No products in the cart.

Union Budget 2025-26: Half prescription for Viksit Bharat

Constructing enabling infrastructure is a necessary but not sufficient condition of GDP growth. There’s little awareness in the budget that hard infrastructure requires to be maintained and managed by soft infrastructure — well-educated and trained human resources to optimise return on investment – Dilip Thakore

Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman & team: hard and soft infrastructure dichotomy

Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s eighth consecutive budget 2025-26 was presented to Parliament and the nation only four weeks ago at time of writing, but it seems to have been totally forgotten. Because it trod a safe, well-trodden path without any notable breakthrough proposals. To the finance minister’s credit, the major thrust continues to be on capital expenditure for infrastructure development which has huge multiplier effect, and fiscal rectitude, i.e, continued reduction of the fiscal deficit necessary to contain inflation, a hidden tax that bears down most heavily on poorest and most vulnerable citizens.

Therefore, capital expenditure on infrastructure which suffered a 12 percent shortfall at Rs.13.18 lakh crore as indicated by the revised expenditure in 2024-25 cf. the budgeted Rs.15.01 lakh crore, has been restored to Rs.15.48 lakh crore. This provision of almost 31 percent of the total budgeted expenditure in 2025-26, is commendable because investment in roads, highways, ports, power and railways enable citizens to conduct their businesses with greater ease and contribute to GDP and national wealth growth. Infrastructure spending is a far better option to help the public than handing out freebies and grants to EWS (economically weaker sections) as is the latest fashion of the Centre and state governments. Infrastructure development smooths the way for people to fend for themselves rather than rely on government handouts and largesse. The BJP/NDA government at the Centre deserves encomiums for persistently allocating 30 percent of its annual expenditure — even during the Covid pandemic years — to infrastructure development.

This strategy — and “taking the capitalist road” — the open secret of neighbouring China’s astonishing compounded double digit GDP growth for over 20 years (1978-2008), explains India’s quick bounce back to 6 percent-plus yearly GDP growth in the post-Covid era. Yet it’s important for government and the public to bear in mind that infrastructure provision is a necessary but not sufficient condition of GDP growth. Roads, bridges, power stations and railway tracks also need to be carefully maintained, a national failing, but for which our annual economic growth rate would be higher and nearer to the 8 percent per year required to attain the Prime Minister’s Viksit Bharat and $30 trillion GDP (cf. $4 trillion currently) goals set for 2047, when India will celebrate its centenary of freedom from foreign rule. Within the establishment and Indian society, there’s little regret or shame that the annual GDP of neighbouring China has risen to $18 trillion whereas ours is a mere $4 trillion. Or that in 1950, their GDP was less than ours right until 1978, after which they have left India lagging way behind in the global development race.

The BJP/NDA government also needs to be commended for its determined effort to continuously reduce the nation’s fiscal deficit which has fallen continuously year after year from the high point of 9.2 percent of GDP in 2020-21 (the Covid high noon) to 5.6 percent in 2023-24 to 4.8 percent last year and is budgeted to decline to 4.4 percent of GDP in 2025-26. This, despite pressure from industry to ease credit to boost GDP which is expected to grow to Rs.356.97 lakh crore ($4 trillion) in nominal terms (unadjusted for inflation) in 2025-26.

Balancing the budget by reducing the fiscal deficit is important because the fiscal deficit amount (budgeted at Rs.15.68 lakh crore in 2025-26) necessitates printing additional money pumped into the economy without commensurate output, resulting in too much money chasing too few goods driving up prices, i.e, inflation. Therefore, the Fiscal Responsibility & Budget Management Act, 2003 mandates the Central and state governments to “endeavour to ensure” that the fiscal deficit does not exceed 3 percent of GDP.

The third highlight of Budget 2025-26 is a substantial income tax concession that Finance Minister Sitharaman has conferred upon India’s expanding middle class which “provides the strength for India’s growth”. Under the revised income tax payable structure, individuals with annual income of a substantial Rs.12.75 lakh per year are henceforward exempt from paying income tax (after availing Rs.75,000 standard deduction) and out of the direct taxes net. But for this higher exemption threshold, they would have been obliged to pay Rs.65,000 to the Central government.

