Tamil Nadu: SEP over-kill

Shivani Chaturvedi (Chennai)

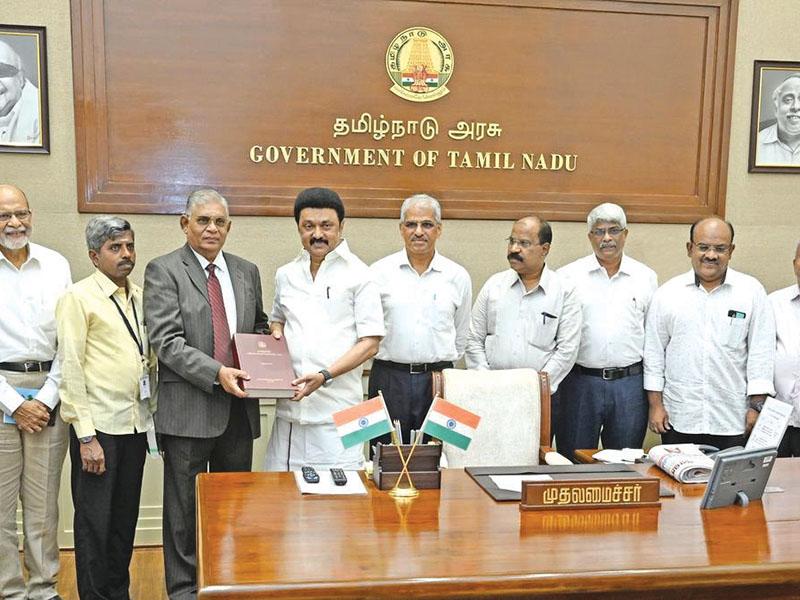

A draft of Tamil Nadu’s state Education Policy (SEP), developed as an alternative to the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, has been submitted to the ruling DMK government by the Justice Murugesan-led panel.

After the DMK was voted to power in the legislative assembly election of 2021, while presenting the new government’s budget for 2022, Chief Minister M.K. Stalin announced that an exclusive education policy for Tamil Nadu would be formalised. In June 2022, he established a committee of experts from various fields, chaired by Justice (Retd.) D. Murugesan, to formulate the SEP. On July 1, the Murugesan Committee submitted a 550-page report in English and a 600-page report in Tamil, to the chief minister.

Major recommendations include that the state government takes appropriate measures to ensure that ‘Education’ is brought back to List II (the states list) of the Constitution; that Tamil language should be the medium of instruction in anganwadis (mother-child care centres) and child development centres; Tamil is the first language of education right from primary school to university level; continuation of Tamil Nadu’s dual-language policy of promoting English and Tamil, and abolition of public examinations for classes III, V and VIII.

Moreover, the Murugesan Committee has proposed that the admission age into class I in Tamil Nadu’s 39,300 government and government-aided schools affiliated with the Tamil Nadu Board of Secondary Examinations (TNBSE) and nearly 5,000 Matriculation Board schools should be five years. This despite the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, prescribing the entry age for class I as six.

The Justice Murugesan Committee’s recommendations for the proposed SEP has ignited a lively debate in academia about its provisions, and whether an SEP at variance with NEP 2020 is in the larger interest of children in the state (pop.84 million).

“If Tamil is introduced as the medium of instruction through school all the way to university, it will surely enable students from rural backgrounds. However, if the DMK government wants education to be brought back in the States list, it should ensure that the education system won’t be diluted. It should ensure teaching-learning quality in the state is on a par with national standards,” says K. Palanivelu, a Chennai-based educationist and former director of the Centre for Climate Change and Adaptation Research at Anna University.

This problem of standardisation necessary to enable mobility of students and later professionals, from Tamil Nadu to other states and abroad, worries other knowledgeable educationists as well. “As many as 72 competitive examinations are held every year across the country including IIT-JEE and NEET. If all states follow NEP 2020, there will be standardisation of syllabi and perhaps learning outcomes. This is especially important for maths and science. Moreover, the Murugesan Committee has recommended the primacy of Tamil as the medium of instruction. But the previous DMK government had decreed this 16 years ago. Yet the middle class paid no attention. It continues to send its children to private English-medium schools. Parents’ choice of medium of instruction was pointedly endorsed by the Supreme Court in 2014. The apex court held that parents are the best judge of the language in which their children should study. This is the best solution. The DMK leadership should stop practising Tamil Nadu exceptionalism and beating the Tamil drum. Indeed it is doing Tamil-medium students a disservice as they won’t be able to find employment outside Tamil Nadu and perhaps not even in managerial positions within Tamil Nadu,” warns educationist Dr. S. Somasundaram.

Academics in Chennai are almost unanimous that the new three-year-old DMK government’s opposition to NEP 2020 and determination to introduce its own SEP is rooted in the party’s antagonism toward “Hindi imperialism,” i.e, imposition of Hindi — the lingua franca of the so-called BIMARU (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) states — as the national language. In the south, these states are widely perceived as the country’s most socio-economically backward and poorest, although most populous. In 1960 when Hindi was officially declared the national language, there was widespread rioting in the southern states with Tamil Nadu threatening secession from India.

As a result, this declaration was rolled back and English was retained as the ‘associate’ national language and remains the language of the upper judiciary, business and the inter-state link language of the country. Significantly – and myopically – NEP 2020 reiterates the three language formula, making learning of Hindi compulsory for children countrywide. A major demand of the DMK — and indeed of all political parties in Tamil Nadu — is the dual language learning and usage policy under which only Tamil and English are taught in government schools and used in state administration. This demand has been dutifully endorsed by the Justice Murugesan Committee.

However, the consensus among academics in Chennai is that acceptance of this and other recommendations of the Murugesan Committee does not require legislation of a separate State Education Policy. “A separate SEP is an overkill. The interest of Tamil Nadu’s children will be best served if their education is in sync with the rest of the country,” says Somasundaram.

Good advice.

Add comment