission to “build the pressure of public opinion to make education the #1 item on the national agenda”.

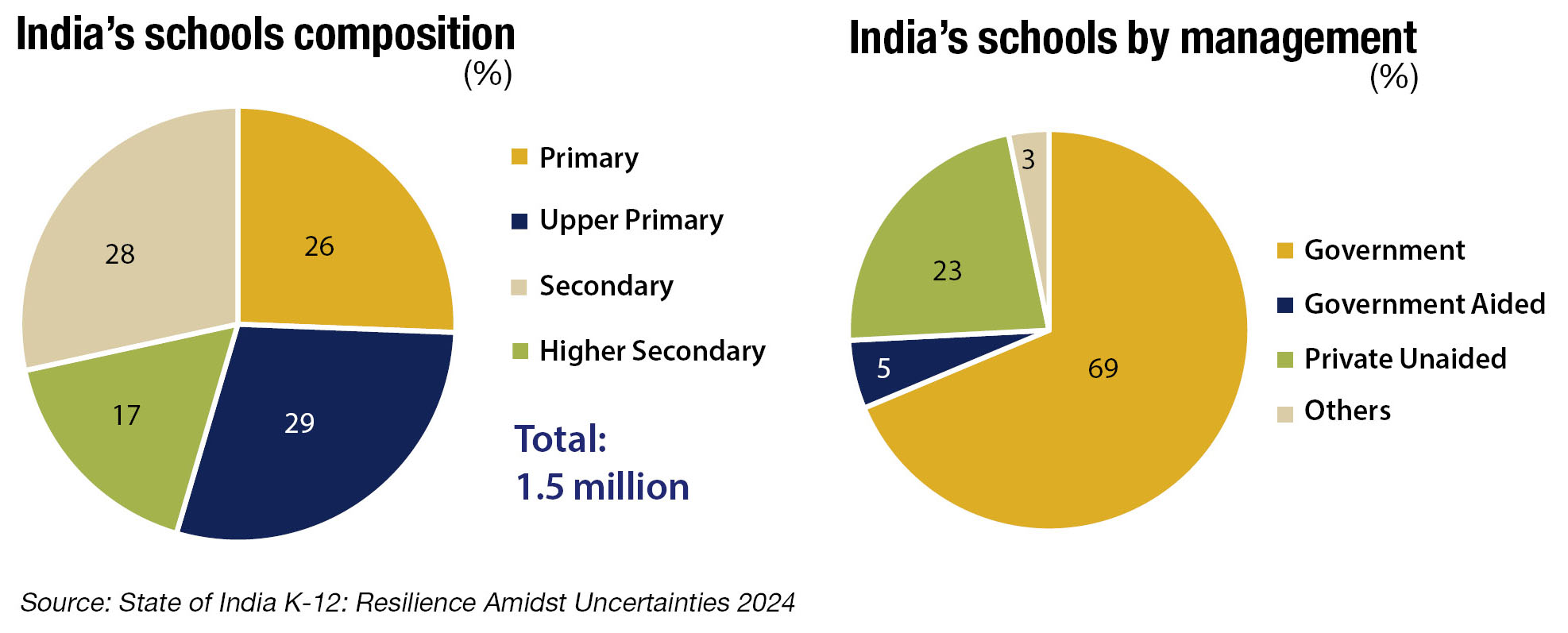

New awareness has dawned that resuscitating and upgrading the country’s 1.7 million pre-primaries, 1.50 million primary-secondary schools, 45,473 colleges and 1,168 universities is the essential precondition of 21st century India harvesting its demographic dividend — 700 million citizens are aged below 30 — and attaining the status of a middle class nation.

First, the back story of open, continuous and uninterrupted neglect of Indian education is necessary. In the first flush of freedom against the advice of Mahatma Gandhi and Sardar Patel, under the guidance of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was enamoured with the communist Soviet Union, independent India adopted inorganic socialism as its official ideology.

But although communist/socialist Soviet Union (now Russia) and the communist People’s Republic of China accorded high priority to the State providing universal high quality primary education, for various reasons (canalisation of national savings into capital-intensive white elephant public sector enterprises; neglect of agriculture, binding tax revenue-generating private sector enterprises in red tape) public education was under-funded ab initio. In 1967, a high-powered Kothari Commission strongly recommended investment of 6 percent of annual GDP (Centre plus states) in public education. That recommendation has remained on the back burner with national expenditure averaging 3.5 percent of GDP for over seven decades.

Moreover with 40 percent of meagre budget outlays of the Central and state governments allocated for over-subsidised higher education, the government school system has all but collapsed, especially in rural India which even seven decades after independence still grudgingly hosts 60 percent of the country’s 1.40 billion population. According to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) of the Pratham Education Foundation (estb.1994), over 50 percent of (neglected and recklessly promoted) class VII children in rural India can’t read class II textbooks and solve simple three by one digit division sums.