By Indian yardsticks this is a substantial concession amplified by lesser percentage of income payable on higher slabs. India’s middle class whose number is estimated at 430 million is indeed stoking the engines — even if sub-optimally — of national growth and is most vocal in expressing dissatisfaction with inadequate urban infrastructure and rising inflation. Therefore this year’s budget has substantially smoothed the feathers of this flock which is increasingly voting with its feet to exit the country, given opportunity. Belatedly there is rising awareness within the somnolent establishment of the need to stem this continuous brain drain. Hence the infrastructure development, inflation management and direct tax reduction thrust of this essentially middle class budget.

Yet while the strategy of Budget 2025-26 to invest in modern infrastructure for its downstream multiplier impact, inflation management to ameliorate the burden of the poor and rewarding the middle class is intelligent, one wonders why successive governments at the Centre and in the states advised and enabled by a pantheon of eminent economists and development scientists, persist in making a distinction between hard infrastructure — roads, bridges, power plants, railways — and soft infrastructure, i.e, human resources. Unfortunately since newly independent India, impoverished by almost 200 years of loot-and-scoot British rule embarked upon the path of national development and reconstruction, there’s been little awareness that hard infrastructure requires to be managed and maintained by well-educated and trained human resources to optimise return on investment.

Subramanian: contradictory sophistry

Although in the initial years after the newly independent nation ill-advisedly opted for adoption of the capital-intensive heavy industry development model (instead of the labour-intensive wage goods model), during the years of the Soviet-inspired First and Second Five year Plans (1951-61), GDP growth averaged 4 percent, during the next 20 years it plunged to 3.25-3.5. Primarily because the advice of a high-powered panel headed by Dr. D.C. Kothari, Chairman of University Grants Commission, to increase the annual national outlay for education to a minimum of 6 percent of GDP was ignored.

Post-independence India has paid a heavy price for ignoring this sage advice. Because of poor quality education, especially primary-secondary schooling, substantial investment in infrastructure and heavy industry, has not paid off because of substandard manpower. Agriculture yields per acre in India are one-tenth to one-fifth of developed OECD countries and even newly developed China, because as repeatedly testified by the Annual Status of Education Report of the Pratham Education Foundation, class VII children in rural India can’t read class II textbooks and solve simple numerical sums. With the large majority of farmers unable to comprehend simple fertiliser and pesticides usage leaflets, calculate farm input measures and understand elementary finance (let alone voluminous paperwork demanded by banks), it’s no wonder that farm productivity has remained rock-bottom despite substantial investment in roads, irrigation, electricity and market connectivity.

“Output increases the most in India with an increase in the quality of labour. The significance of education for economic growth has been widely acknowledged since Gary S. Becker’s groundbreaking research which earned him the Nobel Prize. In fact, the historical evaluation of high-growth episodes in Chapter 5 shows clearly that every country improved its educational outcomes to further its economic growth. Among all factor inputs including capital, quality and quantity of labour, energy, material and services, a 1 percent increase in labour quality makes the greatest contribution… As the quality of labour depends significantly on education, this underlines the importance of education for India to reap its demographic dividend,” writes Krishnamurthy Subramanian, former Chief Economic Advisor to the Government of India, professor at the top-ranked private sector Indian School of Business, Hyderabad and currently Executive Director of the International Monetary Fund, in his deeply researched and well-argued India@100 — Envisioning Tomorrow’s Economic Powerhouse (Rupa, 2024). For a review of this book see (https://www.educationworld.in/perfect-prescription/).

Yet when interviewed by your correspondent for EducationWorld, Subramanian defended the BJP/NDA government’s failure to enhance the outlay for education to 6 percent of GDP despite its election manifestos repeatedly promising to do so. Subramanian contended that since the GDP is rising by more than 6 percent annually, the outlay for education is rising automatically (https://www.educationworld.in/ew-interview-dr-krishnamurthy-subramanian-chief-economic-adviser-govt-of-india/).

Such sophistry is echoed by all establishment economists including V. Anantha Nageswaran (“inputs don’t guarantee outcomes”) and even independent journalist Swaminathan Aiyar who stresses that efficiency of expenditure rather than larger outlays, is required to improve public education.

In her 74-minute Union Budget 2025-26 presentation speech to Parliament and the nation, finance minister Sitharaman ringingly quoted Telugu poet and playwright Gujarada Appa Rao (1862-1915) to the effect that “A country is not just its soil; a country is its people” spotlighting agriculture, MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises) and investment in people, economy and innovation as the “theme” of her latest budget. All these sectors need high quality labour/people, ipso facto underscoring that education and skilling is the essential precondition of realising the theme of Budget 2025-26.

