Some history professors in Florida are paying more attention these days to the future than to the past. The historians have organised themselves to promote the value of their discipline against a growing sentiment that history is “non-strategic” in an economy that needs more engineers, scientists, entrepreneurs and workers in the health professions.

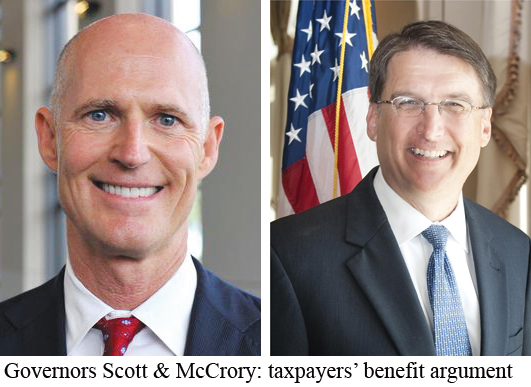

This is no longer just an academic issue. Like several other US politicians, Florida’s governor, Republican Rick Scott, has questioned whether taxpayers should continue fully subsidising public universities to teach subjects he says are in low demand. Academics in the humanities and some social sciences fear this threatens the survival of their departments.

“If I’m going to take money from a citizen to put into education, then I’m going to take that money to create jobs,” Scott told the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. “Is it a vital interest of the state to have more anthropologists? I don’t think so.”

Republican governors of North Carolina and Wisconsin have made similar pronouncements. “If you want to take gender studies that’s fine. Go to a private school and take it,” says North Carolina’s governor Patrick McCrory. “But I don’t want to subsidise that if that’s not going to get someone a job.”

This debate about the relative worth of sciences versus the humanities is not new. But it has been propelled by the escalating cost of higher education. As students fall deeper into debt to pay for their tuition, more than two-thirds now believe the goal of attending university is to increase their earning power, according to research by Arthur Levine, president emeritus of Teachers College, Columbia University.

About 88 percent of this year’s first-year undergraduates in the US say “getting a better job” is the top reason they enrolled, according to a survey by the University of California, Los Angeles’ Higher Education Research Institute (The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2012). In 2006, 71 percent gave that reason.

The debate has driven a wedge between conventional four-year universities and some two-year community colleges, which enroll about half of the nation’s post-secondary students and typically focus on vocational education. In response, several associations of universities with four-year courses are fighting back. The Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) is aggressively advocating the importance

These organisations contend that what employers really want from universities is not jobs training but graduates who can think critically, write and speak well, and solve problems. “(Employers) say, ‘I want an engineer who can talk to people. I want an engineer who can write a memo. I want an engineer who doesn’t act like a goof.’ Everybody rolls their eyes when (employers) do that, but the data says they’re right,’’ says Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

An AAC&U survey of corporate executives found that nearly 90 percent want workers with verbal and written communication skills, 75 percent are looking for graduates who understand ethical decision-making, and 70 percent say they need innovative and creative employees. “None of this is to (criticise) the disciplines of science and engineering and technology, but we also need to train people in the art of understanding the world around them, where they fit into society and those sorts of things,’’ says Norman Goda, a history professor at the University of Florida, who has helped to organise a petition against the governor’s proposal to charge lower fees for “strategic’’ majors in high workplace demand and more for “non-strategic’’ — largely humanities — majors such as history.