Pratham has been highlighting the growing illiteracy of rural India for over 25 years, to no avail. In the Union Budget 2024-25 presented to Parliament on February 1, the Central government’s allocation for public education was Rs.1.2 lakh crore, equivalent to 0.4 percent of GDP. The national outlay (after the allocations of 29 state governments and seven Union territories are added) has reportedly crept up to 4 percent of GDP.

The damage of continuous under-funding of public education has been augmented by low quality teaching-learning in India’s 1.20 million mainly state government schools. Twenty-five percent of over-paid government school teachers in rural India are absent daily, i.e, 1.25 million, and government schools are infamous for crumbling buildings, absence of libraries, laboratories and lavatories and multigrade teaching in furniture-less classrooms. Vocational and life skills education are unknown and there’s widespread aversion to teaching English/Inglish, India’s link language and language of the courts, business and industry. Therefore, most rural school-leavers either go back to their small farms to scratch out a living or join the ranks of the country’s estimated 140 million migrant labour ready and willing to travel anywhere to toil for pitiful wages.

Unsurprisingly, India’s estimated 55,000 private preschools and 450,000 private aided (teachers’ salaries paid by state governments) and independent (‘unaided’) K-12 schools, which nurture 48 percent of the country’s 260 million in-school children, provide superior quality education. But it’s pertinent to note that 400,000 of them are budget private schools (BPS) levying tuition fees of Rs.100-2,000 per month for providing primary-secondary education mainly to children from lower middle and working class households. Usually under-capitalised mom and pop enterprises, they can’t offer more than basic infrastructure and don’t pay teachers well enough to attract high quality faculty, with the result that children’s learning outcomes tend to be poor. Even so, because they claim to offer English-medium instruction, low-income parents beg, borrow and incur debt to enrol their children in neighbourhood BPS.

The total number of aided and unaided private primary-secondary schools providing acceptable quality education countrywide is estimated at a mere 50,000, of whom the 4,000 best are assessed in the annual EducationWorld India School Rankings — the world’s largest schools ranking survey.

The total number of aided and unaided private primary-secondary schools providing acceptable quality education countrywide is estimated at a mere 50,000, of whom the 4,000 best are assessed in the annual EducationWorld India School Rankings — the world’s largest schools ranking survey.