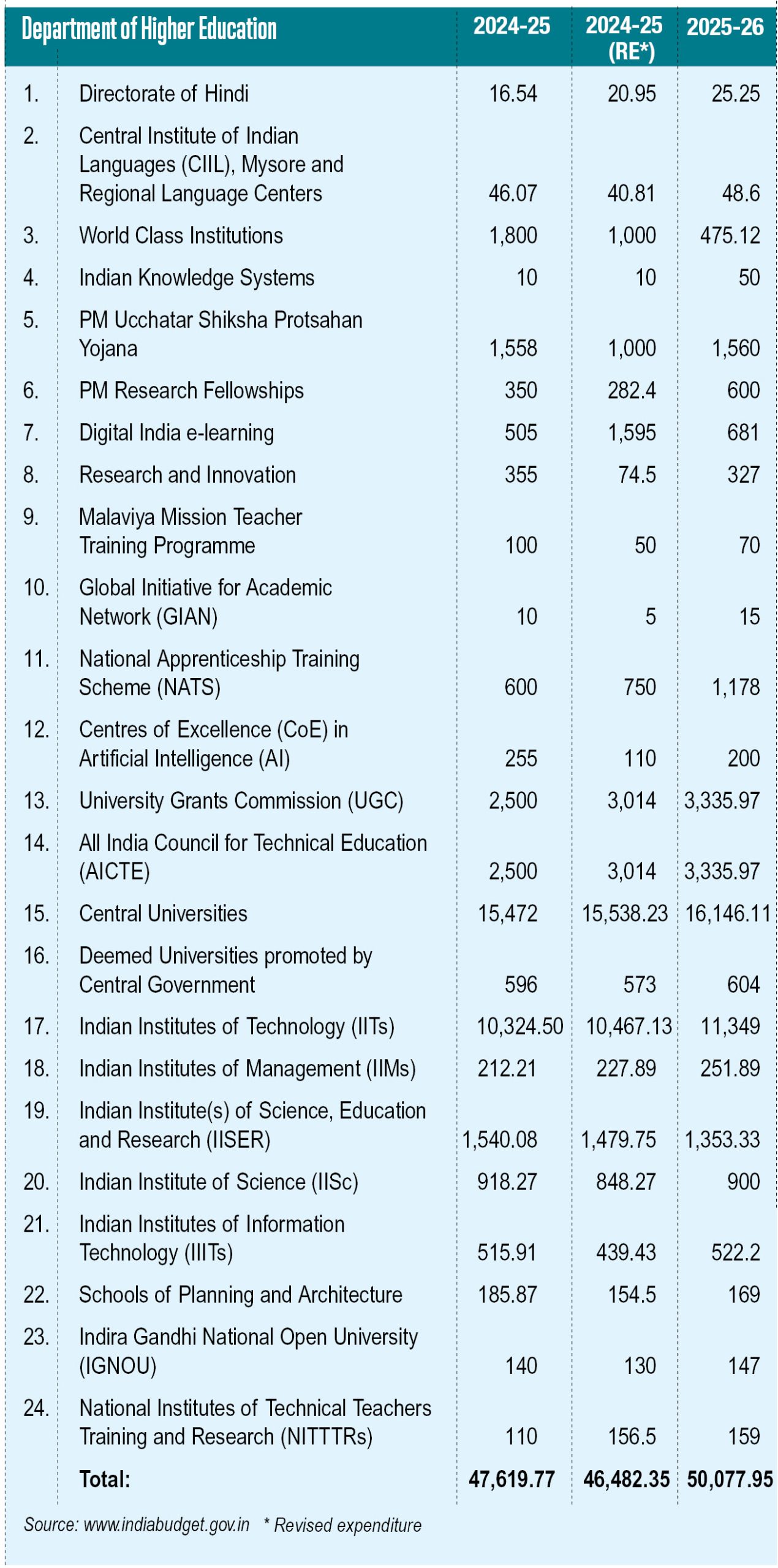

However, as usual eloquent rhetoric and fine sentiments haven’t been backed by meaningful allocations for education in Budget 2025-26. The Centre’s total outlay for education this year is budgeted at Rs.1.28 lakh crore cf. Rs.1.20 lakh crore last year and actual (revised) expenditure of Rs.1.14 lakh crore in 2024-25. In this connection, it’s pertinent to note that the social services (education and health) budget for 2025-26 at Rs.1.98 lakh crore is 17.5 percent lower than the Rs.2.40 lakh crore budgeted in 2024-25, against which the revised expenditure was Rs.1.88 lakh crore. Obviously to reduce the fiscal deficit of 2025-26, the social services outlay has been slashed. There is a big shadow between investment in people as proclaimed in the budget and putting money on the table for that purpose.

