West Bengal: Sceptical jubilation

-Baishali Mukherjee (Kolkata)

With the daily count of Covid-19 cases in West Bengal dipping from 24,000 cases per day in mid-January to 500 on February 13, the state’s hyper cautious Trinamool Congress government announced reopening of all primary and upper primary schools with effect from February 16 — after a 23-months lockdown. The government also greenlighted restart of the state’s anganwadi centres established by the Central government under the Integrated Child Development Scheme (1976).

While there was initial jubilation in the state about schools opening after the unprecedented pandemic lockdown, educationists and educators are dismayed by the scale of the challenge confronting them. Media reports from all over Bengal confirm that a large number of students have dropped out of primary classess — especially of government schools — because they have started working. Reports also confirm that youngest children who have resumed classes have forgotten what they had learnt.

A year ago, an Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) survey indicated that the lockdown of schools had inflicted a huge learning loss to primary school students statewide. ASER field personnel tested primary children in 10,141 households in 510 villages of all districts of Bengal, except Darjeeling. Their report indicated that the reading and arithmetic competencies of children in government schools had reduced by 7-10 percent respectively and only 30 percent of class III children were able to read class II texts or do class II-level subtraction sums. It also highlighted that only one out of six students received learning material during the first eight months of the pandemic and only one-third had access to smartphones.

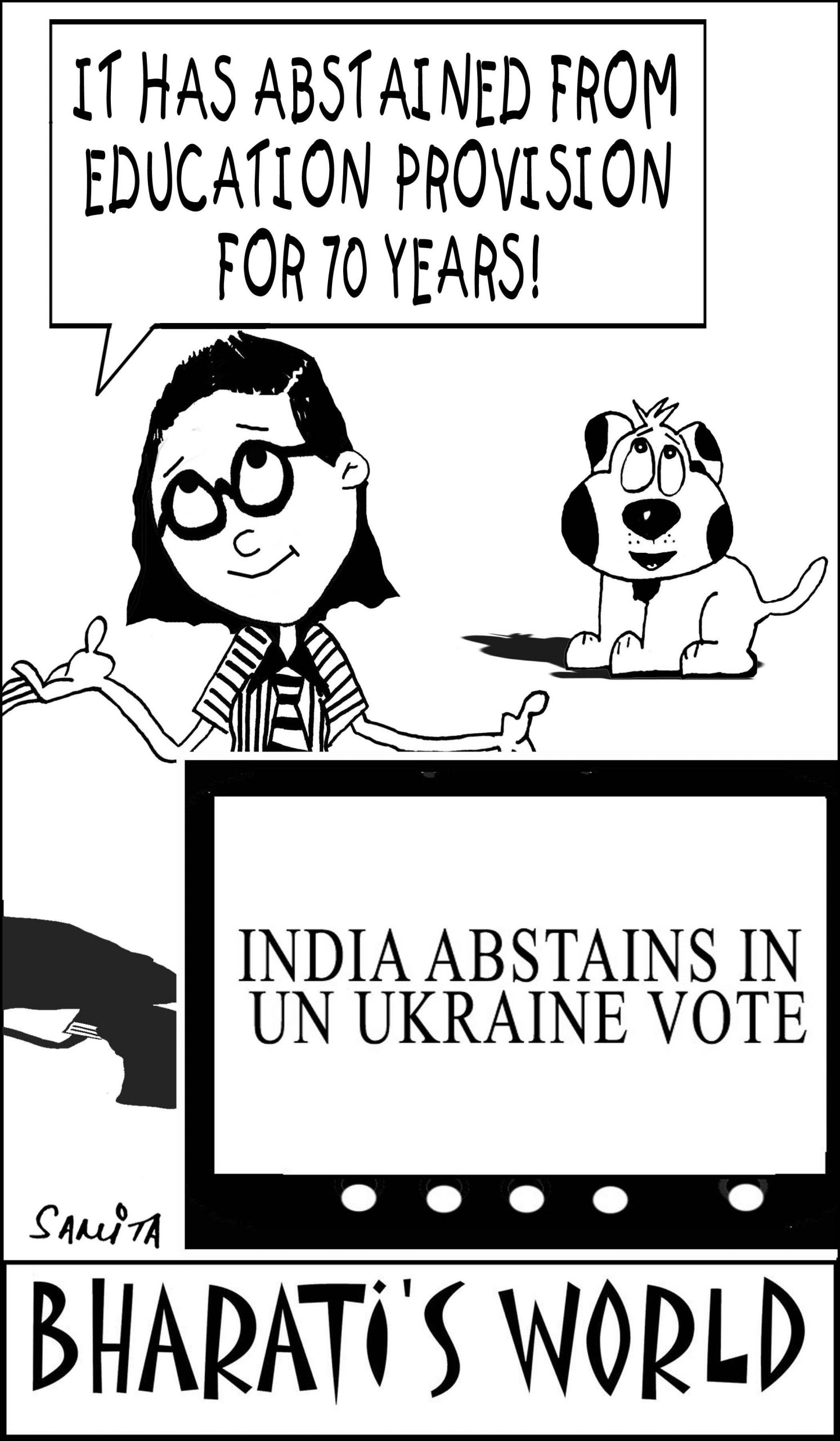

It is pertinent to note that if India’s education sector pandemic lockdown is the world’s longest (82 weeks), within India West Bengal’s is the longest among all states (99 weeks). Somewhat belatedly following reports of massive learning loss of children, parents, students, teachers’ organisations and students’ bodies of the state have begun to raise the volume of protest against exaggerated caution about restarting normal schooling.

With the latest ASER survey (2021) confirming these apprehensions, several intellectual heavyweights including Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee, Sukanta Chaudhuri, professor emeritus of Jadavpur University, and Achin Chakraborty, professor of economics and director of the Institute of Development Studies, Kolkata, have expressed deep concern about the future of West Bengal’s 8 million children enrolled in 65,000 primary schools.

Comments Abhijit Banerjee in The Times of India (February 10): “Teachers will have to play a crucial role in identifying the shortcomings of students and filling the learning gaps. We have to find a new approach to prevent the bond between students and schools from weakening. The focus should be on not leaving anyone behind because if we lose this opportunity, a generation will lose their future.”

Likewise in a recent op-ed essay in the Anandabazar Patrika, Prof. Sukanta Chaudhuri, wrote: “In West Bengal, about 16 lakh children are admitted to primary school every year. The children of the last two batches did not go to school for a single day. There is a strong possibility that more than half a crore (5 million) children in Bengal will remain completely illiterate. And with a large number of children growing up without learning to read and write, we are heading towards a catastrophe that will not spare any of us.”

Moreover, writing in The Times of India (February 10), Rukmini Banerji, CEO of the Pratham Education Foundation which publishes the annual ASER surveys wrote: “The immediate goals for primary schools are very clear. Getting youngest children ‘ready for schooling and learning’ and helping older children to ‘catch up’ should be the only two priorities for education in Bengal in 2022.”

Compelled to react, the West Bengal school education department announced that a bridge course of 100 days will be introduced from the very first day for students of all classes to fill learning gaps of the pandemic.

However, with the state’s TMC government having shirked its legal and constitutional obligation to provide free and compulsory education to all children for almost two years, West Bengal’s academia and bhadralok (refined middle class) remain sceptical about the implementation of the bridge course across 92,000 government schools in Bengal. Now all eyes are on the state’s budget, to be tabled on March 8, in the hope that substantially greater provision will be made for West Bengal’s cruelly short-changed children.

Add comment