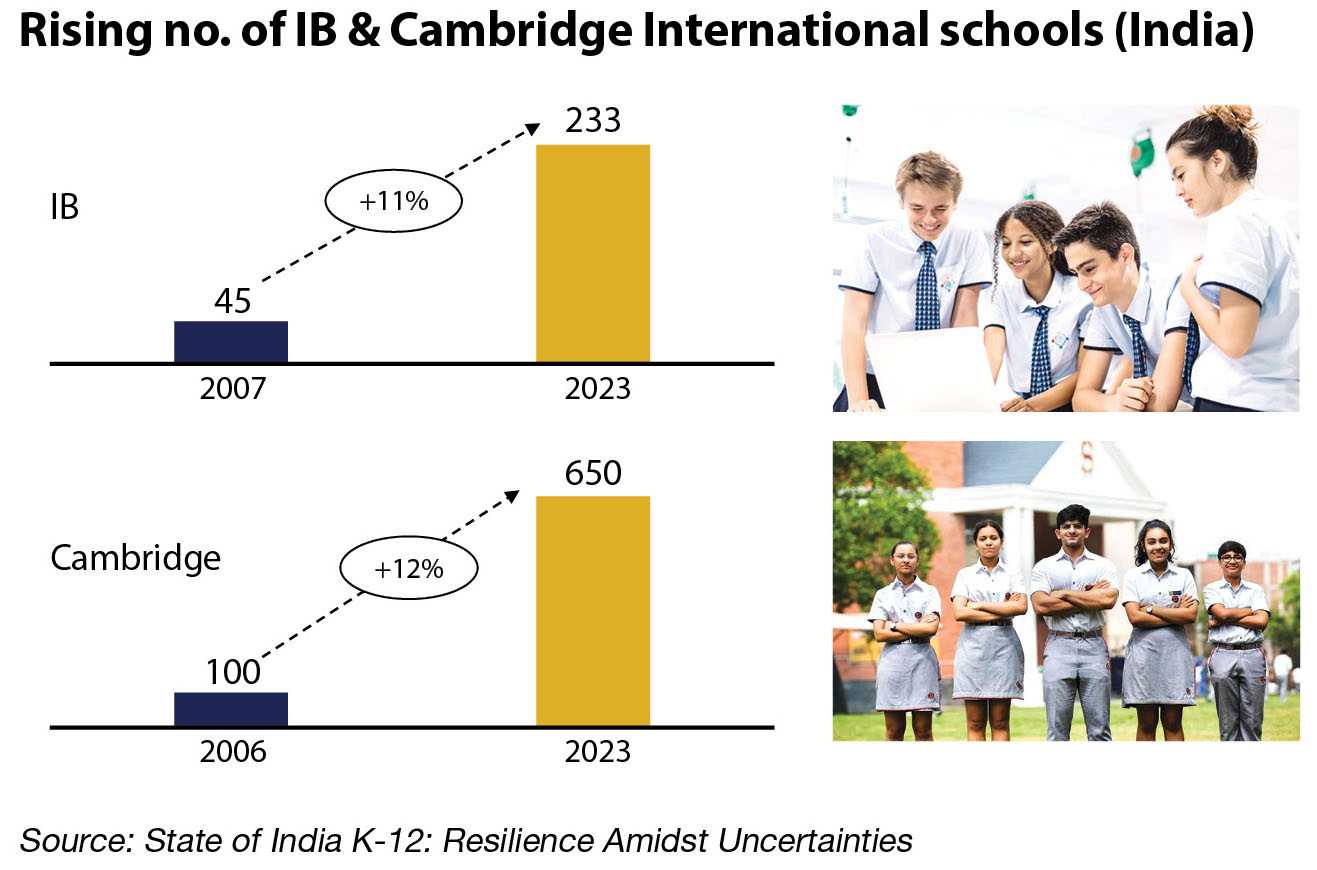

Yet although a few dozen of India’s top-ranked private schools affiliated with offshore examination boards such as International Baccalaureate (Geneva), Cambridge International (UK) and Advance Placements (USA) provide globally benchmarked K-12 education, the great majority of the country’s best private schools suffer in comparison with government and private schools in developed OECD and Asia-Pacific countries.

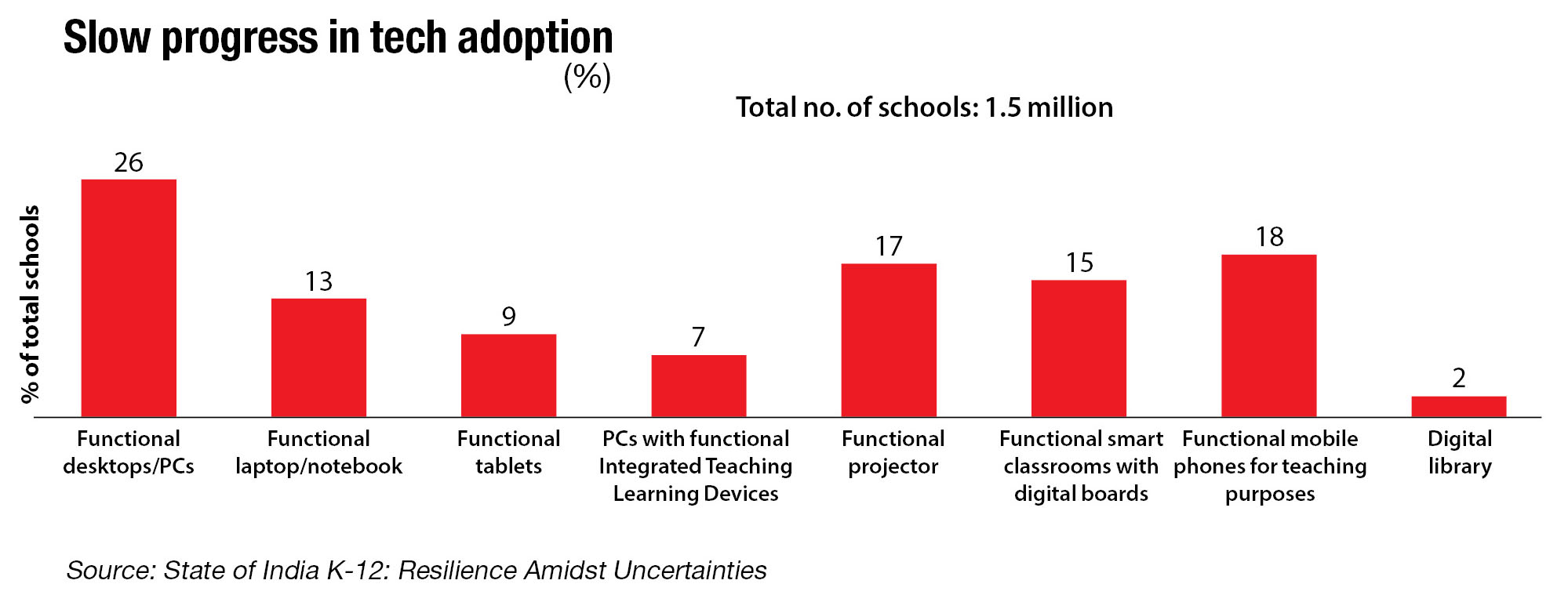

Knowledgeable monitors of Indian education concede that India’s school and higher education systems, with a few notable exceptions, are characterised by obsolete rote-learning pedagogies and assessment systems and technology aversion. The reluctance of India’s establishment, academy, educationists and educators to switch to latter-day syllabuses, contemporary pedagogies and technologies that develop the critical thinking, problem-solving, innovative and problems-solving capabilities of school and tertiary students is the prime factor behind poor productivity in government, industry and agriculture.