Rural government school: unacceptable infrastructure

Indeed after examining the static provision made in Budget 2025-26 for education, one wonders whether the finance minister is aware that India grudgingly hosts the world’s largest child and youth population aggregating 560 million. Setting quality issues aside for the moment, the scale of demand for basic infrastructure — classrooms, teachers, libraries, laboratories, digital connectivity etc — is massive. As the latest Unified District Information System for Education PLUS (UDISE+) 2023-24 of the Union education ministry released on December 30 testifies, even 75 years after independence there are unacceptable shortages of laboratories, lavatories, libraries and electricity in the country’s 1.47 million schools.

This deficiency combined with indifferent teaching, outdated syllabuses, textbooks and curriculums prompts 22 percent of enrolled children to drop out of primary schools, 36 percent out of secondary schools and 55 percent from higher secondary classes — waste of human resource of colossal scale.

Moreover, even children retained in school exhibit below par learning outcomes. For the past two decades, year after year, the Annual Status of Education Report which field tests primary and adolescent school children in rural India, has been reporting very poor reading and numeracy learning outcomes. For instance, the latest ASER 2024 released on January 30, says that 52 percent of rural children in class V can’t read class II textbooks, and 70 percent can’t solve simple division sums. That’s the all-India average. In some states including Telangana, Karnataka and Assam, over 70 percent of class V rural children can’t read class II textbooks.

Given this dismal grassroots reality, India’s education sector obviously needs massive investment and makeover. Despite this, the Central government’s annual allocation for education as a percentage of GDP has been steadily declining from 0.44 percent in 2023-24 to 0.37 percent in 2024-25 and 0.35 percent in 2025-26.

Apologists of the Congress party, which ruled India for 45-50 years after independence and is primarily responsible for the neglect of Indian education, as of the ruling BJP/NDA government which has failed to remedy this situation, argue that education — especially K-12 education — is mainly a state government subject. Therefore, India’s 29 state governments are to blame for the shambles of Indian education.

But it’s pertinent to bear in mind that most states were/are also ruled by the Congress or BJP/NDA. The blame for the poor learning outcomes of India’s children and youth has to be laid at the doors of benighted leaders of these (and other) political parties. Indeed post-independence India’s entire political class which was quick to seize “the commanding heights of the Indian economy”.

Against this backdrop of continuous failure to upgrade public education – an estimated 52 percent of India’s 260 million in-school children are in government schools — as in her previous seven budgets, the long-tenured Dr. Sitharaman has made a nominal budgetary increase for developing public education — from Rs.1.20 lakh crore in 2024-25 to Rs.1.28 lakh crore in 2025-26. Among the most prominent: an undisclosed amount for the country’s 1.6 million Anganwadi Centres (AWCs) which “provide nutritional support to more than 8 crore (80 million) children and 1 crore (10 million) pregnant women and lactating mothers all over the country” as also to 2 million “adolescent girls in aspirational districts in the north-east region”. For improving the nutrition of these children and women, the “cost norms” will be “enhanced appropriately”, said Sitharaman in her budget speech. Curiously AWCs served by a solitary under-paid ‘helper’ fall within the administrative purview of the Union Women & Child Development ministry which has made a nominal increase by allocating a paltry Rs.26,889 crore (cf. Rs.21,260 crore in 2024-25) for 80 million children in the country’s 1.6 million AWCs.

Anganwadi children: paltry allocation

Among the other notable initiatives announced by finance minister Sitharaman in her budget speech are establishment of 50,000 Atal Tinkering Labs (ATLs) for government school children “over five years” without any specific allocation. However, 10,000 ATLs per year to enable children in government schools to learn by tinkering with lab and other equipment is a fleabite given that the total number of government schools countrywide is 1.10 million.

Likewise an airy promise is made that broadband connectivity will be provided to all government secondary schools and PHCs (primary health centres) without the budget papers disclosing any specific allocation for these high potential initiatives. In this connection, it is pertinent to note that according to UDISE+ 2023-24, 57.2 percent (837,900) and 53.9 percent (793,800) of schools are without computers and internet connectivity. Yet no specific allocation has been made in Budget 2025-26 to make good these deficiencies. Ditto, a Bharatiya Bhasha Pustak Scheme to provide digital-form Indian language books for schools and higher education is promised by the finance minister. But since no specific allocation is made, it is likely to be a pie-in-the-sky.