Against the backdrop of this dismal condition of Indian education, a mint new report titled State of India K-12: Resilience Amidst Uncertainties authored by LoEstro Advisors LLP (estb.2019), a Hyderabad-based education-focused investment banking and consultancy firm, says that a positive sea change in pedagogies and curriculums, accelerated tech adoption and professional development is manifesting in private K-12 education countrywide.

Government school teachers: negligent high-wage island

Although communists, socialists and left-liberals who dominate academia tend to deplore the growth and expansion of private schools and higher education institutions because they are “commercial” fees-levying enterprises, these arm-chair critics of private education have done precious little to raise public education standards while deriving profitable livelihoods from government-funded HEIs. Despite this, the salaries and remuneration of government school teachers determined by official Pay Commissions which decree the remuneration of 4 million pampered Central government servants, have continued to rise to the extent that their remuneration tends to be 10-12 multiples of BPS (budget private school) teachers. Consequently, they have emerged as a high wage island of the economy, notwithstanding their abysmal record of teacher truancy and rock-bottom learning outcomes of their pupils.

Therefore, reform and upgradation initiatives in early childhood care and education (ECCE) and K-12 education tend to be led by the country’s private schools — especially the best 4,000-5,000 primary-secondaries ranked in the annual EWISR league tables. Hence the critical importance of the comprehensive and well-researched LoEstro State of India K-12 report.

Gupta: new dynamism

“After prolonged hibernation, India’s K-12 education sector is experiencing dynamic change. The shutdown of schools for almost two years during the Covid-19 pandemic-forced curriculum upgradation and introduction of new technologies in school education. Simultaneously, government regulations and supervision have eased and NEP 2020 has standardised and rationalised school education by incorporating foundational ECCE into the K-12 system, and inflow of domestic and foreign investment of significant proportions into primary-secondary education has begun. Our report has been written to enable all stakeholders in education — parents, educators and government — to understand the new dynamism within K-12 education to enable them to ride the change,” says Rakesh Gupta, the highly qualified — IIT-Kharagpur, Indian School of Business, Hyderabad, former head of finance and strategy at People Combine Educational Initiatives (2011-2015) and management consultant with McKinsey & Co (India) — and lead author of the 80-page State of India K-12: Resilience Amidst Uncertainties report.

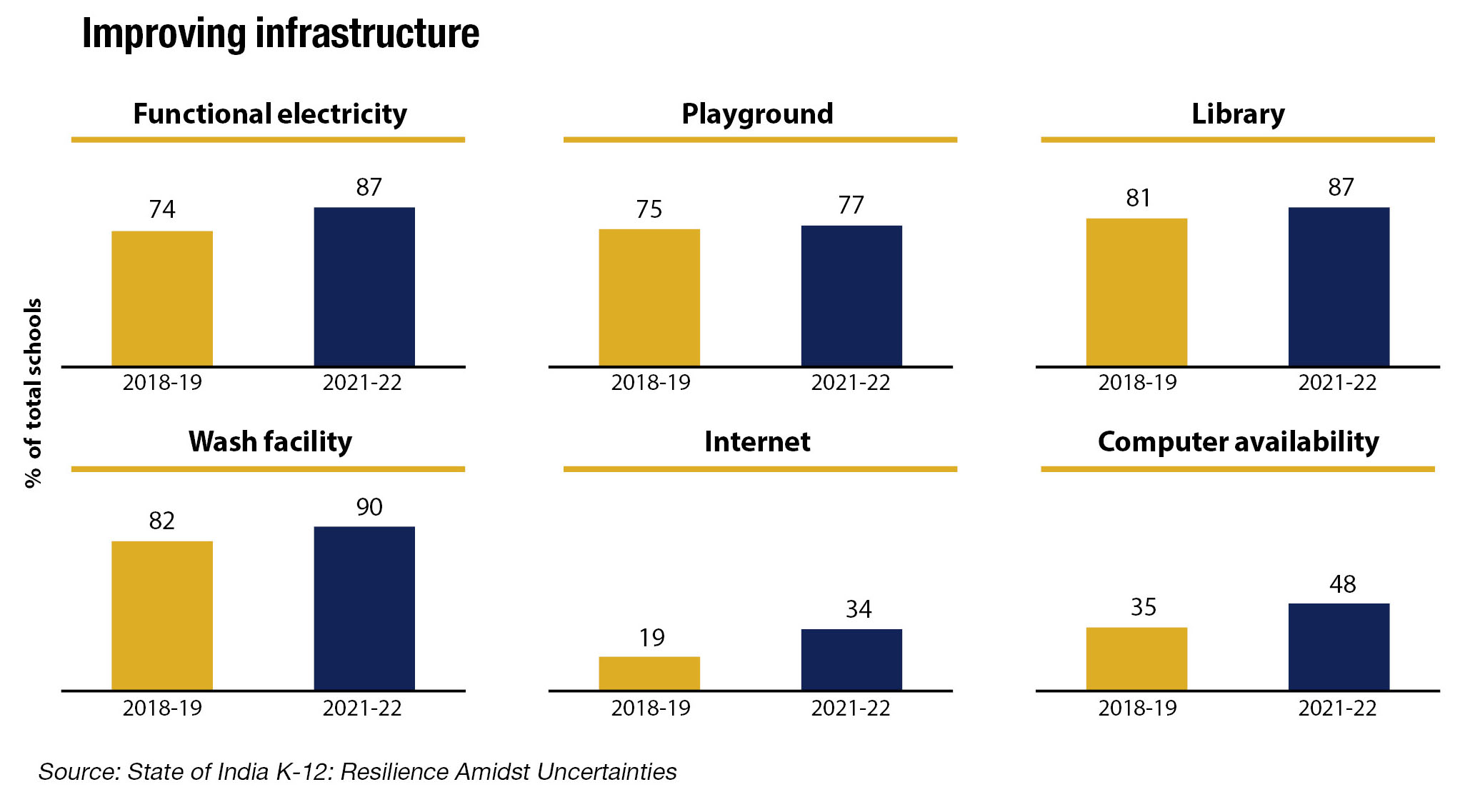

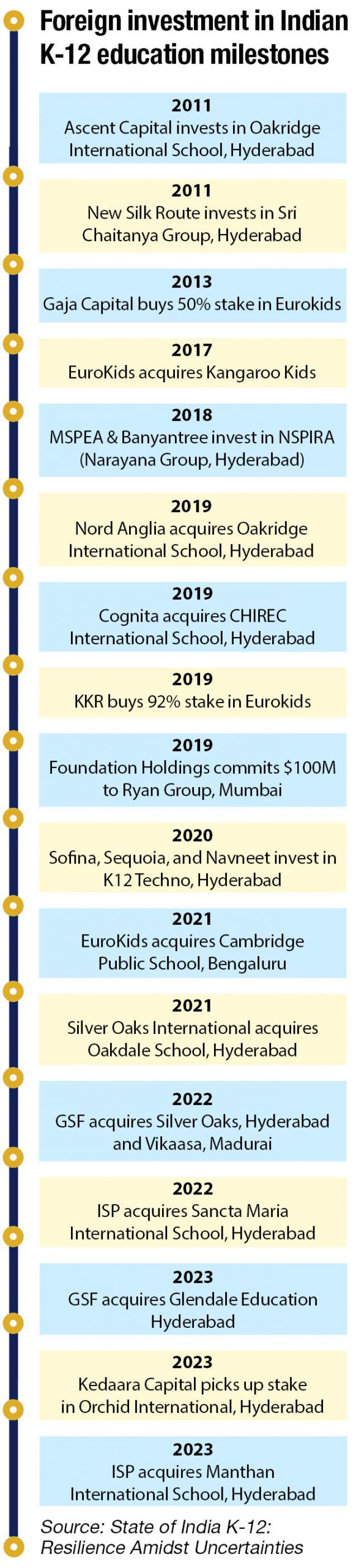

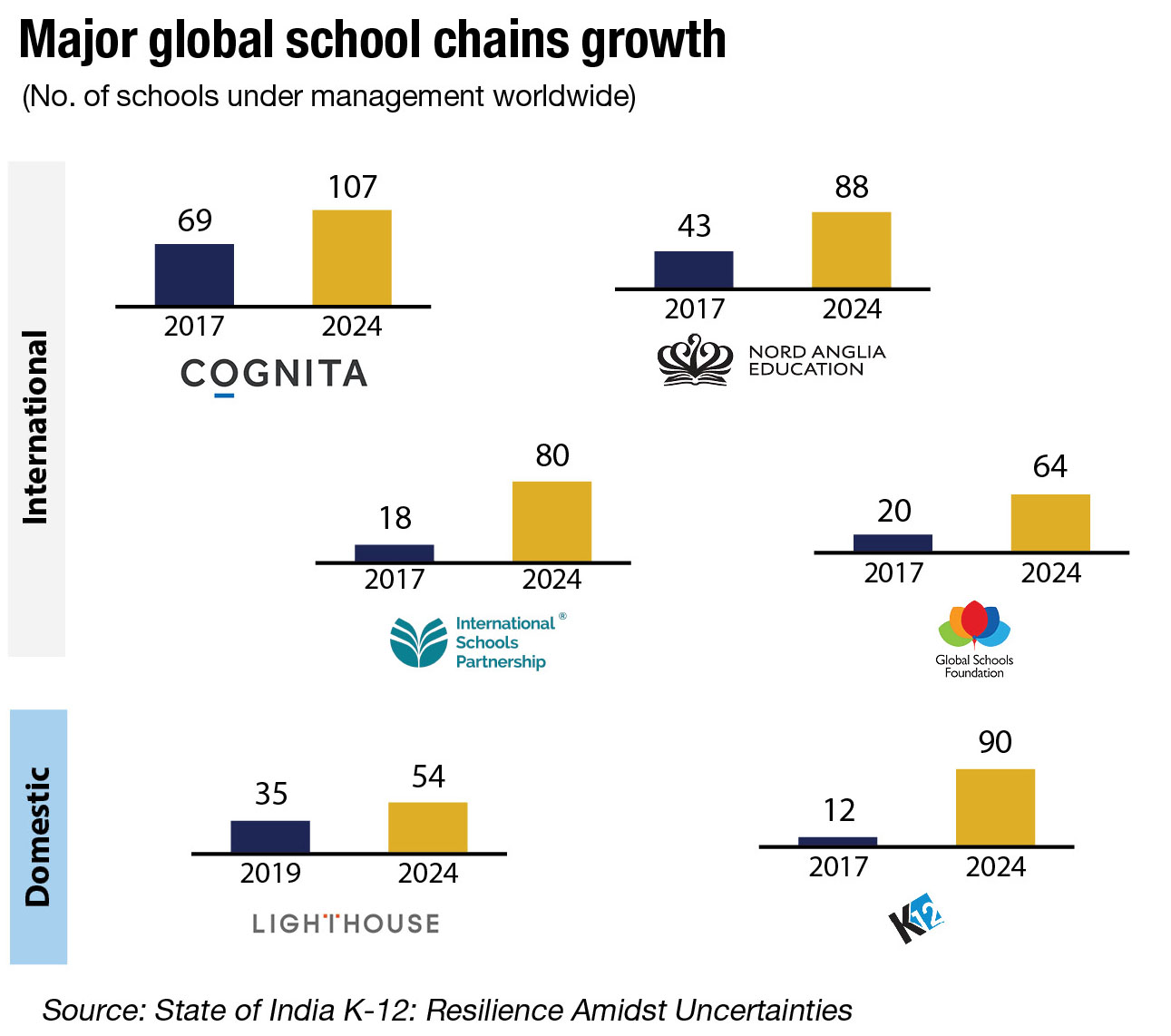

According to the report, led by private sector schools, education in the world’s second largest K-12 system is poised to experience positive sea change. GER (gross enrolment ratio) in primary, upper primary, secondary and higher secondary schools has shown steady improvement since 2018; dropouts have decreased; gender parity is 100 percent; school infrastructure and facilities have improved countrywide; national teacher-pupil ratio has improved and there is increasing interest and capital flow into private schools from strategic investors and venture capital firms since the beginning of the new millennium.

The downside of this rosy picture is: “several limitations” in curriculum and pedagogy (persistence with rote learning, compartmentalised curriculums, no change in assessment practices, limited focus on vocational and life skills learning and “challenges” in teacher training and capacity building) and inadequate adoption of education technology.“Our report highlights that it’s very important for all stakeholders to become bullish about introducing and disseminating technology in school education because it improves access, boosts learning outcomes and reduces costs. Moreover, changes in pedagogy — introduction of experiential, project-oriented learning, vocational and life skills and SEL (social and emotional learning) education — have become necessary. The report also flags the importance of greater investment in capacity building for teacher training and development and highlights greater capital inflows into K-12 education that will facilitate the introduction of technology and best international practices,” adds Gupta.

Dhankar: cultural pollution apprehension

LoEstro’s report on positive developments in private sector K-12 education, especially the increasing number of schools affiliating with the offshore Cambridge and IB boards and inflow of foreign capital into K-12 education (see pg. 45 and 46 tables), is likely to be the proverbial red rag to leftists and fellow-travelling liberal academics who are adamantly opposed to internationalisation of Indian education.

This tribe seems wholly unaware of a steady exodus from government schools and low-income households desperate to enroll their children in private schools, often resort to selling property and incurring debilitating household debt. Although bottom-of-pyramid households in rural India often don’t have the choice to enroll their children in private schools, in urban India, cooks, drivers, housemaids and even migrant labour make huge financial sacrifices to enroll their children in private schools.

The steadily increasing number of primary-secondary schools affiliating with foreign examination boards and rising foreign investment flow into K-12 education doesn’t sit well with Dr. Rohit Dhankar, former professor of education at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru (estb.2010), ranked India’s #1 private university for social sciences in the latest EW India Higher Education Rankings 2024-25.