Narendar Pani: optimisation neglect

A project to set up five National Centres of Excellence in Artificial Intelligence announced last year for which Rs.110 crore was allocated, has been given an additional Rs.200 crore in 2025-26; an unspecified amount will be spent for augmenting infrastructure in 5 IITs started after 2014; 10,000 additional seats will be provided in medical colleges and hospitals. The budget minutae don’t disclose any specific provision for these projects. Presumably they will be funded out of allocations made for Digital India-learning (Rs.681 crore); Research & Innovation (Rs.327 crore). But given that these sums have to be shared by 45,000 colleges and 1,100 universities, they are too small to make significant impact. In this connection, it’s pertinent to bear in mind that 80-90 percent of allocation made for education is swallowed by revenue expenditure — administration expenses and salaries and pension, leaving little for capital expenditure.

In the circumstances, there is no escaping the reality that a determined resource mobilisation initiative led by the Central government which will stimulate state governments to do likewise, is urgently needed to rejuvenate run-down public education infrastructure — lavatories, laboratories, libraries, well-equipped digitally connected classrooms presided by well-trained teachers. The unimaginative, drab incremental budgeting practiced by finance minister Sitharaman is unlikely to serve the cause of bringing the world’s largest child and youth population to realise anywhere near its full potential as the ASER surveys and even NCERT’s NAS (National Achievement Survey) have confirmed year after year.

In this cause for the past decade, every year conterminously with presentation of the Union Budget, your editors have been presenting a schema/blueprint for the Union government to modestly reduce establishment expenses, middle class subsidies, grasp the nettle of privatisation and impose modest taxes to mobilise Rs.7-8 lakh crore for investment in augmenting and upgrading public education infrastructure. An updated edition of this schema is presented herewith (see p. 65).

This writer is of firm belief, if provided access to well-provisioned schools and higher education institutions with globally benchmarked libraries, laboratories, lavatories, and digitally connected classrooms, India’s eager-to-learn children with unique self and peer learning capabilities have inherent capability to create and apply new knowledge and invent globally acclaimed goods and services. And also record productivity increases that will pitch the perennially floundering Indian economy into a new higher growth orbit.

Renowned computer scientist and educational theorist Prof. Sugata Mitra’s revealing computer-in-the-wall experiment in a Kolkata slum (1999); the dazzling success of the Indian diaspora driven by enabling infrastructure, and emergence of several Indian cricket and other sports champions provided minimal training facilities, are ample proof that given access to half-decent nutrition and enabling infrastructure, India’s children and youth endowed with exceptional self and peer learning capabilities can conquer the world. Provided globally benchmarked education infrastructure and facilities, they have the capability to evolve into high productivity, globally competitive professionals in all fields of endeavour and walks of life. Therefore in the dawn of a new age of inventions and innovation powered by game-changing artificial intelligence and digital connectivity, there’s urgent need for a concerted national effort to develop the country’s abundant and high-potential human resource.

“Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman needs to be commended for persisting with her focus on hard infrastructure development, a force multiplier for economic growth. But hard infrastructure — roads, bridges, rail connectivity, energy and highways construction — needs to be supplemented by soft infrastructure — human resources — to optimise infrastructure capital expenditure. The downside of Budget 2025-26 is that to reduce the fiscal deficit, social welfare, i.e, human resource development outlays, have been slashed. At this juncture in the nation’s history, it may have been a more beneficial trade off to suffer a larger fiscal deficit to make greater provision for education and health,” says Dr. Narendar Pani, JRD Tata Chair Professor of Economics at the prestigious National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore (estb.1988).

A determined — even if belated — effort to develop India’s untapped human resource to optimise sustained investment made in hard infrastructure, is excellent advice. Although the capability of former and contemporary political leaders to dream big is commendable, it’s high time they and the establishment as a whole, became aware that big dreams such as Vishwaguru, Viksit Bharat and $30 trillion GDP by 2047, require to be built on the strong foundation of a well-educated, high productivity human resource base. Building this strong foundation necessitates urgent transformation — even at risk of excess — of India’s 1.47 million schools, 45,000 colleges and 1,100 universities into shining, show-piece institutions in which the world’s largest child and youth population is attracted to learn deeply and joyfully.

Union Budget 2025-26: Major allocations — I (Rs. crore)

Union Budget 2025-26: Major education allocations — II (Rs. crore)

Add comment