“The philosophical outlook of Sri Aurobindo and Rabindranath Tagore taught us that a strong sense of identity and self-respect is best developed within one’s regional and/or national culture through firm ties with family and local community. This means that children should develop strong cultural roots before they start flying. Therefore, internationalisation synonymous with the import of Western cultural norms and value premises into school education — higher education could be an exception because older children tend to be more mature — is not in the national interest. The same argument applies to foreign investment into K-12 education. The national interest would be better served if a determined effort is made to upgrade our own indigenous education systems, with special focus on rigorous training and professional development of teachers. NEP 2020 pays considerable lip service to developing Indian knowledge systems, but this aspiration is contradicted by inviting foreign examination boards and foreign investment into K-12 education,” says Dhankar, founder-secretary of Digantar, a Jaipur-based education NGO.

IB-affiliated Harrow International School, Bengaluru students

On the other hand, Dr. A.S. Seetharamu, former professor of education at ISEC (Institute for Social and Economic Change), Bengaluru, (estb.1972) and currently a Bengaluru-based education consultant, welcomes progressive globalisation and adoption of global best practices in private K-12 education which he believes will filter into BPS and government schools.“With the steady growth and expansion of India’s middle class, demand for high quality pre-primary and K-12 education is becoming pressing. Increasingly, middle class parents and youth are demanding internationally benchmarked education that prepares them for well-paid employment in India and abroad. This demand has generated supply from foreign examination boards and foreign investors. This is a positive development because it will raise teaching standards and learning outcomes in K-12 education. The plain truth as evidenced by the poor performance of our children in international tests such as PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) and the low ranks awarded to India’s best universities by the London-based rating agencies, QS and Times Higher Education, is that our schools and universities lag behind Western and Asian education institutions in terms of learning outcomes, research and innovation. Therefore, internationalisation of K-12 education is a welcome development,” says Prof. Seethramu.

Seetharamu: welcome development

Dr. Seetharamu doesn’t share Prof. Dhankar’s apprehension of academic and cultural pollution. “Indian civilisation and Hinduism have survived military invasions and cultural impositions for thousands of years starting from the time of Mahmud of Ghazni to the rule of the British Empire. That’s because our cultures live in homes rather than formal institutions. India’s syncretic civilisation is essentially tolerant and secular. It absorbs the best practices of all creeds and civilisations and becomes stronger. This will also be the outcome of internationalisation of Indian education,” he prophesies.

Optimism about favourable developments in foundational K-12 education and its incremental internationalisation is shared by bona fide educationists, even though it might mean more intensive competition within this sector. Praveen Raju, co-chairman of the Delhi-based ARISE (Alliance for Re-Imagining School Education), a lobby of promoters and managers of upscale independent schools, “eminent educators, foundations, civil society representatives, think tanks and technical experts” that proposes policy reforms to the Central and state governments, welcomes internationalisation of K-12 education.

Optimism about favourable developments in foundational K-12 education and its incremental internationalisation is shared by bona fide educationists, even though it might mean more intensive competition within this sector. Praveen Raju, co-chairman of the Delhi-based ARISE (Alliance for Re-Imagining School Education), a lobby of promoters and managers of upscale independent schools, “eminent educators, foundations, civil society representatives, think tanks and technical experts” that proposes policy reforms to the Central and state governments, welcomes internationalisation of K-12 education.

Raju: accelerated internationalisation

“This is a positive development. Growth and expansion of the Indian middle class and integration of the Indian economy with the global economy has spiralled the demand for internationally comparable K-12 education. This will intensify competition among the top-ranked schools and compel them to raise teaching-learning standards and adopt global best practices. In turn, this will force examination boards in India to review their assessment systems which will compel pedagogy and curriculum changes in affiliated schools. For instance, CBSE — India’s largest national school-leaving examinations board — has already introduced wide-ranging assessment reforms to lead children away from rote learning towards developing critical thinking and analysis skills. It’s high time our school education system aligns with the rest of the world. Internationalisation of India’s hitherto insulated K-12 education system will accelerate this process,” says Raju, an alum of Osmania University and promoter-director of the Suchitra Academy, Hyderabad, ranked the pearls city’s #3 co-ed day school in the EW India School Rankings 2023-24.

It is pertinent to bear in mind that although the State of India K-12 purports to report the condition of K-12 education in India, its prime focus is on private primary-secondary education. This is inevitable since LoEstro is a private sector for-profit investment banking and consultancy firm engaged in providing equity finance, mergers and acquisitions, and structured finance services to education institutions and aspiring and extant promoters in K-12 education. Therefore although in its initial pages, the report provides a holistic perspective of India’s K-12 system — number of schools, teachers countrywide — the main focus and interest of State of K-12: Resilience Amidst Uncertainties is to provide a roadmap for existing and aspiring entrepreneurs to grow and enter K-12 education in India for profit, philanthropy or a mix of both. Most of the advice dispensed by the report is irrelevant and/or inapplicable to government schools.

It is pertinent to bear in mind that although the State of India K-12 purports to report the condition of K-12 education in India, its prime focus is on private primary-secondary education. This is inevitable since LoEstro is a private sector for-profit investment banking and consultancy firm engaged in providing equity finance, mergers and acquisitions, and structured finance services to education institutions and aspiring and extant promoters in K-12 education. Therefore although in its initial pages, the report provides a holistic perspective of India’s K-12 system — number of schools, teachers countrywide — the main focus and interest of State of K-12: Resilience Amidst Uncertainties is to provide a roadmap for existing and aspiring entrepreneurs to grow and enter K-12 education in India for profit, philanthropy or a mix of both. Most of the advice dispensed by the report is irrelevant and/or inapplicable to government schools.

The authors of the report seem unmindful that a widening gap between private and public education is likely to invite ideologically-driven restrictions on the growth and development of private schools by way of tuition fees regulation, government imposed admission quotas, expat faculty recruitment, teachers’ remuneration ceilings etc to discourage foreign investment and capital.

The authors of the report seem unmindful that a widening gap between private and public education is likely to invite ideologically-driven restrictions on the growth and development of private schools by way of tuition fees regulation, government imposed admission quotas, expat faculty recruitment, teachers’ remuneration ceilings etc to discourage foreign investment and capital.

Logically, the entry of foreign examination boards and foreign capital into private education should prompt government to raise teaching-learning standards in the country’s 1.20 million public schools. Yet typical government response to competition in industry, business and education is protectionism that levels standards downward. Therefore, not a few monitors of Indian education apprehend a reversal of the liberalisation and deregulation of K-12 education.

However Payal Jain, partner at LoEstro Advisors, believes that such apprehension is unwarranted. “The investment flowing into India’s education sector is not hot money; it is patient capital driven by a combination of reasonable return on investment and philanthropy. The policy framework of the K-12 sector has been stable for the past 12-15 years with the Supreme and several high courts having upheld the right of investors in education to reasonable return on investment. There is growing awareness within government and society that inflow of private equity into education enables investment in teacher and curriculum development. This will also open global opportunities for teachers and students exchanges and raise teaching-learning standards across the board. Therefore, the process of liberalisation of education is likely to accelerate in the near future,” says Jain, an alumna of the top-ranked Shri Ram College of Commerce, Delhi and IIM-Indore, who came aboard LoEstro in 2020 after three years with Goldman Sachs, Delhi (2017-20) and was appointed partner last year.

Payal Jain

Self-evidently, the national interest demands that the logic of the historic industry and business liberalisation and deregulation initiative of 1991 is applied in Indian education. That initiative which ended over half a century of pernicious licence-permit-quota raj which cabined, cribbed and confined private industry for over half a century, immediately doubled annual GDP growth rates and lifted an estimated 400 million citizens out of deep poverty. Reform and upgradation of teaching-learning standards in K-12 education that is manifesting in private schools is seeping into Central government-run Kendriya Vidyalayas and Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas, and latterly into state government schools, notably of the Delhi state government.

Therefore the refreshing LoEstro report predicts acceleration of this process in the near future. The company’s crystal ball presents an optimistic scenario for all stakeholders in primary-secondary education. For parents and students, it prophesies hybrid schools delivering multimodal education, personalisation of education and projects-based pedagogy. For school managements, it predicts relaxation of government regulations, innovative business models, investment in professional development, partnerships for marketing and branding, and technology access. For patient capital investors, it envisages conducive financial instruments and structures. And to regulators, LoEstro advises predictability and customisation of regulations, ease of operating schools, providing a conducive tech ecosystem and promoting private capital.

Therefore the refreshing LoEstro report predicts acceleration of this process in the near future. The company’s crystal ball presents an optimistic scenario for all stakeholders in primary-secondary education. For parents and students, it prophesies hybrid schools delivering multimodal education, personalisation of education and projects-based pedagogy. For school managements, it predicts relaxation of government regulations, innovative business models, investment in professional development, partnerships for marketing and branding, and technology access. For patient capital investors, it envisages conducive financial instruments and structures. And to regulators, LoEstro advises predictability and customisation of regulations, ease of operating schools, providing a conducive tech ecosystem and promoting private capital.

What the mildly worded State of India K-12: Resilience Amidst Uncertainties doesn’t say is that enabling these predictions and recommendations is a necessary precondition for realising the Viksit Bharat and $3 trillion GDP goals by 2047 when the country will celebrate a century of freedom from foreign rule.

Also read: The hidden potential of the Indian education system

Add comment